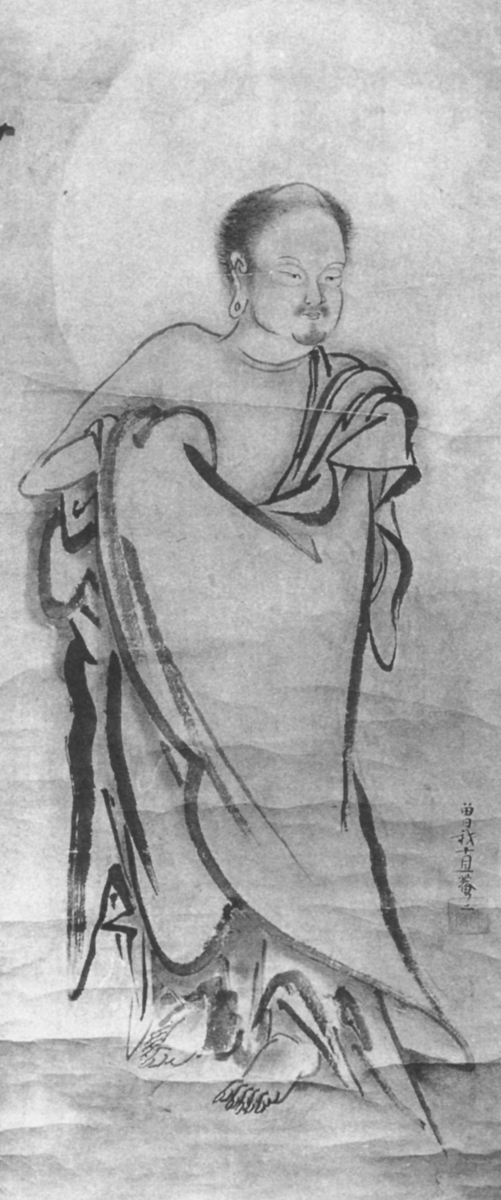

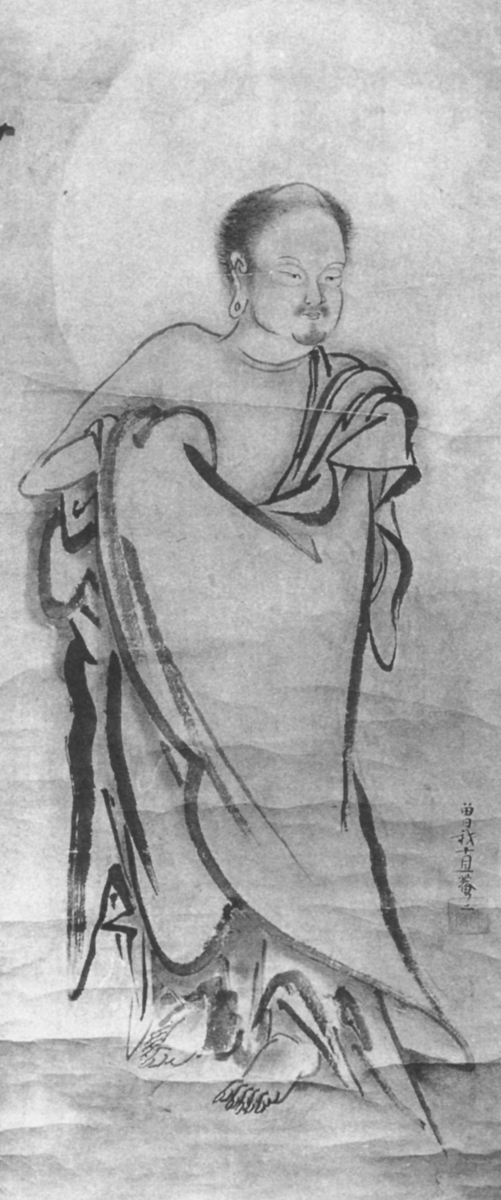

Shussan Shaka by Soga Nichokuan. Detail. Shmyji. Kyoto.

Poems of the Five Mountains

An Introduction to the Literature of the Zen Monasteries

Marian Ury

Second, Revised Edition

Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies, Number 10

Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1992

Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program.

1992 by the Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 108 Lane Hall, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1290

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Ury, Marian

Poems of the five mountains : an introduction to the literature of the Zen monasteries / by Marian Ury. Rev. 2nd ed.

p. cm. (Michigan monograph series in Japanese studies ; no. 10)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-939512-53-X (alk. paper)

1. Chinese poetry Japan Translations into English. 2. Zen poetry, Chinese Japan Translations into English. I. Title. II. Series.

PL 3054.5.E5U78 1992

895.114408dc20

91-32839

CIP

Typeset by Sans Serif, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

Printed and bound by Braun-Brumfield, Inc.

A Note on the Type

This book is set in Garamond type. Jean Jannon designed it in 1615, but credit was mistakenly given to Claude Garamond (ca. 1480-1561), an early typeface designer and punch cutter, probably because it resembles his work in refining early roman fonts. It is an Old Style typeface, a group of typefaces first developed for printing and characterized by their small x-height and oblique stress.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1984 (Permanence of Paper).

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-939512-53-9 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-472-03837-4 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12815-0 (ebook)

ISBN 978-0-472-90215-6 (open access)

The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

For Louis S. Bloom, 1896-1970 and Edith Lapin Bloom, 1899-1989

Contents

In the preface to the second edition of his Seven Types of Ambiguity, the poet and critic William Empson cites Sir Max Beerbohm's fine reflection on revising one of his early works; he said he tried to remember how angry he would have been when he wrote it if an elderly pedant had made corrections, and how certain he would have felt that the man was wrong. I am not I hope a pedant at any age. On the contrary, I find myself rather less interested than I used to be in the kind of research that generates little notes about this and that, and a great deal less interested in imposing such notes on readers. I have nevertheless followed Empson's example in attempting, so far as possible, to respect the work of that earlier version of myself who produced this book; she was a better poet that I suspect I would be now, and she knew more about Zen. A very few, very minor, revisions have been made in the poems, and a page of notes has been eliminated. I have updated one or two Western-language bibliographical references. It has unfortunately not been possible to reproduce the numerous illustrations in color of the monk-poets' calligraphy that Eric Sackheim, the original publisher of the book under the Mushinsha imprint, provided for it and that were one (and perhaps the least) of the many reasons that I will always feel indebted to him. In other respects, however, the book is essentially unchanged.

I am glad to repeat the acknowledgments that appeared in the original edition. First, to the Asian Literature Program of the Asia Society under a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and to the Director of the Program, Bonnie R. Crown; even now, many years later, I continue to regret the discontinuance of this program, which offered material help and encouragement to many translators. Also to Junnko T. Haverlick, David Olmsted, Delbert True, Hans Ury, and Benjamin Wallacker for various kindnesses; as well as to Cyril Birch and Burton Watson, who offered helpful suggestions and corrections on portions of the manuscript. And I should like to add to this list Bruce E. Willoughby and the University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies.

I would be remiss if I did not add that, although my introduction speaks of this book as only a beginning, the reader who is interested in continuing with the subject now has additional English-language sources to turn to. David Pollack's Zen Poems of the Five Mountains (New York: Crossroad; and Decatur, GA: Scholars Press, 1985) presents translations from a broader group of poets, the individual poems arranged and annotated to delineate the various aspects of the monks' lives and to emphasize their religious practices. A selection of gozan poems, translated by Burton Watson, can also be found in From the Country of Eight Islands, edited and translated by Hiroaki Sato and Burton Watson (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981). Both volumes can be warmly recommended.

Marian Ury

June 1991

The poems in this book were written in Chinese, in the classic shih form. Their authors were Japanese Zen monks whose lives together span the years from 1278 to 1429, for Japan a time of turmoil but also of growth. Although ten of these sixteen men visited China, all were born and died in Japan: for all, Chinese was an acquired tongue. Most of their very many poems, and for that reason most of the poems translated here, are on subjects that have little directly to do with religion. A Buddhist monastery is a place that by its very existence magically enhances the welfare of the state; it is a place where the individual is aided to strive for enlightenment; it is simultaneously a place where men live together hierarchically in order that they may live harmoniously a place therefore where restraint, obedience, and not least courtesy must govern the relationships among the inhabitants. Verse written in Chinese had been a medium for exchange of courtesies between men of education since education began in Japan. In secular society poems and couplets in Chinese were exchanged between friends, produced impromptu (or otherwise) at banquets, made into song-texts, used to brighten festivities and solemnize mourning. The microcosm of the Zen monastery likewise produced many occasions that called for the composition of Chinese poems: there were promotions and leave-takings, visits from friends and dignitaries of both the religious and secular spheres, sickbeds, celebrations, and anniversaries. There were filial relationships to be attended to, for the disciple by virtue of his intuition of enlightenment is accepted by his master as son and heir; his fellow disciples become his brothers, his master's teachers his ancestors, the lineage of his school the focus of his loyalty. All deserving to be honored in verse, along with such universal subjects as sorrow, old age, homesickness, and the beauty of landscapes and seasons.

The genre to which the poems in this book belong is called gozan bungaku. Bungaku means literature; gozan means five mountains. In China and Japan monasteries were so often situated in the mountains that a mountain became synonymous with the monastery located there. Five refers not to the number of the Zen monasteries themselves but to the number of ranks in the system by which the major ones were ruled under government patronage. This system, modeled after one that existed in China under the Southern Sung, seems to have come formally into being in Japan at the beginning of the fourteenth century.