If you want to know how white-collar criminals get away with heinous crimes in broad daylight, read Call Me Commander, the shocking tale of a massive fraud that wasnt discovered until some savvy journalists looked into the matter.

Renato Mariotti, former federal prosecutor and CNN legal analyst

This is the saga of the phony Commander Bobby Thompson, who paid esteemed lawyers and famous politicians to help him swindle tens of millions with a bogus veterans charity. It is also the inside story of tenacious reporters who brought down a colossal con and revealed the stunning true identity of the character behind it. The narrative sends a powerful message: now, more than ever, journalists are needed to help distinguish between what is real and what is fake in American life.

Dan Casey, columnist for the Roanoke Times

A wild ride and timely reminder that grifters love to prey on patriotism.

Spencer Ackerman, senior national security correspondent for the Daily Beast

Call Me Commander is a riveting account of one of the most twisted con men ever to hustle a buck in Florida, and nobody can tell this tale better than veteran investigative reporter Jeff Testerman, who first exposed the scam, and broadcast journalist Daniel Freed, who discovered the conmans secrets after his capture.

Craig Pittman, author of the New York Times bestseller Oh, Florida! How Americas Weirdest State Influences the Rest of the Country

Call Me Commander shows how [Bobby Thompsons] scam was constructed and how it unraveled when reporters began investigating. It might also be a cautionary tale about future cons when there are no more local journalists to investigate these scams.

Frank Abagnale, subject of the book and movie, Catch Me If You Can

Call Me Commander is a classic piece of investigative journalism. Its the type of work we grew up admiring, but, regrettablybecause of declining newspaper revenuesis fading into our past.

Robert E. ONeill, managing director of Freeh Group International Solutions and former U.S. attorney for the Middle District of Florida

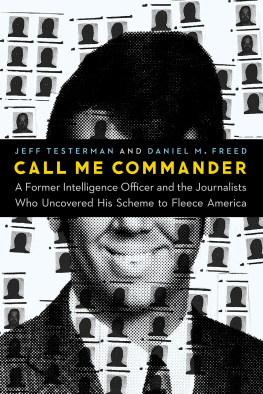

Call Me Commander

A Former Intelligence Officer and the Journalists Who Uncovered His Scheme to Fleece America

Jeff Testerman and Daniel M. Freed

Potomac Books

An imprint of the University of Nebraska Press

2021 by Jeff Testerman and Daniel M. Freed

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover images are from the interior.

Credit lines for uncaptioned images appear in the notes.

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Testerman, Jeff, author. | Freed, Daniel M., author.

Title: Call me commander: a former intelligence officer and the journalists who uncovered his scheme to fleece America / Jeff Testerman and Daniel M. Freed.

Description: [Lincoln]: Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020010719

ISBN 9781640123045 (hardback; alk. paper)

ISBN 9781640124073 (epub)

ISBN 9781640124080 (mobi)

ISBN 9781640124097 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Cody, John Donald. | Swindlers and swindlingUnited StatesBiography. | VeteransServices forUnited States. | CharitiesCorrupt practicesUnited States.

Classification: LCC HV 6692. C 63 T 47 2021 DDC 364.16/3092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020010719

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To Daniel, who persuaded me to help write this book; to my wife, Nancy, whom I trusted most for honest, constructive appraisals of my work; and to investigative journalists everywhere, who shine a light where no one else will.

Jeff

For my parents, who first taught me to ask questions, and my wife, who encourages me to do so.

Daniel

Contents

By the summer of 2015, Peter P. Strzok II had spent most of his adult life protecting the United States from foreign adversaries. Following four years with the armys 101st Airborne Division, Strzok devoted the next twenty-two years of his life to protecting U.S. national security as an agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

In the years to come, he would lead the investigation of Hillary Clintons emails and would work, for a time, for Robert Mueller as he looked into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. It was about a man who called himself the Commander.

Like other cases Strzok had worked, this one spanned the continent and crossed decades. It touched on national security, espionage, money, politics, lobbying, election meddling, assumed identities, elusive truths, and brazen lies. Having spent his career in the world of counterintelligence, the so-called Wilderness of Mirrorswhere up was down, and black was whiteStrzok knew about the Commander and thought someone else would like to hear his story too. Minutes after receiving the message that day in June, he forwarded it to Page.

Really interesting background on this, he told her. I will regale you over lunch one day if I havent already told you...

Please do, she responded.

Dr. Patrick Bray, an Ohio physician and navy veteran, was one of thousands of Americans who got a call in 2007 from a phone solicitor for a charity called the United States Navy Veterans Association. Bray had never heard of this particular charity. But the telemarketer on the line was courteous and knowledgeable, and the pitch was smooth. The phone solicitor talked about a new respect for veterans and how donations helped finance personal care packages being shipped to troops abroad. As a navy submarine and diving medical officer once separated from his wife by six-month deployments in places like Guam and Okinawa, Bray knew firsthand the psychological and material needs of service members at war and of veterans adjusting to life back home. He promptly sent a check for $150 to the Navy Veterans. A year later he sent another one for $300.

The hundreds of telemarketers calling on behalf of the Navy Veterans group were experts in coaxing potential contributors to open their checkbooks. If would-be donors explained they were senior citizens or retired or living on a fixed income, they were advised that the charity wasnt asking for a lot. After all, the telemarketers explained, a lot of our vets died in combat so that the two of us could be free today.

With patriotic passion gripping the nation following the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Americans were easily moved by the cause of its soldiers at war and veterans coming home. Donations for the Navy Veterans charity poured in. Most were small, ten or twenty dollars each. But they added up in a hurry. In 2007, the year Dr. Bray wrote his first check, the biggest telemarketing firm working for the Navy Veteransa Michigan company named Associated Community Servicesraised almost $7.4 million for the charity.

To an American public ready to believe they were lending a hand in the great fight of their generation, it all looked aboveboard and legitimate. Anyone who got a telemarketers call could check out the charity a dozen different ways, beginning by scrolling through the associations extensive website. Right up front was a listing of the executive board, including a photo of CEO Jack Nimitz in a blazer and striped tie, described as a no-nonsense navy man who was now a private investment banker from Texas.

Next page