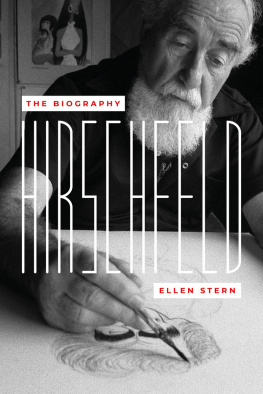

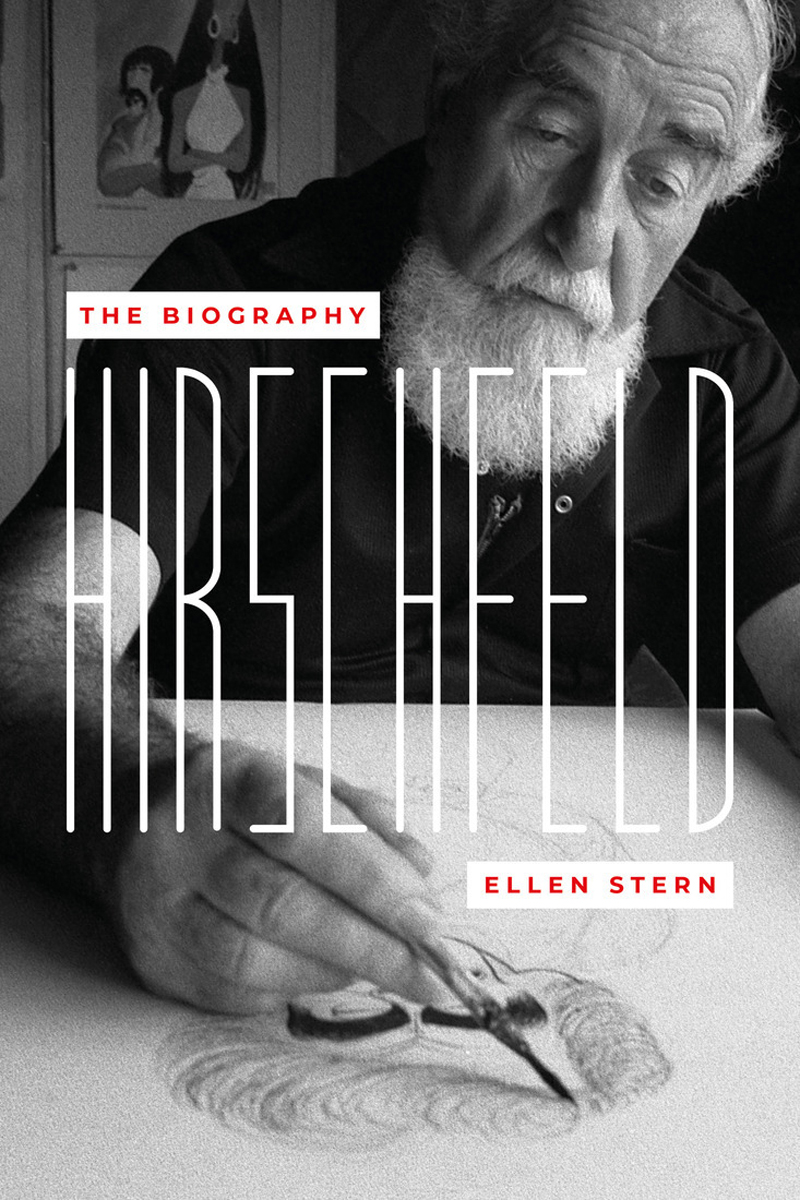

Also by Ellen Stern

Best Bets

The Very Best from Hallmark

Once Upon a Telephone

Sister Sets (coauthor)

Threads (coauthor)

Gracie Mansion

Copyright 2021 by Ellen Stern

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by media5designs

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2962-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-5941-1

Printed in the United States of America

For Peter

If you live long enough, everything happens.

Al Hirschfeld

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

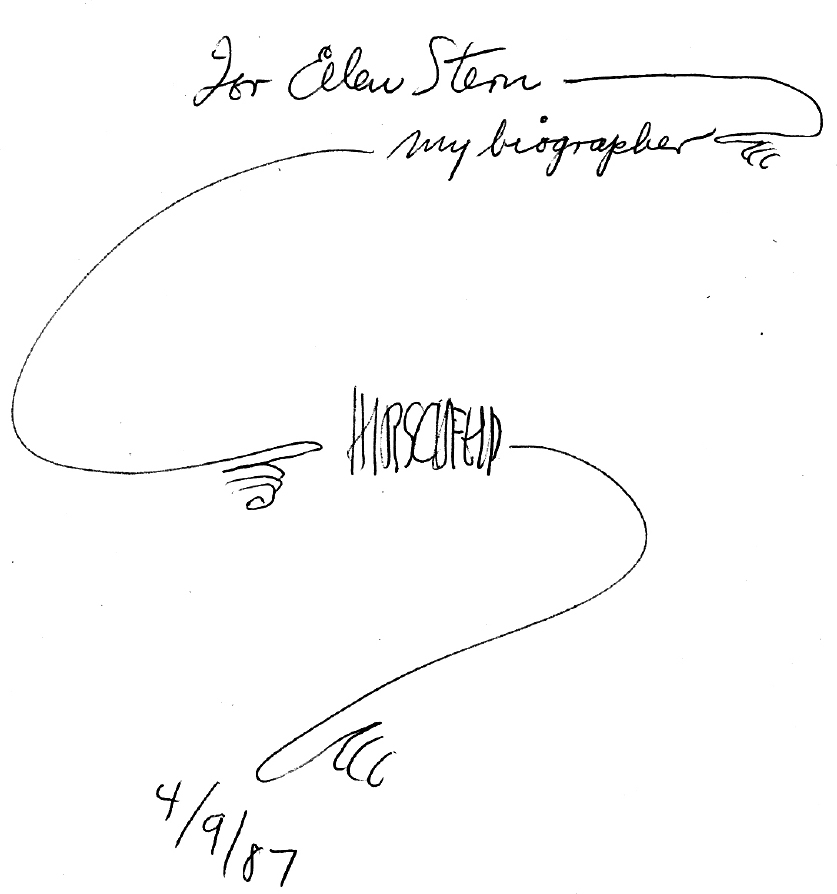

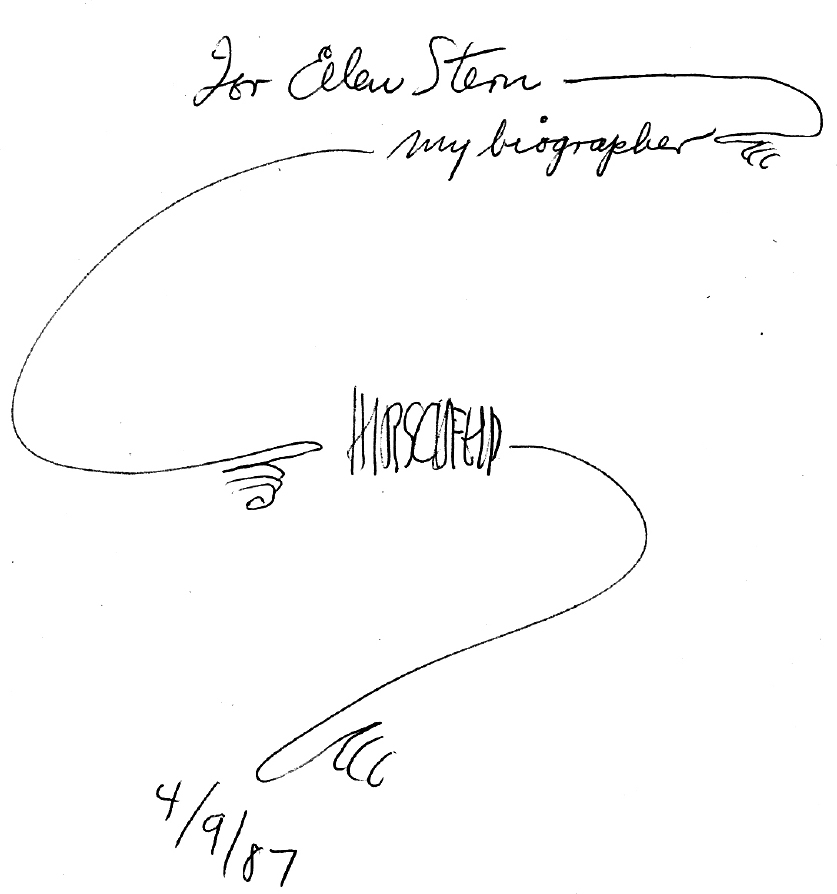

In 1987, I interviewed Al Hirschfeld for GQ magazine. The profile ran, he liked it, and that was that. We never saw each other again. But I held on to my notes.

In 2011, when his widow sold the townhouse where hed lived, worked, and hosted so many starry soirees, I rediscovered the copy of his book Show Business Is No Business that Id asked him to inscribe that afternoon twenty-four years before. This is what hed written:

So here goes.

AT THE TOP

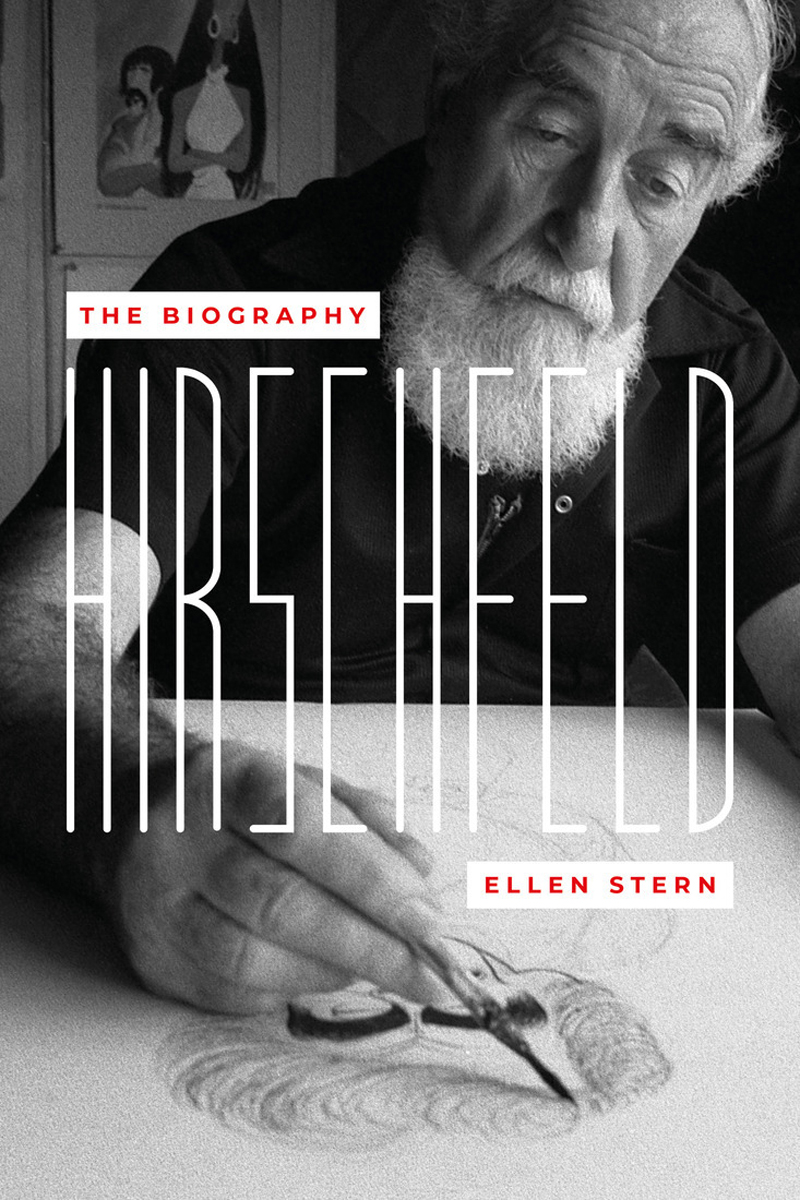

On the fourth floor of his Ninety-fifth Street townhouse, a bearded fellow is in a barber chair. Perched on two small pillows and a torn green leather cushion, his slippered tootsies parked on an iron footrest supported by two phone books, the artist is at work. This is his studio. It is where he does several drawings a week, several hundred a year, ten thousand in a lifetime. It is his refuge when things go right and things go wrong. I spend most of my time here, he says. I just visit downstairs.

Attired in his blue jumpsuit, Al Hirschfeld ponders the product before him: a pencil sketch of Merman, Mostel, or Bernstein that will, when he puts ink to it, capture the essence of Merman, Mostel, or Bernstein fit to print in The New York Times , the Herald Tribune , TV Guide , Vanity Fair , the Brooklyn Daily Eagle , The American Mercury , or Seventeen . The swirls, the curls, the ginger, the bounce!

The windowsill is a garden of dusty plants, and the linoleum floor is cracked, but the room is in deliberate disarray. He knows whereamong the bookshelves, mountains of drawings, mounds of reference materials, piles of magazines, tubes and boxes and envelopesthings are. The green walls are tacked and taped with the unfinished sketches, drawings, and posters he keeps close (Anita Ellis in the spotlight, Sonny and Cher in color, George Burns, Pavarotti) and signs: TOW-AWAY ZONE NO PARKING... VIETATO FUMARE... REMEMBER: IT WAS AN ACTOR THAT KILLED LINCOLN. The bulletin board is festooned with yellowed clippings, letters, snapshots, and cartoons.

The slanted top of the old oak drafting table, picked up at an auction years ago, is scarred by years of slicing his own triple-ply, cold-pressed illustration boards before he started having them custom-cut. No matter the size of the published drawing, the original is done on a board measuring twenty-one by twenty-seven inches. Antique wooden boxes contain the Gillott crow-quill pens and Venus B pencils, rulers and knives, electric eraser. Jars of Higgins black India ink share the space with brushes in glasses, cans, and jars, while others dangle dancingly from hooks. Hirschfeld draws by daylight, skylight, and a lamp over his headrelic of a Cincinnati department store and installed by his friend Abe Feder. The phone is close at hand, since hes listed in the book and grabs it when it rings.

The Koken barber chair, a product of St. Louis, entered the scene in the 1930s. He considers it the most functional chair in the land. It goes up and down, it turns around, it becomes a chaise longue, he says. Lee Shubert, who kept a barber chair in the office so he could be shaved twice a day, used his for a nap. Sweeney Todd, on the other hand, used his for Stephen Sondheim.

A crony will flop on the couch to schmooze, but outsiders take the captains chair with its time-worn blue cushion. These are the sitters, here to be immortalized. Unlike the stars of stage, screen, and bandstand he observes in their own habitats, these are the designers, composers, and orthopedists who come to be Hirschfelded on their own dime.

Theyre disappointed. They expected communion. For them, the encounter is history; for Hirschfeld, its business. Hes genial but brisk, attentive but uncommunicative. The visit goes too fast, allows too little. Al simply looked at my father, did a couple of squiggles, then took the paper and turned it over. Thats all I saw him do, says Ted Chapin, recalling the day he accompanied his father, Schuyler Chapin, New Yorks former commissioner of cultural affairs, to be drawn. From squiggles to immortality, just like that.

I thought he was going to sketch me when I went up there, says the Broadway lyricist Sheldon Harnick, and I was surprised that instead of that he took Polaroids.

Is there anything in particular youd like me to do? Do I sit in a certain way? the composer Maury Yeston asks. Oh, no, absolutely not, says Hirschfeld. We just have a conversation and I do my work.

To be welcome in this sanctum, so close to the artist who has illustrated Broadway so well for so long, is an honor in itself. To be seen by the eyes and sketched by the hand of the man who has drawn so many hotshots and hambones is intoxicating. A Tony is swell. A Hirschfeld is better.

MEET HIM IN ST. LOUIS

He first appears on a Sunday, as well he should.

June 21 is the first day of summer, the longest day of the year, and the date most often assigned to A Midsummer Nights Dream. But the setting of Al Hirschfelds birth is no bank where the wild thyme blows, where oxlips and the nodding violet grows. Its a steamy back bedroom in St. Louis.

Blocks away from the two-family brick house on Evans Avenue, preparations are relentlessly underway for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, originally scheduled to open this year but nowhere near ready, no matter how much pomp attended Teddy Roosevelts dedication in May. It is 1903.

While the St. Louis Post-Dispatch boasts of exposing corruption at the post office, the Globe-Democrat offers a solution for overcrowded trains, and the Republic glorifies a dead cardinal, a sweating midwife brings forth the Hirschfelds boy. While East St. Louis, across the river, remains awash after a mud levee slid into the Mississippi two weeks ago, baby Albert slides into the world and is swaddled.

Next page