For the Tree of Life Synagogue, which has become a living tribute to the strength, resilience, and beauty of the Jewish people.

Contents

No amount of fire or freshness can challenge what a man will store up in his ghostly heart.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, THE GREAT GATSBY

Prologue

Y ou from Pittsburgh?

He wasnt expecting a question. He stood in the morning shadow of Epiphany Church with a cardboard sign that said something about being down-and-out and a dog. His head was down, his hair was matted.

Excuse me, I said again. You from Pittsburgh?

His eyes, slightly glazed, met mine.

Yep. Born and raised! he said, smiling. His big teeth made me blink; I wondered when the Osmonds started designing dentures and whether Catholic Charities got them in bulk.

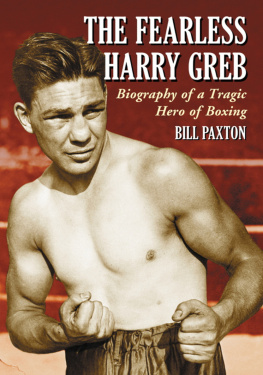

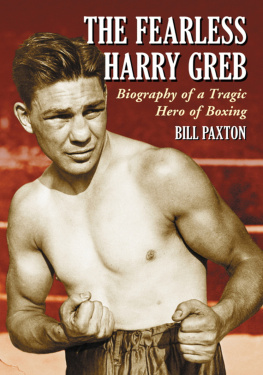

Have you ever heard of Harry Greb? I said.

Who?

Harry Greb. Born and raised over in the Garfield district. Middleweight king in the 1920s.

No, no Ive never heard of him. Was he better than Joe Louis? He wasnt better than Joe Louis.

Yeah he was. My names Springs. Whats yours?

Joe.

Aha!

I was getting ready to tell him that Greb was better than them all, that Grebs idea of a good time was beating up on heavyweights, that Greb fought three hundred times from 1913 to 1926, but Mass was about to begin.

Greb was married right here in this church a hundred years ago, I said on the way in.

You dont say.

This Side of Paradise

H e was late.

The ceremony, a Solemn High Mass at Grebs insistence, was set for 9:00 a.m. on January 30, 1919. Grebs manager, James Red Mason, had somehow convinced the couple to disregard a folk rhyme popular at the time and push the date up from Monday (married on Monday, married for health) to Thursday (married on Thursday, married for losses) . Pittsburgh itself was invited. Many of the thousand plus who attended were milling outside the church at 9:15, checking pocket watches and craning their necks on Washington Place. It was nearly 9:30 when taxis rumbled up and screeched to a stop.

A door clacked open as the crowd filed into the church and when the leg of the bride-to-be swung out to the running board, a few at the back sneaked a peek. Next came an arm and a gloveless hand as eighteen-year-old Mildred Kathleen Reilly was assisted out and onto the street, a wide-brimmed hat pulled low in the fashion of the day. She wore a dark blue travelling suit and lipstick like Clara Bowstill something of a scandal as the Jazz Age dawned.

On her finger was a diamond. A karat and a half, set on a platinum band. It sparkled like some low-hanging star plucked from the sky.

Nearby was her mother. She knew that Mildred would have done exactly that, if she could, reach up through the smoke and the sprawl of Pittsburgh and pluck a star if it caught her eye. Shed tweak the thumb of the angel who held it too. Mrs. Reilly knew better than anyone that her eldest daughter was a willful girl.

Did she wonder at her that morning? She may have been in a swoon of relief. After all, only three years had passed since Mildred disappeared from home, missed her fifteenth birthday, and scared her half to death. It was a Tuesday in August when she told her mother that she was off to find work at a varnish company. It was a likely story. Her birthday was Wednesday and on Thursday Police Seek Missing Girl appeared in the Daily Post .

Nine days later, Mildred appeared in an aldermans office filing a suit to recover salary owed for her appearance in a film promoting the citys Be-Brite clean-up campaign. When asked her name and address, she was truthful. When asked her age, she was not. Twenty, she said.

Mildred dreamed of being an actress. She appeared in amateur shows at the Nixon Theater on Sixth Avenue and likely a few others downtown before Mrs. Reilly found out and put her foot down. No daughter of mine! It echoes faintly down through the decades. The pandemonium a willful girl can bring to the home does too: the screaming and slamming doors, the sobbing in the room, younger siblings wide-eyed and silent; the Irish mother, worn and haggard at thirty-seven, but with eyes afire and a brogue turned stern. There was no Mr. Reilly to lean on, to turn to when things got bad. Mildred was seven when he died from a perforation of the bowel in Indiana where he found a job as a railroad brakeman. He was always looking for a way up. Mildred was looking for a way out.

In December 1915, the Pittsburgh Sun ran an article written by that eras Miley Cyrus that began with the headline Anita Stewart Tells Girls How to Achieve Success and Happiness. Framed as a heart-to-heart talk to girls, it began by undermining mothers: How can the mother who knows only the problems of her own home be a guide to her daughter who is living the life of a stage actress?

The day the article appeared on newsstands, Mildred went to a pharmacy and bought a bottle of blue triloidspoison. At midnight, she took the cork out and crushed and scattered four tablets on the floor by her bed. Then she rubbed one on those Clara Bow lips to make them blister.

Mother! Mother! she screamed. I have taken poison!

An aunt and uncle living on nearby Meyran Avenue got involved and the police were called. As the officers administered first aid, they told her she was being taken to the hospital, and Mildred, realizing shed gone too far this time, blurted out that the whole thing was just a stunt. No one believed her.

At the Homeopathic Hospital, doctors stuck hypodermic needles into her armthat was fierce, she told a reporterand kept her under close watch for symptoms that never appeared.

Her stunt worked. By January 1917, she was working at the Victoria, a new burlesque house at 956 Liberty Avenue, around the corner from the Nixon. She had a specialty act that could have been a bawdy song, a racy (though not nude) dance, or a comedy sketch. It was evidently well received because by March she had a supporting role in a burletta called Hotel Uproar that featured a night clerk causing indescribable confusion among guests and proved a scream from beginning to end.

Was Mrs. Reilly in the audience? Almost certainly not. But someone else almost certainly was.

Harry Greb emerged from the idling taxi wearing a fur-collared coat over a fashionable suit, his dark hair slicked back and the sides of his head shaved clean. A reporter made a note about his natty appearance in the role of groom.

He was a nervous wreck.

Born June 6, 1894 to a stone mason of severe character from Germany and a mother with roots in Prussia and Bavaria, Greb grew up in a household where schnitzel and sauerkraut were staples, where hard work and good manners were expected and Deutsch was spoken.

He was baptized Eduard Henry on June 10 at St. Josephs, a German-Catholic parish in the Bloomfield neighborhood of Pittsburgh where he attended school and received the sacraments. Only later did he adopt the name Harry after a baby brother who died in the crib. Six children were born to Pius and Anna, of whom four survived into adulthood. Greb was the eldest with three sisters behind him.