The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For the Betsola

Texas is a world in itself.

Zane Grey, West of the Pecos

I have said that Texas is a state of mind, but I think it is more than that. It is a mystique closely approximating a religion.

John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley: In Search of America

Geographically and economically nature had thrown two hazards at the Texans: unlimited space, seemingly unlimited wealth.

Edna Ferber, A Kind of Magic

Of course its a story about Texas. But only because Texas, right now, represents the American dream in a special wayas the place where there is perhaps the most dramatic realization of material possibilities.

George Stevens, interview

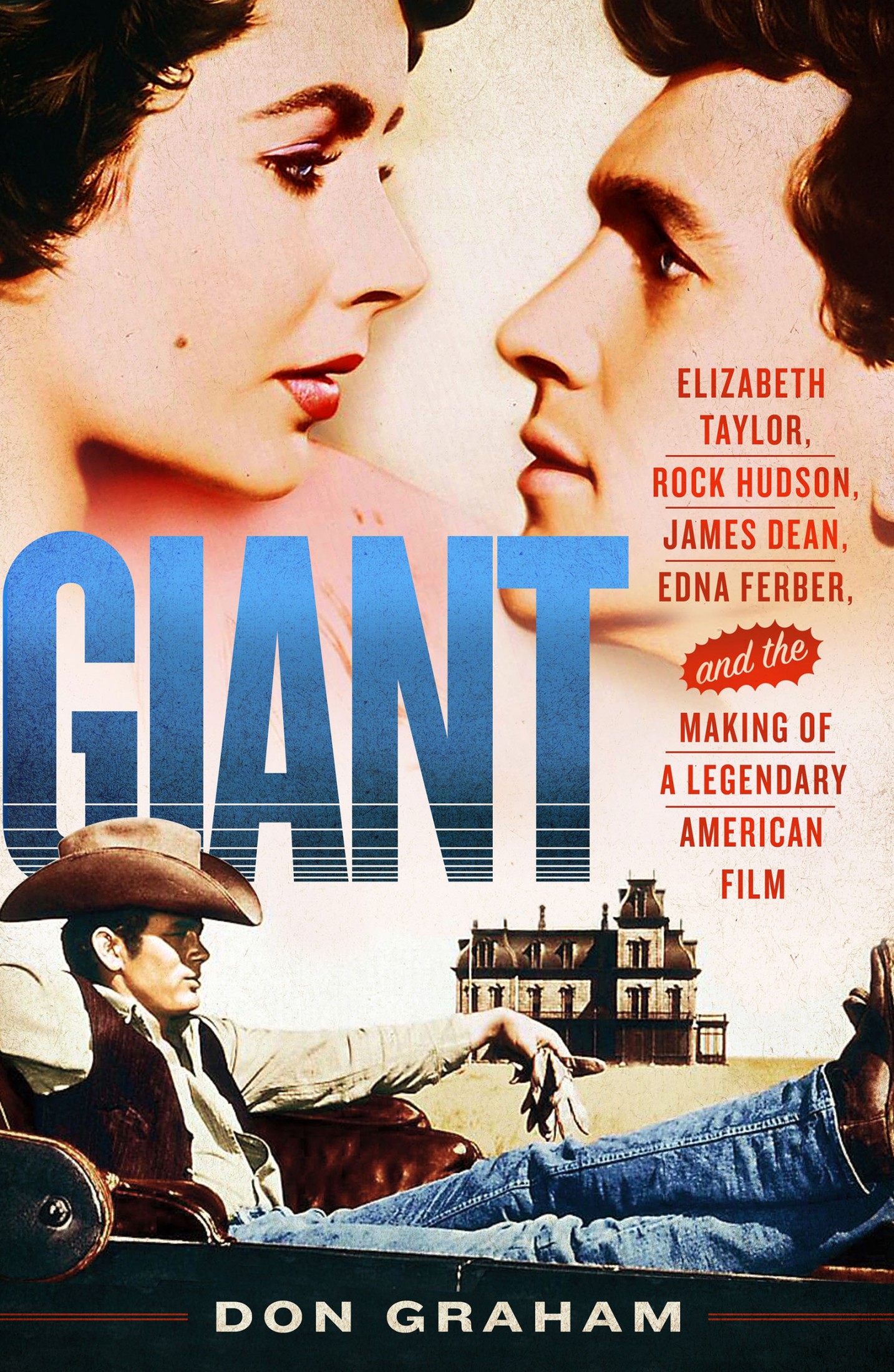

On May 12, 1955, director George Stevens and producer Henry Ginsberg sent a folksy telegram inviting members of the press to attend an Off-to-Texas Luncheon. Six days later, the Chuck Wagon opened at 12:30 at Warner Bros. Studio, and some thirty-odd journalists forgathered to celebrate, at long last, the launching of Giant, the much-ballyhooed film that was going to be made from Edna Ferbers bestselling novel. It had taken Stevens and Ginsberg only three years to reach this point, and everybody was in a festive mood. Besides the local press, journalists from Life, Time, Look, Good Housekeeping, Seventeen, and Newsweek were on hand. Some names were semifamous: Sheilah Graham, Bow-Wow Wojciechowicz, Joe Hyams.

Entering the commissary, the guests filed through glass doors into a smaller and more formal dining area where photographs of stars adorned the walls. This was the fabled Green Room, the inner sanctum, with banquettes and tablecloths and fancy silverware and waiters so that the stars and executives didnt have to stand in line. It was a sign of status to dine in the Green Room.

On this day, a Texas flag graced every table, and guests were treated to huge slabs of Texas steaks and an enormous cake in the shape of Texas, dotted with tiny trees, candy sagebrush, and oil derricks made of spun sugar. An accordionist played The Eyes of Texas Are Upon You, and composer Dimmy Tiomkin cracked that George Stevens cried every time he heard that song.

Jack Warner, or the Colonel, as many called him, the nattily dressed, mustachioed majordomo of Warner Bros., hurried in and made a few brief remarks, including a couple of bad jokes. Not even his closest friends could ever recall the Colonels telling a funny one. Jack Benny quipped that Jack Warner would rather tell a bad joke than make a good movie. Nobody ever forgot his toast to Madame Chiang Kai-shek at a gala party at his Hollywood mansion: Madame, I have only one thing to say to youNo Tickee, No Laundry. When a flat-footed joke fell flat, as it invariably did, he would break into a soft-shoe routinea throwback to his teenage days on the vaudeville circuit in Ohio. But he was truly funny when he played his best role, a tough Jew who knew how to deal with filmmakers who thought they were creating art. When Warren Beatty tried to sell a skeptical Warner on the merits of Bonnie and Clyde, Beatty said to him, This is really a kind of homage to the Warner Bros. gangster films of the 30s, you know? And the clown prince of Hollywood said, What the fucks an homage?

Warner handed out copies of Ferbers novel, signed by members of the cast, to the press. I know I wont have to tell you the wonderful story because youll all stay up nights reading it, he said. He closed with a remark addressed specifically to his strong-willed director: I want to thank you all for coming. I hope we will all meet again when the pictures overin the not TOO-long-distant future! That did draw a laugh.

Coming in on time and under budget was always the Colonels goal, and he hated overruns. With a schedule pegged at seventy-seven days and a budget of $2.7 million, Warner had reason to be concerned, because the man at the helm, the often inscrutable George Stevens, might have been listening or he might have been whistling under his breath The Yellow Rose of Texas. Earlier that year, as Giant moved inexorably toward its as-yet-undetermined starting date, Jack Warner wrote Stevens a memo expressing his acute anxiety: Is there some way in your rewriting and polishing that you can maintain the same dramatization and still aim for a two hour show rather than the length I am sure youre going to wind up with; namely, two hours and twenty-five or thirty minutes? Warner was only about an hour short of what the immovable Stevens would deliver.

It was well known in the industry that Stevens would almost certainly take as long as he thought necessary to make the film he envisioned. Indeed, members of the press were already making wagers on how far behind schedule the production would fall. At age fifty, resolute, stubborn, and assured in his craft, Stevens had been directing films since the silent era and had to his credit early hits like Alice Adams (1935), Gunga Din (1939), and Woman of the Year (1942). More recently, he had snagged an Oscar for directing A Place in the Sun (1951) and was nominated for Shane (1953). He was at the top of his game. He also enjoyed great prestige within the power-elite circles of the industry, twice serving as president of the Directors Guild and receiving the Irving Thalberg Award in 1953. During the worst days of the blacklist, Stevens had put up a stiff, principled fight, and according to Fred Zinnemann, younger members of the Guild regarded him as a sort of pope or certainly a cardinal.

Introduced as the giant behind Giant, Stevens read aloud an affectionate telegram from Edna Ferber. Addressed to Henry and George and all you boys and girls gathered together at the Warner studio, it expressed how much she would have liked to have been there for the start of the filming. Giant interested and fascinated her much more than the screen career of my other novels or plays, which was saying a good deal, because twenty-one of her works had been filmed so far. She went on: Under George Stevens magic direction the stone and mortar and beams that hold the structure will not show at all but theyll be there. Finally, she wished everybody good luck, which is really just slang for hard work.

Then Stevens presented the cast. There was Rock Hudson, a dark horse borrowed from Universal, where he had made films like Taza, Son of Cochise, in which he played a very tall, very bronzed Apache, and, most recently, Magnificent Obsession, a Douglas Sirk melodrama that augured a bright future for the rising star. But Giant offered the best role yet. Rock was twenty-nine and top-of-the-mountain stardom was within reach. One correspondent underlined the roles importance for Rocks future: Theres better than an even chance that under Stevens guidance Hudson might take on the dramatic stature he so badly needs. In short, Stevens may do for Hudson what he did for Miss Taylor at a vital point in her career. According to several scribes, Hudson was wearing a ten-gallon hat to hide the attempt by makeup men to make him look bald as he aged toward the end of the film. This method of aging Hudson was shelved later on, and its very doubtful that he was wearing a ten-gallon hat, the tall-crowned western headgear that went back to the days of Tom Mix and was reincarnated by Hopalong Cassidy. In all likelihood, Rock was wearing a Stetson like the one he wears in the film, but the tenderfoots in the press saw all western hats as ten-gallon ones.