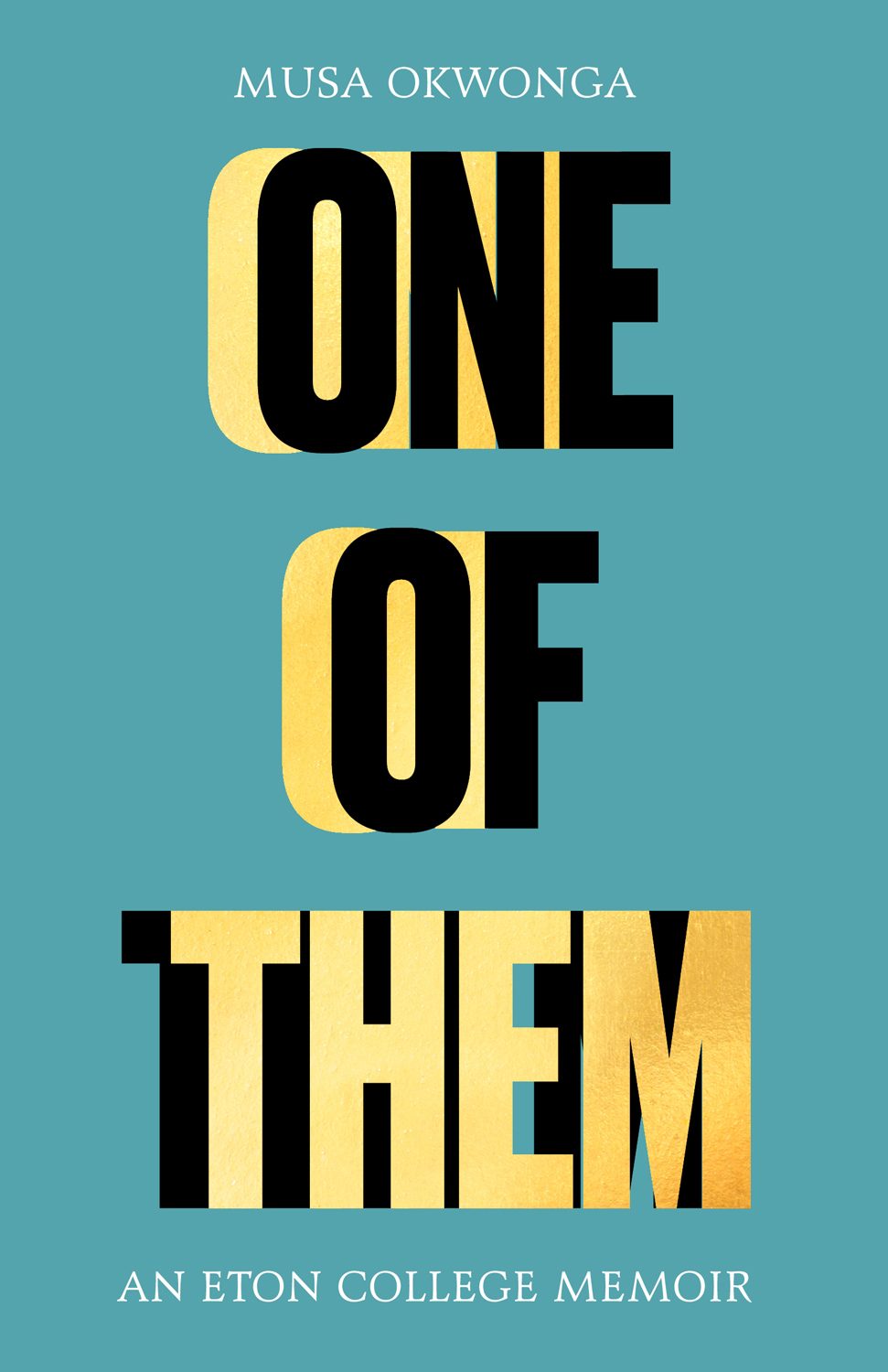

There are precisely two types of immigrant: those who manage to avoid detection by the most hostile forces in their society, and those who do not. This is the story of my attempt to be the former.

With gratitude to Winston Bell-Gam

for his generous support of this book

PART ONE

MOSTLY PEACEFUL

JUST LIKE BEING AT SCHOOL AGAIN

One day I receive an email from an old friend, asking if I am coming to the school reunion. A few days later I receive another. The people at school are trying to get hold of you , they say, but they dont know how . I am one of about a dozen boys from my year of just over 250 students whom they refer to as lost leavers, those whose contact details they no longer have, and they would like to invite me to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of my departure. Theyve put out a list of names to all the old boys in my age group, just in case some of them are in touch with me. Will you be coming along? they ask. It would be good to see you .

I pause before replying to the email, which is always revealing: I always hesitate before delivering news people might not like. I dont want to go. A school reunion is essentially a referendum on whether I am happy to display the life I have made in front of my contemporaries, and if I am truthful with myself, then the answer is no.

My best friend from school then gets in touch. Im not sure about this, I say to him. I could tell, he replies. He will be attending the reunion. He is a successful executive, a married father of two, with a career that has taken him across the world and back. I might feel more comfortable going back there if I was him, but Im not; Im a childless, unmarried writer who cant afford to buy his mother a house.

I wonder if I am being oversensitive and so I explain my doubts to another close schoolfriend, who will be attending the reunion too. I just dont feel that I have very much to show for the last twenty years, I say. Thats nonsense, he says at once, but he understands my reluctance; he knows Im not looking forward to peoples judgement of my life choices. Some friends will tell me that I compare myself too harshly to my peers, but he gets it. That is precisely what my school has brought me up to do: to compete endlessly with those nearby, even as I seek my own way.

His path has been very different from mine, but he has always respected my direction. He and his wife, a couple so attractive they should be taxed for it, live with their young son in London, where they have carved out fulfilling careers in the legal profession. I try to see them at least once a year when I am back from Berlin, where I now live, but our diaries are more and more unforgiving as time goes by. I dont think Ill go.

What have I done with my life? My school asks me this every decade, whenever it has a reunion, and the last time they did so the answer was: So far, so good . I had published two acclaimed books about football and several of my contemporaries had read them. I was on my way to a black-tie dinner with some of the games most celebrated players. I was running one of the most successful poetry nights in London and had made a promising start to a career in music.

Ten years later, I havent yet published a third book about football, and I have had to publish my own poetry because no one else would. I am barely making music any more, partly because that scene has been ravaged by internet piracy, and though I am making my name as a journalist, the industry is imploding. On social media I see many friends of mine provide summaries of their last ten years and all the things they have done in that time. I dont write a summary. My best years are ahead, I tell myself. They have to be.

Theres another reason I dont want to go back to school, which is that it feels like the bad guys have won. A few years before I arrived at my school, it was attended by a cluster of people who now hold political office in Britain: a group who have driven through some of the most socially regressive policies in recent memory, and whose leader, the current prime minister, is best known for his arrogance and dishonesty. I was so proud of my school when I was there, but now I wonder what kind of place it was if these are its most prominent alumni. I ask myself whether this was my schools ethos: to win at all costs; to be reckless, at best, and brutal, at worst. I look at its motto again May Eton Flourish and I think, yes, many of our politicians have flourished, but to the vast detriment of others. Maybe we were raised to be the bad guys?

I dont think I was, but I am not so sure any more, because if I wasnt, then where is the resistance? Where are the good guys from my school who are speaking up against the bad ones? I dont see many of them arguing for a more compassionate world in the public sphere, or funding media organisations or progressive causes; not nearly on the same scale that the bad guys are. I tell a schoolfriend this and he says, Maybe they are working hard behind the scenes, and I say that even if this is happening which I very much doubt then it is not good enough. It is just like being at school again, I think. Just like being at school, when people would complain furiously about the few boys who ran the place, but never actually said anything to their faces.

Just like being at school again. The invitation to my reunion and the rise of another one of my schools old boys to the office of prime minister have brought me abruptly and painfully back to my teenage years. Maybe I need to stay here awhile, to see why these feelings are still so severe.

LOOKING FOR ME

Years later, a few people will look forgivingly upon those who went to Eton, saying that it is not their fault that their parents sent them there. They will say that these boys are not to blame for choosing to attend a place whose most famous alumni are now wrecking the country and causing so much anger elsewhere around the planet. I will read and hear their words and I will think: But I did choose it, and I was proud when I did so.

I remember that day well. I was eleven years old, and a documentary came on television celebrating the 550th anniversary of a world-famous boarding school. I was transfixed. Everything they did there seemed so important the routines, the rituals. How did a simple school get to look so grand? At that time, I was attending a normal-sized school the kind of school that only came into view once my mothers car drove over a small railway bridge. But this school I was seeing on television, it was the size of a town. Years later, when I am landing in Heathrow, I will be able to see it easily from the air and will always look for it as I descend. Sometimes I will even be able to pick out my boarding house, from which I saw countless planes come in as I worked at my desk; how many of those who studied where I did were in those planes then, looking down just as I looked up, looking for me?

This school! Two weeks later, by complete coincidence, I will visit it for a school trip, and I will get to see its majesty up close. Its bricks are five times as old as those of my home town. It has statues of kings and monuments to biblical heroes. It is part museum, part war memorial. It has several great halls and not one church but two, these vast buildings of forbidding stone and marvellous stained glass. Places of worship that God himself might attend.

I get home from my school trip and I speak to my mother that evening. I have to go to that school, I tell her. I have to. My mother is surprised by my determination, and I am even more surprised by how quickly she agrees. After all, the change will not be convenient for her. I have just won a place at the local grammar school, which I am set to attend free of charge, and now I want to go to an institution which, over the next few years, will cost her tens of thousands of pounds.