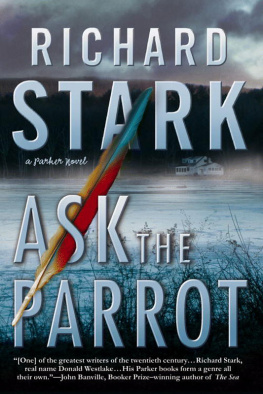

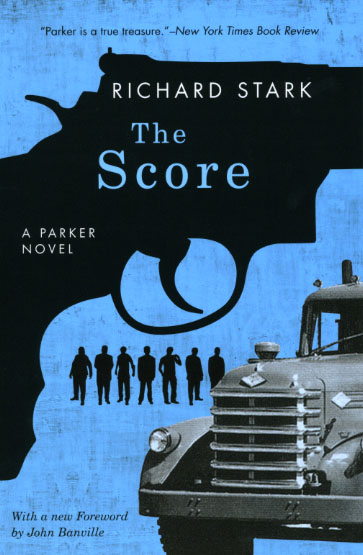

The score / Richard Stark ; with a new foreword by John Banville.

p. cm.

Summary: The fifth Parker novel has the main character planning a score that involves a dozen professional crooks ready to take over a rich, remote North Dakota town.

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-77104-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-77104-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Parker (Fictitious character).

I. Banville, John. II. Title.

THE PARKER NOVELS

John Banville

It was in the 1960s that Richard Stark began writing his masterly series of Parker novelsat last count there were twenty-four of thembut they are as unrepresentative of the Age of Aquarius as it is possible to be. Try imagining this most hardened of hard-boiled criminals in a tie-dyed shirt and velvet bell-bottoms. Parker does not do drugs, having no interest in expanding his mind or deepening his sensibilities; he cares nothing for politics and is indifferent to foreign wars, although he fought or at least took part in one of them; he would rather make money than love and would be willing to give peace a chance provided he could sneak round the back of the love-in and rob everybody's unattended stuff. When he goes to San Francisco it is not to leave his heart therehas Parker got a heart?but to retrieve some money the Outfit owes him and kill a lot of people in the process.

The appeal of the conventional crime novel is the sense of completion it offers. Life is a messwe do not remember being born, and death, as Ludwig Wittgenstein wisely observed, is not an experience in life, so that all we have is a chaotic middle, bristling with loose ends, in which nothing is ever properly over and done with. It could be said, of course, that all fiction of whatever genre offers a beginning, middle, and endeven Finnegans Wake has a shapebut crime fiction does it best of all. No matter how unlikely the cast of suspects or how baffling the strew of clues in an Agatha Christie whodunit or a Robert Ludlum thriller, we know with a certainty not afforded by real life that when the murderer is unmasked or the conspiracy foiled, everything will click into place, like a jigsaw puzzle assembling itself before our eyes. The Parker books, however, take it as a given that if something can go wrong, it will, and that since something always can go wrong, it invariably does.

Indeed, this is how very many of the Parker stories begin, with things going or gone disastrously awry. And Parker is at his most inventive when at his most desperate.

We first encountered Parker in The Hunter, published in 1962. His creator, Donald Westlake, was already an established writerhe adopted the pen name Richard Stark because, as he said in a recent interview, When you're first in love, you want to do it all the time, and in the early days he was writing so much and so often that he feared the Westlake market would soon become glutted.

Born in 1933, Westlake is indeed a protean writer and, like Parker, the complete professional. Besides crime novels, he has written short stories, comedies, science fiction, and screenplayshis tough, elegant screenplay for The Grifters, adapted from a Jim Thompson novel, wasnominated for an Academy Award. Surely the finest movie he wrote, however, is Point Blank, a noir masterpiece based on the first Parker novel, The Hunter, directed by John Boorman and starring Lee Marvin. Anyone who saw the film will consider Marvin the quintessential Parker, though Westlake has said that when he first created his relentless herohero?he imagined him looking more like Jack Palance.

In that first book, The Hunter, Parker was a rough diamondI'd done nothing to make him easy for the reader, says Westlake, no small talk, no quirks, no petsand looked like a classic pulp fiction hoodlum:

He was big and shaggy, with flat square shoulders and arms too long in sleeves too short. His hands, swinging curve-fingered at his sides, looked like they were molded of brown clay by a sculptor who thought big and liked veins. His hair was brown and dry and dead, blowing around his head like a poor toupee about to fly loose. His face was a chipped chunk of concrete, with eyes of flawed onyx. His mouth was a quick stroke, bloodless. (p. 34)

Even before the end of this short book, however, we see Westlake/Stark begin to cut and burnish his brand-new creation, giving him facets and sharp angles and flashes of a hard, inner fire. He has been betrayed by his best friend and shot by his wife, and now he is owed money by the Outfitthe Mafia, we assumeand he is not going to stop until he has been repaid:

Momentum kept him rolling. He wasn't sure himself any more how much was a tough front to impress the organization and how much washimself. He knew he was hard, he knew that he worried less about emotion than other people. But he'd never enjoyed the idea of a killing. It was momentum, that was all. Eighteen years in one business, doing one or two clean fast simple operations a year, living relaxed and easy in the resort hotels the rest of the time with a woman he liked, and then all of a sudden it all got twisted around. The woman was gone, the pattern was gone, the relaxation was gone, the clean swiftness was gone. (p. 171)

The fact is, though Parker himself would be contemptuous of the notion, he is the perfection of that existential man whose earliest models we met in Nietzsche and Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky. If Parker has ever read Goetheand perhaps he has?he will have recognized his own natural motto in Faust's heaven-defying declaration: Im Anfang war die Tat [In the beginning was the deed]. Donald Westlake puts it in more homely terms when he says that, I've always believed the books are really about a workman at work, doing the work to the best of his ability, and when in the context of Parker he refers to Hemingway's judgment on people, that the competent guy does it on his own and the incompetents lean on each other.

In Parker's world there is no law, unless it is the law of the quick and the merciless against the dim and the slow. The police never appear, or if they do they are always too late to stop Parker doing what he is intent on doing. Only twice has he been caught andbrieflyjailed, once after the betrayal by his wife and Mal Resnick, which sets The Hunter in vengeful motion, and another time in the recent Breakout. Parker treats the law-abiding world, that tame world where most of us live, with tight-lipped impatience or, when one or otherof us is unfortunate enough to stumble into his path and hinder him, with lethal efficiency. Significantly, it is the idea of a killing that he has never enjoyed; this is not to say that he would enjoy the killing itself, but that he regards the necessity of murder as a waste of essential energies, energies that would be better employed elsewhere.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.