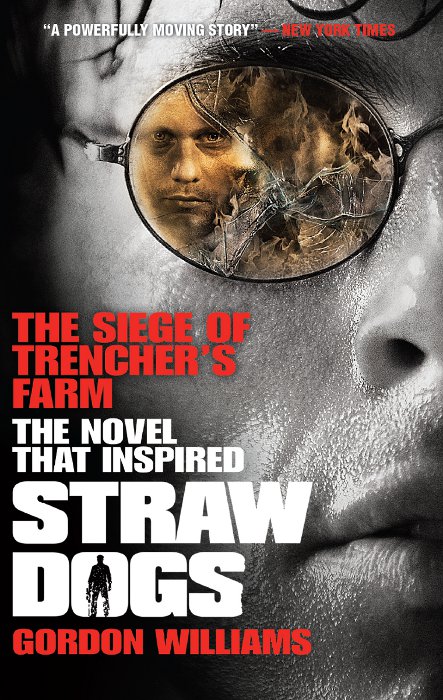

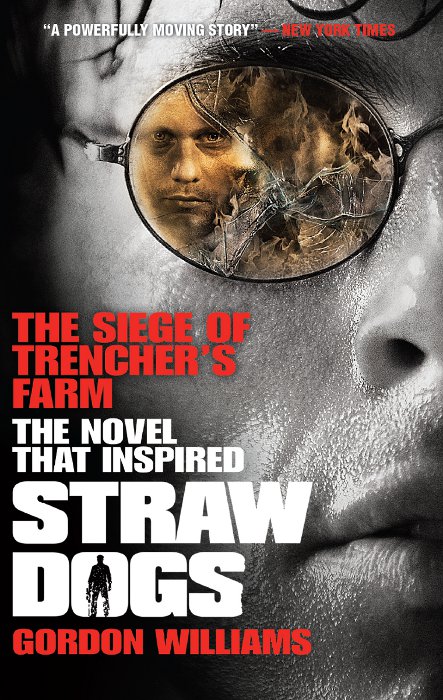

THE SIEGE OF TRENCHERS FARM

THE NOVEL THAT INSPIRED

STRAW DOGS

GORDON WILLIAMS

TITAN BOOKS

THE SIEGE OF TRENCHERS FARM

Print edition ISBN: 9780857681195

E-book ISBN: 9780857683021

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: August 2011

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Gordon Williams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright 1969, 2011 by Gordon Williams.

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: , or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the USA.

To Peter Morgan

ONE

In the same year that Man first flew to the Moon and the last American soldier left Vietnam there were still corners of England where lived men and women who had never travelled more than fifteen miles from their own homes. They had spent all their lives on the same land that had supported their fathers and grandfathers and great-grandfathers and unknown generations before that.

The neighbouring parishes of Dando and Compton Wakley formed such a place. Here, in the same generation that produced men who looked back at Earth from the blackness of outer space, existed Englishmen to whom the two hundred mile journey to London was an almost legendary experience, something that might happen once in a lifetime, if at all.

Progress had brought only superficial change to the life of Dando. Farmhouses built three and four hundred years ago, when walls were made by trampling mud and straw, now bore television aerials on their chimneys. Horses had given way to tractors. The narrow roads of the parishes, their banks so high they were little better than tunnels with an open roof, now had metalled surfaces and at night the jinking lantern on the shaft of a wooden cart had been replaced by the low-angled searchlight sweep of motor-car headlamps. The children of the district no longer had to walk six or seven miles to and from the primary school at Compton Wakley; instead they were collected in the morning by a single-decker bus paid for by the County Education Committee and brought back home in the evening.

Ancient inns to which farming men, generations of them, had walked three and four miles in the dark, after twelve hours toil in the fields, now sold mass-produced beer brought by lorries from the cities.

Yet these changes were akin to the crippled wing which a hen plover drags over grass when man or beast approaches her nest. They were a disguise behind which the old ways and the old ideas lived on as before.

The face of the short, squat man with the black hair on the tractor seat was identical to the face of the man who had worked the same ground a thousand years ago.

At dusk on an autumn evening when the sky was a deep blue canvas smeared by fingers of flame cast by a burning sun, when haunting mists crept down from the dark hills of the moor, it was possible to stand by a wooden gate and look over fields and hedges and woods and see a farmhouse light winking across a shadowy valley and to think... of the men who had lived here before, of rough-clad armies coming over the bare brows of those same hills, of the savage fair-haired men who came from the sea, of kings and nobles on panoplied horses...

Also at night, in the dim light thrown by a single, cobwebby electric bulb over the encrusted walls of a barn corner, it was possible to stand on a hard earth floor and drink cold, bitter cider drawn from mighty black barrels made by long-dead coopers who had talked among themselves of Napoleon Bonaparte. The tongues of the men who drank the cider were as strange to the outside ear as the dialects of foreign jungles. The names of the men were names that were written in the Conquerors Domesday Book, the same names that had lived on the same farms since Drake sailed from Plymouth to smash the might of Spain.

Some of these men, it is true, had gone away from Dando to fight in the last war, the modern war. They had fought in African deserts and Burmese jungles and Italian mud. Yet, unlike the city men, they had come home determined to maintain the old ways, as though the modern civilisation they had seen was an alien land from which they had escaped. Some of these men who drank cider in the year of the moon rockets could not read or write: Some, if a stranger were present, could adopt the speech of the cities. Some could not.

And some who could, would not. For there was a dark side to this corner of England. Cut off from the rest of that side of the country by low hills and served by roads no wider than a single motor car, the farmers and villagers had over the years come to regard themselves more and more as being apart from other people. Geography was one reason for the isolation of the two parishes. Poverty was another. The land here was poor. The men, whether they owned the land or worked for someone else, had to spend long, dreary days in the fields. Few of them could afford to go away to seaside towns for holidays and neither did outsiders come to Dando, for it was not a city mans idea of beautiful countryside. To the south and west lay the Moor. It, they said, had a climate all its own, a meeting point for cold rain-winds from the Atlantic Ocean. On the edge of the Moor, standing as it were between Dando and the sun, was the great bulk of Torn Hill. Even in summer Torn seemed to cast a shadow over the two parishes, robbing them of warmth.

So the outside world tended to pass Dando by. And Dando people, either from pride or fear if the two are divisible preferred to stay within the boundaries of their own parishes, to be born there, raised there, wed there, and buried there. It was said that some of the older people, especially the women, could give a family connection between almost any two individuals in the area.

Dando marries its own, was a local saying. In neighbouring towns this was often accompanied by knowing looks and the shaking of heads. Dando, they said, had married its own for too many years. And no closed family could be without its dark secrets. The few outsiders who did buy land within the boundaries of the two parishes might spend a lifetime without hearing these secrets, for some things could not be told to strangers and a stranger could be any man whose father had not been born in the parish.

The outsider might hear hinted references to things he did not understand. He might ask, for instance, why a certain pasture behind the woods which stood above the village of Dando Monachorum was called Soldiers Field. He would be told that ancient history had it that a soldier was once murdered there. He would not be told that there was one old man still in the village who had been in the field the night the soldiers head was hacked from his body by a hedge-cutters billhook. He would not be told that there were men and women who could remember their fathers being out that night, when the soldier came from the barracks at Plymouth and met twelve-year-old Mary Tremaine on the road from the ford at Fourways Cross... and how the men came from farmhouses and cottages and the Dando Inn when the soldier a deserter, a man of some strength who had crossed the Moor on foot was caught. Only the men who were there could tell what was in their minds as they slew the soldier, each man taking his turn with the billhook so that all would have taken part.

Next page

![George Wallace - Hunter Killer [Movie Tie-In]](/uploads/posts/book/848976/thumbs/george-wallace-hunter-killer-movie-tie-in.jpg)