Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

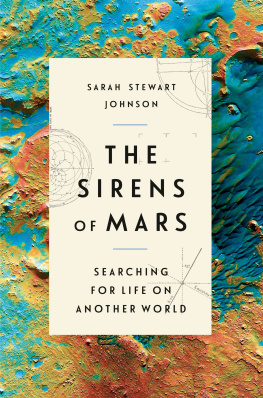

Copyright 2020 by Sarah Stewart Johnson

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

C ROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Title-page image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State University

Part-title image: Illustration from Scientific American, August 20, 1892, Professor Pickerings Observation of Mars

Chapter-opening image: Morphart Creation/Shutterstock

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Johnson, Sarah Stewart, author.

Title: The sirens of Mars / Sarah Stewart Johnson.

Description: New York : Crown [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020007280 (print) | LCCN 2020007281 (ebook) | ISBN 9781101904817 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781101904824 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Life on other planets. | Mars (Planet)

Classification: LCC QB641 .J64 2020 (print) | LCC QB641 (ebook) | DDC 576.8/39099923dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007280

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007281

Ebook ISBN9781101904824

randomhousebooks.com

Cover design: Elena Giavaldi

Cover images: Sand dunes lie next to a hill within an unnamed crater in eastern Arabia on Mars. This false-color mosaic, in which bluish tints indicate fine sand and reddish tints indicate outcrops of rock, was made from images taken at visible and infrared wavelengths by the Thermal Emission Imaging System on NASAs 2001 Mars Odyssey mission. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU); Fol 36-37 Astronomia nova Aitiologetos, by Johannes Kepler (engraving), Bridgeman Images (top right); August 20, 1982, Professor Pickerings Observation of Mars, Scientific American (center left); Morphart Creation/Shutterstock (bottom right)

ep_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

Contents

E VEN WITH THE miracle of modern travel, it takes days for me to reach the edge of the Nullarbor Plain: three or four flights, a quick shower in Perth, then a night or two backtracking east in a rented truck. The two-lane carriageway stretches endlessly through the ghost towns of Australias old goldfields. Eventually I turn onto dirt roads, onto red rock. When I stop the truck and climb down from the cab, everything is still. Finally, Ive arrived at the place where the desert cracks open.

I come here every couple of years, to the ancient terrain of the Yilgarn Craton, some of our worlds oldest rocks. Dotted throughout the dark ochre expanse are oval ponds that are as corrosive as battery acid. Yet in these sulfuric waters, against all odds, is the most astonishing array of life. I come to investigate how primitive microbes survive the harsh conditions, how they harvest energy, and what traces they leave behind in the minerals. I come because Im a planetary scientist and because this is one of the most similar places on Earth to the ancient surface of Mars. I come to the Yilgarn and other wild wastelandslike the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica, like the Atacama in Chileto hone my skills at finding life.

Out in the desert, I rise with the dawn. I pull on my tattered field clothes and slather sunscreen across my face. My boots crack with salt as I slip my feet into them. I throw on my hat, with wine corks hung from string around its brim, ready to drive away the flies. I weigh my pack down with equipment and water and head straight onto the flats. I spend my days wading into the sucking mud. In some places the ground parts easily. In others, the enveloping salts are as hard as ice. I note the GPS coordinates, map the terrain, measure the water chemistry, and assess the minerals. Later, back in my laboratory, I will examine each tiny piece of the acid-encrusted world I place into a vial. The sun beats down. The wind whips around me. But I rarely notice. Im focused, consumed.

At the end of my workdays, after I load up my instruments, I climb up on top of the dusty cab, exhausted. As the sun begins to set, and the sky turns salmon pink, and red dust hangs in the air, its not hard to imagine that Im on another planet altogether. Staring off into the silence, I think of all my predecessors, some sitting in deserts just like this, some hoping to signal Mars with giant trenches of fire, others building enormous telescopes in the stock-still air. A boy curled up in the shadow of a Benedictine abbey, longing for his own corner of the unknown to map. A shutterbug from Indiana who developed tens of thousands of blurry images of Mars, hoping one might show something. A French aeronaut who piloted a helium balloon high into the stratosphere, so high that he might asphyxiate, just to get his measurements.

Its a peculiar band Ive joined, this pack of Mars scientists, fiercely bound across the generations by the enigma of a neighboring world. One might fairly wonder why we have pinned our hopes for finding life to this red planet. For the last couple of billion years, there has been no rain there. There are no rivers, no lakes, no oceans. Without the driving force of fluid erosion, scars left over millions of years by meteorites are strewn across the surface. Mars has no plate tectonics, no magnetic field, and little protective atmosphere. The terrain is quiet, exposed, and bewilderingly empty.

Yet long ago, before it rusted over, Mars was much more like Earth: smaller, but similar in size and elemental composition. In its early days, Mars was black with igneous rock. Untold piles of lava built the planets massive volcanic provinces, which bulged with enough basalt to flex the crust. The planets swollen side cracked opened as Mars cooled, with a fissure so deep that the Grand Canyon could disappear into a side channel. One of the largest mountains in the solar system was formed, towering over an escarpment that itself is nearly as tall as Everest.

Those volcanoes lifted greenhouse gases into the air, wrapping the surface with a blanket of atmosphere. We know from the geologic record that the terrain was warm and wet, at least periodically. Around the time life may have been getting started hereconceivably in volcanic pools, in Darwins warm little pondswater was present on Mars, pregnant with possibility. In fact, there may have been enough water to fill a northern ocean, still and deep, with a seafloor as smooth and flat as the abyssal plains of the great Pacific.

Then, between three and a half and four billion years ago, our planetary paths diverged, and Mars was laid bare. Almost all of the atmosphere disappeared, and so did the water. The planet slipped into a deep freeze, colder than the cold of Antarctica, leaving Mars the hyper-arid, frozen desert we know today, bathed in high-energy solar and cosmic radiation. Now a dust the consistency of red flour coats the surface, lofted by dust devils into the impossibly thin air.

Yet life, we have learned, is stunningly resilient. It can adapt, it can wedge into a crevasse, it can hang on against all odds, and it can reveal itself in unlikely ways. Traces of biology hide in the most unexpected locations. Its why I roam the terrain at the edge of the world, hunting for the subtlest fingerprints of life, learning how to look.