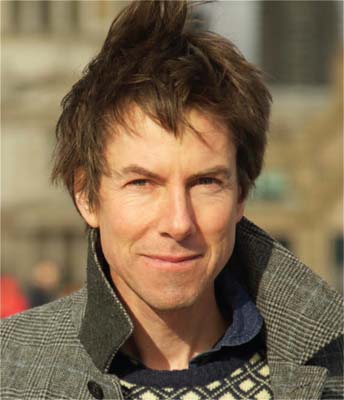

Michael Bond, who won the 2015 British Psychological Society Prize for The Power of Others, is a freelance science writer and editor. A consultant with New Scientist, he specializes in psychology and social behaviour, and how people interact with their environments.

Wayfinding

The Art and Science of

How We Find and Lose Our Way

MICHAEL BOND

To the hills of Invergeldie and all those who have walked in them.

Contents

List of Illustrations

In the text

In the plate section

Introduction

I F YOU HAVE EVER wondered what it feels like to be lost, my advice is, dont try it. The experience is terrifying and often traumatizing. People who are truly lost are usually incapable of making decisions that could save their lives, and they may even think they are going to die. They lose their minds as well as their bearings.

It is something of a miracle that we dont get lost more often. The physical world is infinitely complex, yet most of us are able to find our way around it. We can walk through unfamiliar streets while maintaining a sense of direction, take shortcuts along paths we have never used and remember for many years places we have visited only once. These are pretty remarkable achievements.

One of the purposes of this book is to explain how we do it: how our brains make the cognitive maps that keep us orientated, even in places that we dont know. More importantly, it is about our relationship with places, and how our understanding of the world around us affects our psychology and behaviour. The way we think about physical space has been crucial to our evolution. As well see in the opening chapter, the ability to navigate over large distances in prehistoric times gave Homo sapiens an advantage over the rest of the human family, allowing us to explore the furthest regions of the planet. As well as defining us as wayfinders, it has shaped some of our vital cognitive functions, including abstract thinking, imagination, aspects of our memory and even language. We are spatial in mind as well as body.

You will have felt this absolutely if you have ever been mentally ill. People with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, psychosis and related conditions commonly report feeling lost in their minds. This is not just a metaphor: mental illness affects the parts of the brain where cognitive maps form. Some psychologists believe that encouraging sufferers to navigate might reduce their symptoms by stimulating the growth of neurons in those areas. Wayfinding and spatial awareness not only help us find our way and connect us with our surroundings, they can also foster good mental health.

These considerations are especially relevant at a time when most of us are not using our spatial skills the way we always have. GPS-enabled devices allow us to get around without paying attention to where were going, and without exercising the cognitive faculties that have guided us for millennia. This book is not a remonstration against smartphones, but it does contain plenty of advice on how we can use satnav technology without compromising our cognitive health.

The book begins with the early history of human wayfinding and the systems our ancestors used to interact with the landscape. Chapter 2 investigates how these skills develop; children are instinctive explorers when they are allowed to be, though too often these days they arent, which means that their home range is generally much smaller than that of their grandparents. Chapter 3 explores the inner workings of the brains spatial system and the specialized cells that form cognitive maps, and provides an accessible primer in cutting-edge spatial neuroscience. Chapter 4 then considers the close association of space and memory in the brain and the many cognitive functions that depend on it.

The next two chapters examine the various mental strategies that people use to find their way, and why some of us are so much better at navigating than others. Chapter 7 tells the stories of some of the greatest navigators in history and attempts to understand what made them so good. We will then return to the question of why people get lost, and what happens to them when they do, in a chapter that is both a psychological enquiry and the story of a recent tragedy.

The idea of getting lost evokes images of dense forests and paths not taken, but as well see in Chapter 9 it can just as easily happen in cities, especially those that are confusingly arranged. Chapter 10 describes what happens to some of us at the end of our lives, when dementia robs us of our sense of place and we find ourselves in a world that we no longer know. Finally, we will reflect on the impact of GPS devices on our spatial abilities, and how we can prevent cognitive decline by exercising our natural navigation aptitude.

The book is the culmination of many small journeys: with search and rescue volunteers, psychologists, anthropologists, neuroscientists, animal behaviourists, psychogeographers, Polynesian sailors, US Army Rangers, Ordnance Survey cartographers, orienteering champions, map-makers, architects, urban planners, wayfinding designers, Alzheimers patients, early-twentieth-century aviators and modern-day adventurers. All these people have in their own way broadened our knowledge of how we interact with the world.

Peoples intense aversion to being lost illustrates how important it is for us to know where we are. One reason those with Alzheimers are deeply distressed much of the time is that their cognitive maps have all but disintegrated; they are incapable of finding their way anywhere and can be lost even in their own homes. My grandmother, in the final weeks of her life when she was affected by dementia, repeatedly used the phrase Am I here?. I used to wonder what she meant by it. Its a question with several possible meanings. The most obvious way to ask it is with your finger on a map, or with a certain location in mind. Yet the experience of a place can never be explained in coordinates or in terms of the firing patterns of your spatial neurons; you only really know where you are if you can tell a story about that place or remember how you found your way there. In the end, I believe my grandmother was questioning the history of her relationship with the room she was in, and perhaps whether she existed at all. In many ways it is the ultimate question, and one that all of us might ask at some point in our lives. Am I here? We want to hope so. What could matter more?

1

The First Wayfinders

A ROUND 75,000 YEARS AGO, a group of Homo sapiens left Africa, the continent where they had evolved, crossed the dried-up Bab el Mandeb strait at the southern end of the Red Sea and followed the coastline eastwards, along the sole of the Arabian peninsula. We dont know why they started this journey, nor why they didnt stop and try to settle along the way as other groups had done after all, they could not have conceived where they would end up. Over the next 60,000 years, their descendants trekked, paddled and bushwhacked their way east to the islands of south-east Asia and across the Arafura Sea to Australia, north through the Middle East and from there into China and the Steppes of central Asia, west over the Bosporus and down the Danube valley into Europe, and eventually, via a land bridge from Siberia, to America and on to its windswept southern toe. They have since endured and flourished in places that have proved more challenging than anything their ancestors faced in Africa: in dense rainforest and on remote islands, in the polar barrens of the high Arctic and on the mountain-bound Tibetan Plateau. Not content with treading the far reaches of this planet, they have also ventured 250,000 miles off it, to the Moon and beyond. In a few decades from now, their progeny could be kicking their feet in the dust of another planet, tens