The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

One recent afternoon, I padded upstairs to my bedroom, dug up some legal weed I had stashed in a drawer, and got stoned. It was just after lunch, usually the most productive part of my workday, and the late summer sun illuminated my midday indulgence in clear, withering light. Back in my basement office ten minutes later, I donned my fancy Bose headphones (noise-canceling, consciousness-consuming, sonically perfected to some canine ear degree) and crawled under my desk to escape all other stimuli. I had important work to do. I clicked the Play button on my iTunes, lay down on the floor, and closed my eyes, preparing to hearI mean really hearVan Dyke Parkss 1967 album, Song Cycle, for the first time.

Full disclosure: Ive owned a copy of Song Cycle for at least twenty years and have listened to it, or tried to, dozens of times. I had known the records legend for probably twenty years before I bought it, and had come to admire the music in its grooves even as I found it inscrutable andhow can I put this?an experience that was something other than fun. And I like eccentric art. But Song Cycle threw me off time after time. It requires your full attention and a willingness to open your ears and your mind, cut loose every expectation of popular music you might possess and let it take you over.

So, I went under my desk. No one else was in the house. The lights were dark, and so was my cell phone. Cut off, I willed the modern world away: the Twitter rage, the sanctity of shareholder value, the desiccated dreams, the institutionalized fuckery, the fact that everything is worse than its ever beenbut when has that not been true?

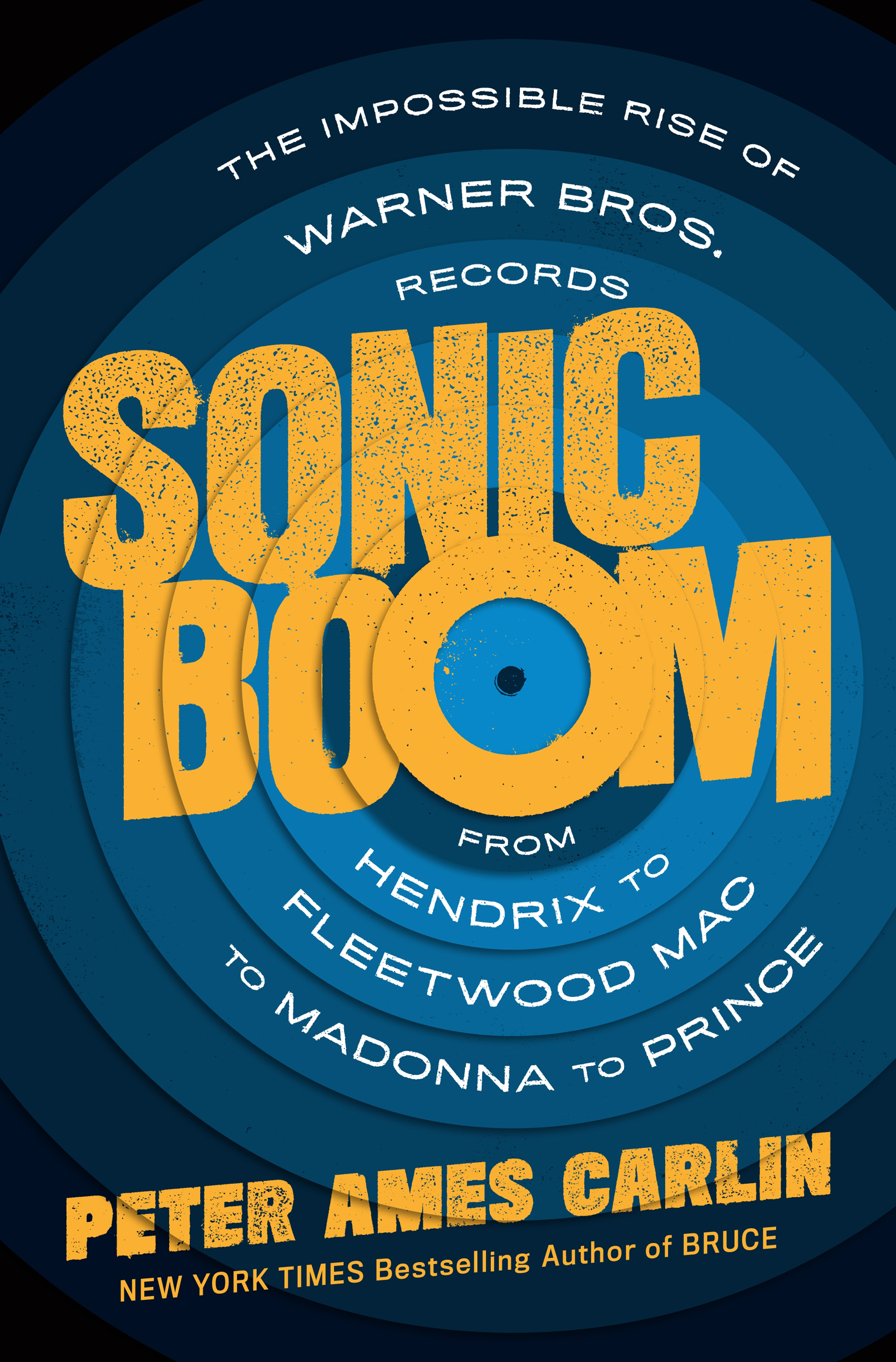

In 1967, Van Dyke Parks, a twenty-four-year-old classically trained composer and pianist with his antennae tuned to the avant-most edge of the garde, came to his latest opportunity with wild ambitions. Given a multi-album contract with Warner Bros. Records (WBR), a deal that came with a big recording budget, creative control, and no deadline, Parks composed songs for an original album that would marry his intricately orchestrated music with Delphic lyrics invoking the dreams and disasters of Americas past while also opening new horizons for musical and spiritual exploration. Like the Beatles in-progress pop art masterpiece, Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band, and the Beach Boys unfinished psychedelic/symphonic Smile, on which Parks had served as Brian Wilsons collaborator in 1966, Parkss debut album would create its own curiously sparkling world. As Parks and his twenty-five-year-old WBR staff producer Lenny Waronker agreed, they would enter the studio each morning with no guidelines or boundaries. If Parks heard a sound in his head, he and Waronker would work for however long it took, using whatever tools they had or could invent, to capture it on tape.

None of this was normalnot in the popular music business of the mid-1960s, anyway. In 1967, when the top five singles of the year were, in descending order, Lulus old-school pop hit To Sir with Love, the Box Tops straight-rocking The Letter, Bobbie Gentrys gothic country ballad Ode to Billie Joe, the Associations romantic Windy, and the Monkees pop-rock Im a Believer, the vast majority of pop songs could still be recorded, from basic track to vocals to overdubs, before lunch. But thats not what Parks and Waronker intended to do, and it wasnt what the visionary executive reinventing their record company wanted.

After I hit Play, I had time for a deep breath before the rising sound of a bluegrass band filled the emptiness: banjos, strummed guitars, a slide guitar, a string bass, and voices, all clattering through Black Jack Davy, an ancient American folk song about a scalawag who seduces a proper lady into abandoning her family and taking up with him. The rattletrap fades in fifty seconds, revealing a song within another song. This is Vine Street, an original tune Parks commissioned from fellow composer, pianist, and newly signed Warner Bros. artist Randy Newman. The scratchy opening vignette blooms into a string quartet and the winsome voice of Parks, as he describes what weve just heard: a tape of his old band, a folk combo of no repute whose members have long since vanished from his life.

Parkss strings leap and tumble, speeding up and slowing down, alluding to eighteenth-century Europe, nineteenth-century ragtime, and the sentimental movie soundtracks of twentieth-century Hollywood, that never-never land where dreams are still born.

Or is that stillborn?

Hmm.

And here comes more, more, more: String sections collide with electronic keyboards, which keep their distance from the Russian violins and balalaikas. Steam locomotives rumble west in one song and then chug eastward through another. There are birds and single-cylinder motors; the dying blast of the Titanics basso magnifico horn; then a tattered verse of Nearer My God to Thee, artificially Dopplered to portray our movement past the doomed vessel. There are harps, chattering locust percussion, and electronic distortions of Parkss wispy vocals, his words and melodies cloaked in gossamer and subjected to the cardboard tape-yawing device he and Waronker jury-rigged onto the recorders spindle and dubbed the Farkle. Also, they sped up almost every song. I used to speed up everything, Waronker says. I was taking so much speed back then it just sounded better that way.

Parks was just as keen on high-velocity consciousness, and sometimes the fellows would get so pilled up theyd have to run around the block to calm themselves down between takes. But even when they were high, they were not sloppy. Parks was one of the rare hippie musicians who brought unerring discipline to his galactic explorations. His lyricsmulti-entendred musings on life, liberty, and the inevitability of death and failureare Joycean in their linguistic invention and their Farkled perspective of America and the outer limits of physical and metaphysical existence.

Song Cycle clocks in at less than thirty-three minutes, but its such complicated listening that it can feel like hours. Just try to track the quirky harmonics written into the string charts or all the colliding time signatures, or the way a steam whistle cry jumps off the horn sections melody in the middle of The All Golden and is then quickly resolved by the horns next note. Can you tell if the operatic shriek at the start of By the People belongs to a trained soprano or to a theremin wailing through the top of its range? I cant. Then come the church bells and claps of thunder and a fiddle that is part front porch sing-along, part German surrealist horror movie. Strike up the band brother, hand me another bowl of your soul, Parks and his chorus chirp amid the bells and the light drumming of a rainstorm. We now are near to the end / If you stay with the show say we all had to go