Chase Mark - The Little Book of Orchids

Here you can read online Chase Mark - The Little Book of Orchids full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Ivy Press, The, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

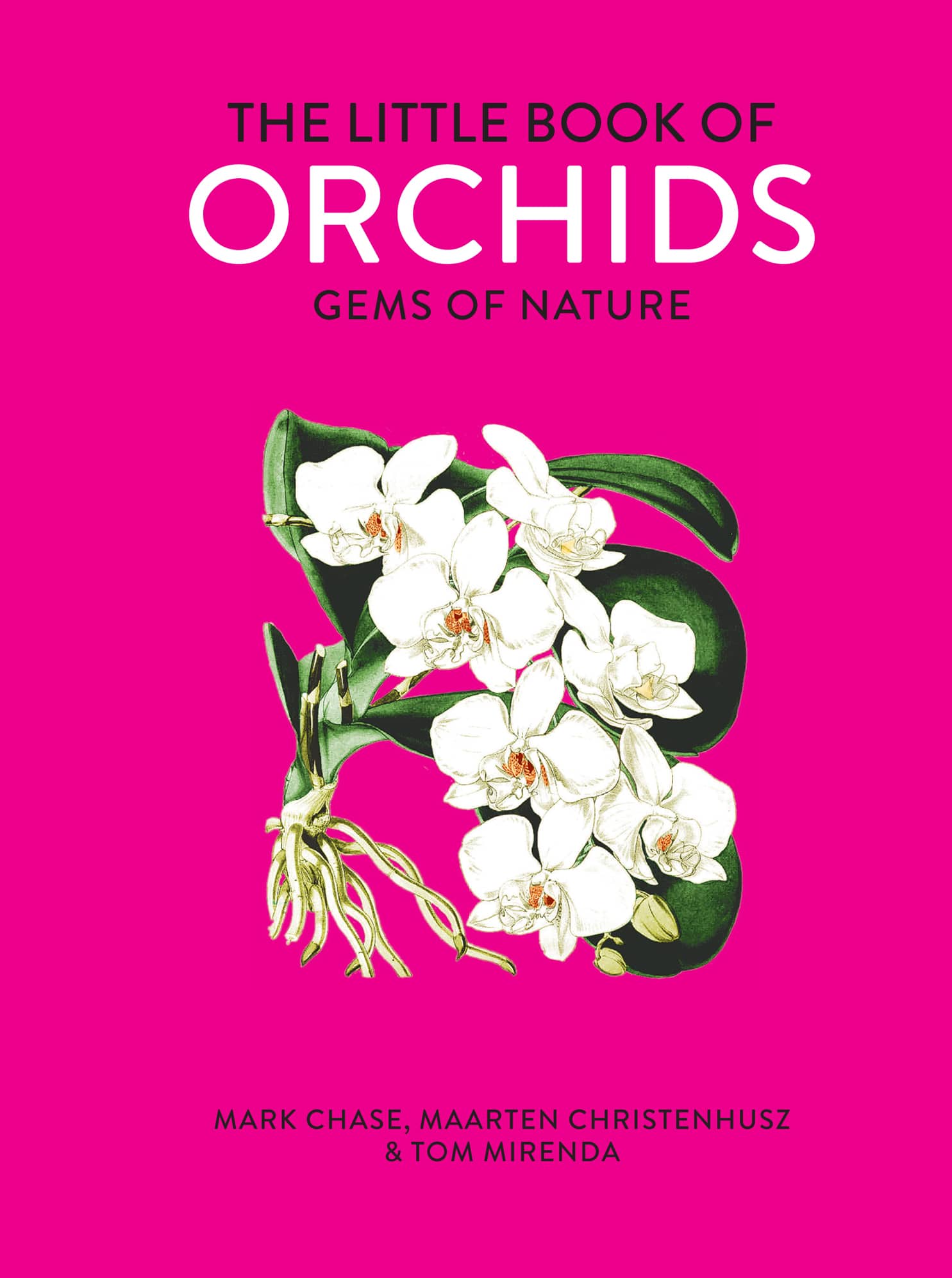

- Book:The Little Book of Orchids

- Author:

- Publisher:Ivy Press, The

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Little Book of Orchids: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Little Book of Orchids" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Little Book of Orchids — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Little Book of Orchids" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Mark Chase is a senior research scientist at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He co-edited Genera Orchidacearum and has contributed to more than 500 publications on plant science.

Maarten Christenhusz is a botanist who has worked for the Finnish Museum of Natural History and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He is deputy editor of the Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society.

Tom Mirenda is the Director of Horticulture, Education, and Outreach at the Hawaii Tropical Botanic Garden and the former Orchid Collection Specialist at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. He frequently lectures on orchid ecology and conservation in the US and abroad, and is a columnist for Orchids, the magazine of the American Orchid Society.

THE LITTLE BOOK OF

GEMS OF NATURE

MARK CHASE, MAARTEN CHRISTENHUSZ & TOM MIRENDA

Unquestionably lovely, orchids are far beyond being just beautiful. They are seemingly endless in their diversity, perpetually compelling, and astonishingly well adapted to a mind-boggling array of ecological niches and evolutionary partners. A geologically old family, members of the Orchidaceae have colonized the far reaches of our planet save those most inhospitable: extreme poles, high mountain peaks, the most desolate deserts, and, of course, the deep waters of our lakes, rivers, and oceans.

Having evolved to occur in such a wide variety of habitats, as well as perfecting the ability to interact with and exploit myriad creatures as symbionts, orchids are the ideal plant family to teach us about biodiversity and illustrate its importance. The remarkable structures and colors of each and every orchid species convey a story about their ecology, evolution, and survival strategy. Once analyzed and unlocked, these stories give us powerful insight into the processes that have shaped our world for millennia and, hopefully, inspire us to conserve that which took millennia to create.

Masters of deception and manipulation, orchids are famous for lying and cheating their way to their many evolutionary successes. Exploring the manner in which they co-opt pre-existing behaviors of a bewildering cohort of pollinators of lilliputian dimensions is not only outstandingly instructive, but is just plain fun to contemplate. Even the venerable Charles Darwin referred to orchids as Splendid Sport and maintained a passion for them throughout his lifetime. It is undeniable that orchids have gripped the psyches of many humans. They have even, in recent years, become the most sold and cultivated type of ornamental plant. Their beauty alone does not explain this phenomenon.

Many theories exist as to why orchids are so alluring to us. It is thought that their zygomorphic (bilaterally symmetrical) flower structure influences us to see orchid flowers similarly to the way we see faces, attributing to them some personality in addition to their beauty. Some find the lip of certain orchids to be reminiscent of human anatomical parts that we normally keep covered, lending them a subliminal or feral attraction. Others simply find the combination of color, form, grace, and fragrance most appealing, yet not all orchids have traditionally attractive versions of these attributes. Some of the most compelling orchids are rank-smelling, muddy in coloration, and borne on clunky plants. Nothing adequately explains why people become so wildly obsessive about orchids. Ultimately, they are simply provocative creatures that manage to elicit strong reactions from pollinator and person alike.

In this book, we invite you to dip into the world of orchids and get to know these marvels of nature.

The orchid family, Orchidaceae, embraces 26,000 species in 749 genera and is one of the two largest families of flowering plants, the other being that of the daisies and lettuce, Asteraceae. Many people have a vague idea of what an orchid is, but it is likely that most would not recognize all the species included in this book as orchids. So, what is an orchid?

Orchids are divided into five subfamilies, Apostasioideae, Vanilloideae, Cypripedioideae, Epidendroideae, and Orchidoideae. This subdivision is based on DNA studies and morphology and reflects major differences in vegetative features and especially in the way orchid flowers are constructed. The five subfamilies have been recognized in the past as separate families by some botanists based on these distinctive characteristics, and the only characteristic they all share is that of how orchid embryos develop, from a structure called a protocorm, which is a small ball of cells without roots, stems, or leaves.

To develop into a mature orchid plant, a protocorm has to be successfully infected by a fungus, from which the developing orchid seedling obtains initially all the food (in the form of sugars) and minerals it needs to grow. As they start their life, orchids can be thought of as parasites on fungi. However, most but not all orchids as adults go on to develop roots and leaves, and produce their own food through photosynthesis. At a much later stage the continuing relationship of an orchid plant with the fungus can become mutually beneficial. In nature, the orchid exchanges sugars produced by its photosynthesis for minerals found more effectively by the fungus. In cultivation, the need of an orchid protocorm for a fungal partner can be replaced by manufactured sources of food and minerals, and many orchids are grown commercially using germination media with added sugars and minerals.

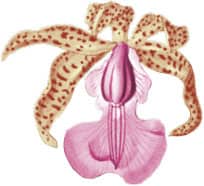

The other major trait that most botanists use to recognize an orchid is a structure called the gynostemium, or column, produced by the fusion of male (stamen) and female (stigma) parts in the flower. All but one of the five subfamilies share this feature. The exception is the subfamily Apostasioideae, consisting of only 14 species in two genera, Apostasia and Neuwiedia, which all lack complete fusion of the male and female parts.

The characteristically fused structure of the column, shared by 99.95 percent of all orchids, is responsible for the remarkable event where a pollinator, such as a bee, wasp, or moth, is maneuvered into doing exactly what the orchid wants. This allows the pollen, usually in the form of thousands of grains bound into a solid ball, or pollinium, to be placed on the animal in a precise manner and then, due to the close proximity of the stigma and anther (the part of the stamen holding the pollen), be precisely removed from that spot. Pollination in orchids is, therefore, a highly exact sequence of events, leading to fertilization of the thousands of developing orchid embryos in the carpel, or ovary, with just a single visit of a pollinator, provided that it has previously visited another flower of that same orchid species to pick up pollinia.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Little Book of Orchids»

Look at similar books to The Little Book of Orchids. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Little Book of Orchids and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.