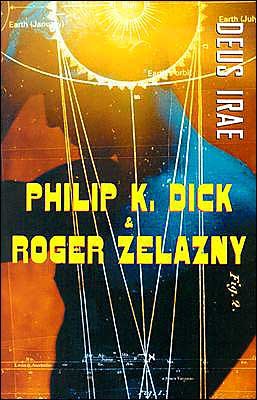

Annotation

In the years following World War III, a new and powerful faith has arisen from a scorched and poisoned Earth, a faith that embraces the architect of world wide devastation. The Servants of Wrath have deified Carlton Lufteufel and re-christened him the Deus Irae. In the small community of Charlottesville, Utah, Tibor McMasters, born without arms or legs, has, through an array of prostheses, established a far-reaching reputation as an inspired painter. When the new church commissions a grand mural depicting the Deus Irae, it falls upon Tibor to make a treacherous journey to find the man, to find the god, and capture his terrible visage for posterity.

Deus Irae

by Philip K. Dick & Roger Zelazny

This novel, in loving memory, is dedicated to Stanley G. Weinbaum, for his having given the world his story A Martian Odyssey.

One

Here! The black-spotted cow drawing the bicycle cart. In the center of the cart. And at the doorway of the sacristy Father Handy glanced against the morning sunlight from Wyoming to the north as if the sun came from that direction, saw the churchs employee, the limbless trunk with knobbed head lolling as if in trip-fantastic to a slow jig as the Holstein cow wallowed forward.

A bad day, Father Handy thought. For he had to declare bad news to Tibor McMasters. Turning, he reentered the church and hid himself; Tibor, on his cart, had not seen him, for Tibor hung in the clutch of within-thoughts and nausea; it always came to this when the artist appeared to begin his work: he was sick at his stomach, and any smell, any sight, even that of his own work, made him cough. And Father Handy wondered about this, the repellency of sense-reception early in the day, as if Tibor, he thought, does not want to be alive again another day.

He himself, the priest; he enjoyed the sun. The smell of hot, large clover from the surrounding pastures of Charlottesville, Utah. The tink-tink of the tags of the cows he sniffed the air as it filled his church and yetnot the sight of Tibor but the awareness of the limbless mans pain; that caused him worry.

There, behind the altar, the miniscule part of thework which had been accomplished; five years it would take Tibor, but time did not matter in a subject of this sort: through eternityno, Father Handy thought; not eternity, because this thing is man-made and hence cursedbut for ages, it will be here generations. The other armless, legless persons to arrive later, who would not, could not, genuflect because they lacked the physiological equipment; this was accepted officially.

Uuuuuuuub, the Holstein lowed, as Tibor, through his U.S. ICBM extensor system, reined it to a halt in the rear yard of the church, where Father Handy kept his detired, unmoving 1976 Cadillac, within which small lovely chickens, all feathered in gay gold, luminous, because they were Mexican banties, clung nightlong, bespoiling and yet, why not? The dung of handsome birds that roamed in a little flock, led by Herbert G, the rooster who had flung himself up ages ago to confront all his rivals, won out and lived to be followed; a leader of beasts, Father Handy thought moodily. Inborn quality in Herbert G, who, right now, scratched within the succulent garden for bugs. For special mutant fat ones.

He, the priest, hated bugs, too many odd kinds, thrust up overnight from the falt so he loved the predators who fed on the chitinous crawlers, loved his flock ofamusing to think ofbirds! Not men.

But men arrived, at least on the Holy Day, Tuesdayto differentiate it (purposefully) from the archaic Christian Holy Day, Sunday.

In the hind yard, Tibor detached his cart from the cow. Then, on battery power, the cart rolled up its special wood-plank ramp and into the church; Father Handy felt it within the building, the arrival of the man without limbs, who, retching, fought to control his abridged body so that he could resume work where he had left off at sunset yesterday.

To Ely, his wife, Father Handy said, Do you have hot coffee for him? Please.

Yes, she said, dry, dutiful, small, and withered, as if wetless personally; he disliked her body drabness as he watched her lay out a Melmac cup and saucer, not with love but with the unwarmed devotion of a priests wife, therefore a priests servant.

Hi! Tibor called cheerfully. Always, as if professionally, merry, above his physiological retching and reretching.

Black, Father Handy said. Hot. Right here. He stood aside so that the cart, which was massive for an indoor construct, could roll on through the corridor and into the churchs kitchen.

Morning, Mrs. Handy, Tibor said.

Ely Handy said dustily as she did not face the limbless man, Good morning, Tibor. Pax be with you and with thy saintly spark.

Pax or pox? Tibor said, and winked at Father Handy.

No answer; the woman puttered. Hate, Father Handy thought, can take marvelous exceeding attenuated forms; he all at once yearned for it direct, open and ripe and directed properly. Not this mere lack of grace, this formality he watched her get milk from the cooler.

Tibor began the difficult task of drinking coffee.

First he needed to make his cart stationary. He locked the simple brake. Then detached the selenoid-controlled relay from the ambulatory circuit and sent power from the liquid-helium battery to the manual circuit. A clean aluminum tubular extension reached out and at its terminal a six-digit gripping mechanism, each unit wired separately back through the surge-gates and to the shoulder muscles of the limbless man, groped for the empty cup; then, as Tiber saw it was still empty, he looked inquiringly.

On the stove, Ely said, meaningly smiling. So the carts brake had to be unlocked; Tibor rolled to the stove, relocked the carts brake once more via the selenoid selector-relays, and sent his manual grippers to lift the pot. The aluminum tubular extensor, armlike, brought the pot up tediously, in a near Parkinson-motion, until, finally, Tibor managed, through all the elaborate ICBM guidance components, to pour coffee into his cup.

Father Handy said, I wont join you because I had pyloric spasms last night and when I got up this morning. He felt irritable, physically. Like you, he thought, I am, although a Complete, having trouble with my body this morning: with glands and hormones. He lit a cigarette, his first of the day, tasted the loose genuine tobacco, purled, and felt much better; one chemical checked the overproduction of another, and now he seated himself at the table as Tibor, smiling cheerfully still, drank the heated-over coffee without complaint. And yet

Sometimes physical pain is a precognition of wicked things about to come, Father Handy thought, and in your case; is that it, do you know what I shallmusttell you today? No choice, because what am I, if not a man-worm who is told; who, on Tuesday, tells, but this is only one day, and just an hour of that day. Tibor, he said, wie geht es Heute?

Es geht mir gut, Tibor responded instantly.

They mutually loved their recollection and their use of German. It meant Goethe and Heine and Schiller and Kafka and Falada; both men, together, lived for this and on this. Now, since the work would soon come, it was a ritual, bordering on the sacred, a reminder of the after-daylight hours when the painting proved impossible and they couldhad tomerely talk. In the semigloom of the kerosene lanterns and the firelight, which was a bad light source; too irregular, and Tibor had complained, in his understating way, of eye fatigue. And that was a dreadful harbinger, because nowhere in the Wyoming-Utah area could a lensman be found; no refractive glasswork had been lately possible, at least as near as Father Handy knew.