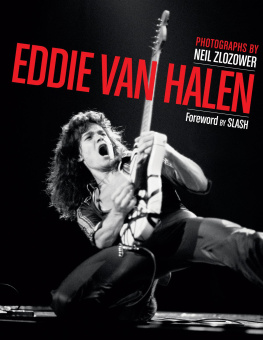

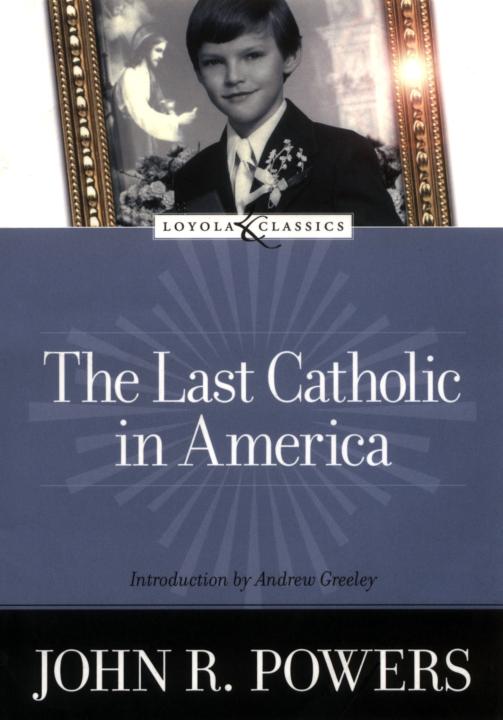

The Last Catholic inAmerica

Books in the Loyola Classics Series

Amy Welborn, general editor

The Devil's Advocate

by Morris L. West

Do Black Patent Leather Shoes Really Reflect Up?

by John R. Powers

The Edge of Sadness

by Edwin O'Connor

Helena

by Evelyn Waugh

In This House of Brede

by Rumer Godden

The Last Catholic in America

by John R. Powers

Mr. Blue

by Myles Connolly

Saint Francis

by Nikos Kazantzakis

Vipers' Tangle

by Francois Mauriac

The Last Catholic

inAmerica

JOHN R. POWERS

Introduction byAndrew Greeley

vii

Introduction

The invitation to write an introduction for a new edition of John R. Powers's The Last Catholic in America, to be included in a series of "classics" astonished me. How long did it take for a Catholic novel to become a classic? Dr. Powers had written the book only a couple of years ago, had he not? My astonishment turned to dismay when I saw the 1973 copyright datemore than enough time to become a classic!

I devoured the book again just as I had more than thirty years ago, enjoying it just as much as I had then, perhaps even more. Back in 1973, it was one of the first of the now extensive literature of Catholic nostalgia, which includes memoirs, fiction, and drama. The Last Catholic in America paved the way for the rest and is, far and away, the most humane of the lot.

Powers's novels are indeed nostalgic. They are also wise, hilarious, biting, and observant. They are fine examples of the coming-of-age tale, written with a pitch-perfect balance between the innocence of the child and the bittersweet knowledge of the adult. For beyond our relief at getting beyond all of what we laugh at, sometimes incredulously, haunts a suspicion that something meaningful has been lost. That's where the nostalgia enters-for the pains and joys of Catholic life before the Second Vatican Council.

What's amazing is that The Last Catholic in America was published less than ten years after the close of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), the massive gathering of all Roman Catholic bishops convened by Pope John XXIII, and that ten years made all the difference-to the world of Eddie Ryan, that is. For no doubt, if St. Bastion's were a real parish, and you'd gone there in 1973, you'd find a far different place than Eddie Ryan knew in the 1950s or even in 1965. There'd be no Latin Masses; the nuns who were left would have changed their long habits for something more practical; the Baltimore Catechism and its neat formulas would be just a memory. The priests still would have power to wield, but the laity would have a great deal more say about it than the hapless "Concerned Parents for a Better St. Bastion's Parish" who go to war with the pastor over the eviction of Garbage Lady Annie from property next to the new church (they're for it; he's against it).

Eddie Ryan couldn't have seen it. Father O'Reilly couldn't have seen it. Even Sister Eleanor, who could see you even when she was out of the classroom, couldn't have foretold the massive changes that occurred in the wake of the Council, some intentionally, others as unintended consequences.

That's the reason for the nostalgia that made this novel and its sequels (Do Black Patent Leather Shoes Really Reflect Up? in 1975 and The Unoriginal Sinner and the Ice-Cream God in 1977) so popular when they were first published. The people who read them knew Eddie Ryan's world. Like him, they'd left a lot of it behind, but also like him, they sometimes wondered if they'd left too much.

I have a special interest in The Last Catholic in America because it's about my neighborhood. I am West Side Irish but during the time about which Powers writes, I was living in exile on the South Side in a parish close to the parish of John Powers's childhood. I knew the territory. I had to fight off invaders from "St. Bastion" who tried repeatedly to crash our high club "dances" (at which no one danced until the very end of the evening). I even knew the Swank Roller Rink, which John Powers has immortalized. If anything, his description of what went on at the Swank is restrained.

The teens in my parish insisted that we must go there one night, even though I couldn't skate. So a few hundred of us showed up along with some innocent adult chaperones. Newly ordained priest that I was, I could hardly claim adult status. I think only two of our mob had to be taken over to Little Company of Mary Hospital with injuries. Maybe it was three. We never went again. I've often wondered whether John Powers was there that night or whether perhaps he might have been among the Friday evening raiding parties from "Seven Holy Tombs." He denies it. But then of course he would!

So I know the culture and the neighborhood of which he writes. It is South Side Chicago Irish in the middle of the twentieth century, a generation after James Farrell's Studs Lonigan and a generation before the sexua-abuse crisis. Powers is gentler and wittier than Farrell, and not nearly so angry. Both Farrell and Powers understand the power and the poignancy of love on the far outer edge of adolescence, although Powers sees more comedy in the dance than Farrell did.

Much of the Catholic world they both portrayed is gone now, caught up in the structural changes that came in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, which were, as I believe, fully intended by the Holy Spirit. The world may have changed, but the pains of early adolescence are still the same and probably always will be. Many of the Catholic schools in the neighborhood continue to exist. No one gets beat up anymore by the nuns; alas, there are not many nuns left. Yet the schools remain not only excellent educational institutions, but also places where human dignity is recognized and nurtured.

Whatever the new Catholic Church will look like in the years ahead, there will still be Catholic schools, which will continue to cope firmly and affectionately with those in the early years of adolescence. I suspect that eighth graders in such schools will read Powers and Farrell and marvel about how different things were in the old days-and how similar, even if there are no longer such temples of recreation as the Swank.

Years ago-maybe ten, maybe twenty-I led a crew of exteenagers to the Summit Theater in Chicago to attend the play based on Do Black Patent Leather Shoes Really Reflect Up? In the first act, the second graders sang "Bring Flowers of the Rarest" for their May Crowning. The whole audience-I almost said "congregation"-joined in the refrain "0 Mary we crown thee with blossoms today."