Contents

Page List

Guide

Cover

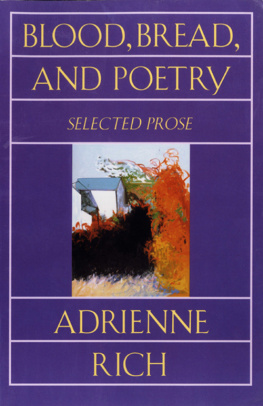

THE RHS BOOK OF

FLOWER

POETRY &

PROSE

Selected by Charles Elliott

With illustrations from the

Royal Horticultural Societys Lindley Library

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Writers seem always to have had some sort of connection with flowers, if only to help convey their own states of mind, and literature from the time of Solomon (if not before) is studded with references to particular plants. Some species have always been special favourites its not long since no self-respecting poet could avoid tossing into his verse mention of a rose or a lily, generally in reference to an attractive or yearned-for damsel.

Formulaic usage aside, however, it is clear that many of our finest writers were honestly and deeply moved by flowers, and regarded them as a precious part of their mental world. When Shakespeare speaks of the way daffodils take The winds of March with beauty or Chaucer says of the daisy that Of al the floures in the mede, Thanne love I most thise floures white and rede, their words are obviously not mere bits of poetic apparatus. The flowers have touched the poet and he is able in turn to touch us through them.

Until relatively recently, of course, most writers did not consider flowers closely and with precision. Symbols were easier to manipulate than stamens, the authors emotions more important to him than the shape of an umbel. But there was one category of writing, not strictly speaking literary at all, that combined detailed observation with fresh and exciting language. This was the work of plantsman-herbalists like John Gerard and John Parkinson, men fascinated by growing things, especially in terms of their medical application. John Milton, as a classicist inescapably aware that its name meant unfading, could praise the immortal amaranth without betraying any interest at all in its drooping crimson panicles; Gerard, on the other hand, gets right to the heart of violet-ness, Parkinson to the essence of an anemone, the real thing, while Sir Thomas Hanmer expresses his delight in the great diversity of hyacinths. These men were gardeners; they looked at their plants before writing about them.

And so did the rural poet John Clare, though his plants tended to be wild rather than garden varieties. Like Robert Burns, another countryman with a keen eye, Clare brought new eloquence to writing about nature. Direct and seemingly unsophisticated, his verses on individual species lily of the valley, primrose, and many others are botanically precise yet somehow deeply and even painfully human, spoken in the voice of man whose world was dying around him. The combination is extraordinary, and probably unmatched.

Moving closer to our own times, once the shoal of Victorian sentimentalists has been safely crossed the choice of writers about flowers grows broad indeed. There are the essayists like Canon Ellacombe and E.A. Bowles, whose subject is their own garden and its much-loved contents; nature writers like Henry Williamson, W.H. Hudson and John Burroughs; great horticulturalists like Gertrude Jekyll, Reginald Farrer, Margery Fish and others, whose writings not only teach but inspire; and poets capable of engaging with flowers so intimately that it shakes you. In the latter category must be Theodore Roethkes poem on orchids, Anne Stevenson writing about Himalayan balsam and above all D.H. Lawrences Bavarian Gentians. The only problem for the anthologist is where to stop. The garden goes on and on.

Charles Elliott

CROCUS

See the crocus golden cup

Like a warrior leaping up

At the summons of the spring,

Guard turn out! for welcoming

Of the new elected year.

The blackbird now with psalter clear

Sings the ritual of the day

And the lark with bugle gay

Blow reveille to the morn,

Earth and heavens latest born.

Joseph Mary Plunkett, See the Crocus Golden Cup (1916)

QUEEN ANNES LACE

Her body is not so white as

anemone petals nor so smooth nor

so remote a thing. It is a field

of the wild carrot taking

the field by force; the grass

does not raise above it.

Here is no question of whiteness,

white as can be, with a purple mole

at the center of each flower.

Each flower is a hands span

of her whiteness. Wherever

his hand has lain there is

a tiny purple blossom under his touch

to which the fibres of her being

stem one by one, each to its end,

until the whole field is a

white desire, empty, a single stem,

a cluster, flower by flower,

a pious wish to whiteness gone over

or nothing.

William Carlos Williams, Queen Annes Lace (1921)

TULIP

I was very much pleased and astonished at the glorious show of these gay vegetables, that arose in great profusion on all the banks about us. Sometimes I considered them with the eye of an ordinary spectator, as so many beautiful objects varnished over with a natural gloss, and stained with such a variety of colour, as are not to be equalled in any artificial dyes or tinctures. Sometimes I considered every leaf as an elaborate piece of tissue, in which the threads and fibres were woven together into different configurations which gave a different colouring to the light as it glanced on the several parts of the surface. Sometimes I considered the whole bed of tulips, according to the notion of the greatest mathematician and philosopher that ever lived, as a multitude of optic instruments, designed for the separating of light into all those various colours of which it is composed.

Joseph Addison, Tatler (1710)

IRIS

Thou art the iris, fair among the fairest,

Who, armed with golden rod,

And wingd with the celestial azure, bearest

The message of some god.

O! flower-de-luce, bloom on, and let the river

Linger to kiss thy feet!

O! flower of song, bloom on, and make for ever

The world more fair and sweet.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Flower-de-luce (1867)

BLUEBELL