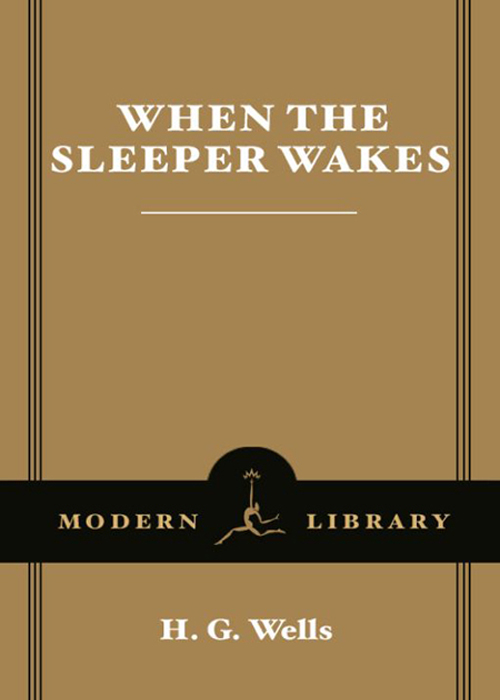

H.G. Wells - When the Sleeper Wakes

Here you can read online H.G. Wells - When the Sleeper Wakes full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2003, publisher: Modern Library, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:When the Sleeper Wakes

- Author:

- Publisher:Modern Library

- Genre:

- Year:2003

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

When the Sleeper Wakes: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "When the Sleeper Wakes" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

When the Sleeper Wakes — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "When the Sleeper Wakes" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

Orson Scott Card

Why are the writings of H. G. Wells still in print, still important, still worth reading today?

H. G. Wells was an important literary figure during his lifetime. But so, in their day, were Edmund Spenser and Thomas Gray. Edmund Spensers The Faerie Queene was considered, in its time, to be the finest achievement of English literature. Grays Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard was one of the most memorized, most quoted poems in public life for at least a century, with tag lines like mute inglorious Miltons and far from the madding crowd that showed up in so many other peoples writing and speaking that we can only conclude that every educated speaker of the English language was expected to have read it.

And yet today it is rare for either work to find readers outside the college classroom. H. G. Wells, on the other hand, published his first short novel, The Time Machine, more than a century ago, but it is still read, not just by students required to study it, but also by volunteersreaders who pick it up, not because they will have to write an essay about it, but because they hope to derive pleasure from the reading.

Spensers Faerie Queene represented two genres of writing that are both dead as far as the reading public is concerned. It was an allegory, in which the characters and objects and events did not so much represent themselves in the fictional story as they did ideas and events in the outside world; and it was an epic poem, meant to explain the heritage of a nation. Once these genres ceased to have a public following, Faerie Queene faded along with them.

Grays Elegy was in the vigorous category of essays in verse, in which a poet has an experience that prompts him to think various deep thoughts, all of which are presented in rhythm and rhyme so that the sheer sound of the language is a pleasure, along with the images and ideas. How could such a vibrant genre ever die?

And yet die it did, at least as a part of the public life of educated people. I know a good many poets who would argue passionately that I am wrong, but one has only to look at what is published in those journals that still persist in publishing poetry. How many poems are longer than twenty lines? Forty? Sixty? It is possible to argue that Gray opened the great day of this genre, and T. S. Eliot closed it; but wherever the honor or blame might be bestowed, it cannot be credibly argued that the genre is not, effectively, dead.

Nobody comes out of a movie or puts down a novel and says, Oh, if only they could adapt this story into an epic poem! Nor does anyone emerge from the theater or the book and immediately record his experience and thoughts in a hundred-line essay in verse. Or if someone does, it is without the faintest hope that it will find an audience larger than the number of the poets most patient friends.

H. G. Wellss work remains alive because the genre that he createdscience fictionremains alive, and its readers and writers remember Wells as one of the fathers of their field. More importantly, his novels remain within the mainstream of contemporary science fiction. It is not such a far leap to go from the work of Bruce Sterling or Connie Willis, Isaac Asimov or Robert Heinlein to the work of H. G. Wells.

A genre of literature remains alive as long as there is an audience that persists in seeking it out and reading it for the pleasure of it. It can also have a kind of secondary life, a bit like a suit of armor in a museum, as long as teachers make it the awful duty of students to know works in that genre that they would never have chosen for themselves. But the preservation and admiration of an artifact does not mean that it is not dead. Few choose to churn butter when they can buy it by the pound in the grocery store, or spend their days spinning thread so they can weave the cloth to make their own clothing.

I believe that storytelling is as vital to human life as butter churning or spindle and distaff or suits of armor ever were. There is no human society that does not devote some part of their lives to hearing tales and songs that give voice to their own experience and provide them with memories of experiences they have never had.

But the means of storytelling changes, and so does the audience.

For many centuriesfrom Roman times through the Middle Agesthe preferred storytelling genre was the romance. (Not the love story that we associate with that word today, but any kind of tale of the lives of heroes that includes their love affairs along with their heroic deeds.)

Romances could deal with terrible crimes and the vengeance that ensued, or with adultery leading to war, or any number of extravagant events. There was often magic and sometimes religion (less often than you might expect), but one thing was certain: Romance rarely bore much relation to the ordinary life of the members of the audience.

The fashion of jousting long outlasted its utility as training for battlebecause romances made it seem wonderful and, of course, romantic to dress up in armor and try to knock someone off his horse. But as the printing press spread literacy to an ever-increasing number of people and to social classes that previously got their stories from mummers and players, some writers began to seek to write about lives of real people. And so the novel was bornthe romance nouvelle, the new romance that did away with the deeds of great heroes and instead told of the sorts of people readers might expect to actually meet in real life.

Daniel Defoes Robinson Crusoe, considered by many to be the first commercially successful novel, might seem to be pretty extravagant, but think again. The novel concerns itself with something that was not that uncommon in Defoes dayshipwreck. And when the book came out, much of the original audience was quite familiar with the true story of Alexander Selkirk, who was put ashore (at his own request) on a rarely visited island, where he survived for five years before being rescued.

The novel concerns itself not with heroic deeds, but with the practical problems of staying alive without technology. What the audience saw was not magic or battles or vengeance or thwarted lovethey saw a man who had to swim out to a wrecked ship to retrieve supplies hed need in order to survive. The readers in Defoes day knew that everything that happened in Crusoe might really happen.

And in short order other writers, liberated or motivated by the commercial success of Defoes novel, began their own stories of perfectly believable people dealing with difficult problems. When one reads Pride and Prejudice it might not come to mind that Austen owed any debt to Robinson Crusoe, but she did. Because if there had been no audience for novels about real people leading seemingly ordinary lives, Austen would not have undertaken to write her books.

Which brings us, again, to the relationship between H. G. Wells and todays literary genre of science fiction.

Wells did not invent science fiction. Jules Verne had already written his extraordinary series of novels (or, arguably, romances) in which lone scientists or adventurers achieve the technology to do previously impossible things. Like Wellss, Vernes works continue to be read by volunteers in the English-speaking worldand in translation, no less.

Yet, oddly enough, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «When the Sleeper Wakes»

Look at similar books to When the Sleeper Wakes. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book When the Sleeper Wakes and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.