Title Page

DEUS EX MACHINA

The Best Game You Never Played In Your Life

Mel Croucher

Publisher Information

Published in 2014 by

Acorn Books

www.acornbooks.co.uk

An imprint of

Andrews UK Limited

www.andrewsuk.com

The right of Mel Croucher to be identified as the author of this work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998

Copyright 2014 Mel Croucher

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Any person who does so may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Introduction

This is the story of a video game called Deus Ex Machina. Some players say it was the best computer game ever written. They reckon playing Deus Ex Machina changed their lives. It changed mine. First I wrote it, then it put me out of the business for thirty years, then it tried to kill me.

The ancients believed that everything in the heavens above and in the world down below is made up from four basic elements. Earth, air, fire and water. When it comes to the ingredients of a video game, the ancients were dead right. There are only four elements in any video game that has ever been written. And those four elements are chess, dice, ping-pong and bunkum. Every blood-soaked shoot-em-up, all swords-and-sorcery twaddle, each tedious adventure and pitiful sports simulation, everything and anything that passes for computer gaming is a combination of these elements.

Which means that the video games industry, the biggest entertainment industry the world has ever known, is founded on the same rehashed ingredients, remixed and repackaged over and over again. In which case it also means that video games players are a bunch of suckers, duped into shelling out good money for the same bad experiences. All video games are the remixed and regurgitated ingredients of the strategies of chess, the throw of the dice, the hand-eye coordination of ping-pong and the confidence trick of bunkum.

Who says so? I say so. Who am I? Im the founder of the British computer games industry. The guy who started it all. The Grand Wazoo. So as well as being the story of a video game called Deus Ex Machina, this is also the story of the founding days of the British computer entertainment industry. And, it was conceived not in a test tube, but in a pint mug.

Chapter 1

Genesis

The video games industry is the biggest money-making entertainment sector in the world. Thats apart from gambling, drugs and pornography, of course. And the British video games industry is worth billions. Its bigger than music, movies, books and magazines. And I declare that I kicked off the British video games industry at zero cost, with zero investment, zero equipment, zero experience and zero planning.

The worlds first commercial video games were mostly based on ping-pong, but it wasnt long before glowing rectangular ping-pong balls were replaced by little green space invaders, based on a mixture of ping-pong, chess and dice. Then some bright spark figured out that as well as little blobs of light, you could add tricks, and so bunkum was introduced.

So if this is the story of Deus Ex Machina , then it is essentially the story of computerised bunkum on a grand scale. Here goes then. Lets start with the conception.

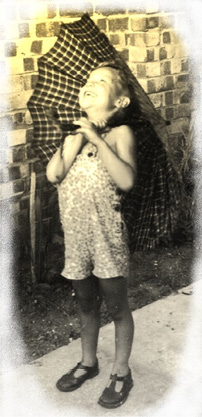

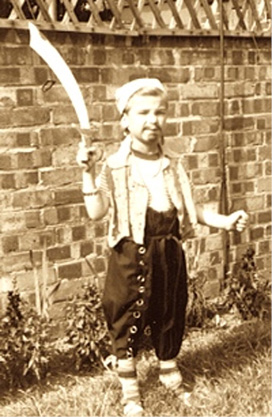

I began in the 1940s when a clever refugee from Nazi Germany met a hard-working dockyard worker with a bicycle and tuberculosis in the teeming city of Portsmouth, the home port of the British navy, and bombed to bits by the time I arrived. They fell in love, got married and had sex, although probably not in that order. But the story of The Best Game You Never Played In Your Life begins on the morning of my seventh birthday, when there was coal in the scuttle, when Winston Churchill was still running the country through a haze of alcohol and dementia, and when I programmed my first games machine. Up until then, the whole world had been in monochrome, but I can remember my seventh birthday in flickering, muted colour.

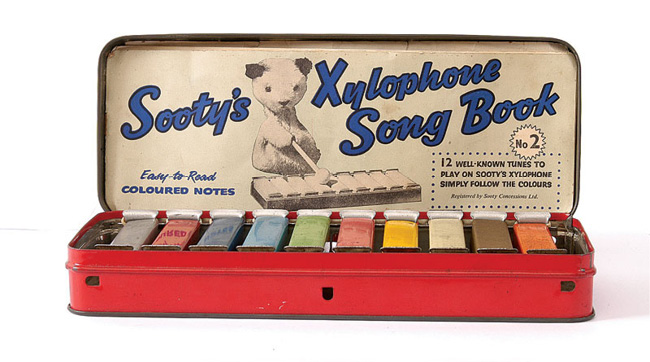

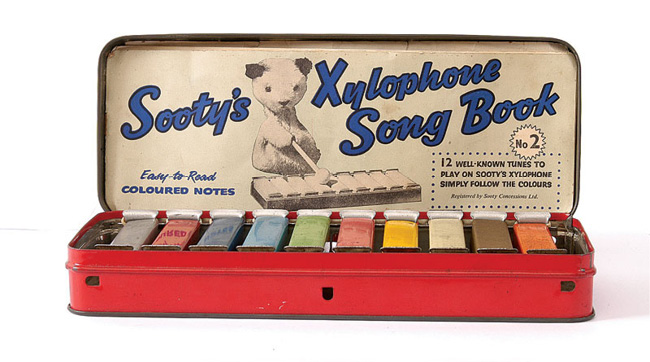

My first games machine was a dangerous little metal sequencer. It had a keyboard colour-coded in toxic lead paint, designed to stunt the growth of us post-war baby boomers. My Mum and Dad had bought me a Sooty-the-puppet Xylophone. It was a very happy birthday.

Instead of music, the Sooty Xylophone was supplied with little cards that displayed rows of coloured dots, and the idea was to bash one colour-coded key at a time in the order each dot appeared. This was supposed to result in instant musical genius, a bit like the young Mozart, but adapted for a sociopathic glove puppet. Obviously the manufacturers expected all young Mozarts to wheedle their parents for a Sooty glove puppet to go with the xylophone, because they only supplied a single bashing stick, and glove puppets can only handle one stick at a time.

The songs were child-safe and really banal, and those preprogrammed sequences soon began to bore me. Then, for the first time, I can remember thinking maybe I could change things. Maybe I could even improve things somehow by simple experimentation. So, slowly and methodically, I reordered the colour-coded xylophone keys into more interesting combinations, and wrote my own sequences of coded coloured dots. The result sounded like crappy little tin strips hit with a stick in random order, which is exactly what is was. And although it was programming of a sort, I gave up computing in favour of the yo-yo well before my next birthday.

The story begins again a few years later, with a pianola that lived behind the kitchen in a little two-up, two-down terrace house, with an outdoor thunderbox and no bathroom. Pianolas were a sort of giant mechanical iPod for Victorians who didnt have the talent to play regular pianos, and they were very popular in the nineteenth century. By the time I tackled this ancient Aeolian upright grand model, the world was listening to music on the wireless, and pianolas were very unpopular indeed. In fact they were so unpopular that most of them had rotted. This was because the firmware that powered the keys was a matrix of rubber tubes which time had hardened and fractured like dead macaroni, so it wheezed like my Dad in the mornings. But the software that called the tunes was great. It was stored as holes punched into rolls of paper that tore and decomposed in sync with the British Empire. The grand old pianola was, of course, my first properly programmable computer.

That summer I had a square-ended metal hole-punch nicked from the Dockyard by my Dad, and acne. So I spent it in hiding, humiliating the pianola and forcing it to perform lewd acts of a musical nature.

Next page