Also by John Lewis-Stempel

Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field

The Secret Life of the Owl

The Wildlife Garden

Foraging: The Essential Guide

Fatherhood: An Anthology

The Autobiography of the British Soldier

England: The Autobiography

The Wild Life: A Year of Living on Wild Food

Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War

The War Behind the Wire: Life, Death and Heroism Amongst British Prisoners of War, 191418

The Running Hare: The Secret Life of Farmland

Where Poppies Blow: The British Soldier, Nature, the Great War

The Wood: The Life and Times of Cockshutt Wood

Still Water: The Deep Life of the Pond

The Glorious Life of the Oak

The Wild Life of the Fox

The Private Life of the Hare

John Lewis-Stempel

WOODSTON

The Biography of an English Farm

TRANSWORLD

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Doubleday

Copyright John Lewis-Stempel 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover art direction by Beci Kelly/TW

Cover illustration: James Weston-Lewis

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

ISBN: 978-1-473-55860-1

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Modern history has been much too sparing in its prose pictures of pastoral life. A great general or statesman has never lacked the love of a biographer; but the thoughts and labours of men who lived remote from cities, and silently built up an improved race of sheep or cattle, whose influence was to be felt in every market, have no adequate record.

H. H. Dixon (18691953)

On English ground

You understand the letter, ere the fall,

How Adam lived in a garden. All the fields

Are tied up fast with hedges, nosegay-like;

The hills are crumpled plains, the plains, parterres,

The trees, round, woolly, ready to be clipped;

And if you seek for any wilderness

You find, at best, a park. A nature tamed

And grown domestic like a barn-door fowl,

Which does not awe you with its claws and beak,

Nor tempt you to an eyrie too high up,

But which, in cackling, sets you thinking of

Your eggs to-morrow at breakfast, in the pause

Of finer meditation.

From Aurora Leigh, Elizabeth Barrett Browning (180661)

Prologue

Et in Arcadia Ego

A dedication to Joe and Margaret Amos

T HE GRAVEYARD IS SHROUDED in mist from the river.

Ive come here to meet people I cannot see, but the mist is blameless. My people are long dead.

In the dark tower of a yew tree a wren tisks its alarm call, as regular as the counting of clocks. Further away, in a vague fir, a robin sings an autumn hymn, muffled and melancholic.

Then, there they are: Percival Amos and Margaret Amos, their names inscribed in black on a grey marble headstone. The roots of the fir have tilted the stone; ivy clutches at it. Clagged with damp, their memorial needs a wipe of my coat sleeve for their names to shine.

I loved my maternal grandparents, and not just because they cared for me during tranches of my childhood, but also for what they were. They were the people of Thomas Grays Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard:

Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke;

How jocund did they drive their team afield!

How bowd the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

Percival known to everyone as Joe and Margaret Amos were yeoman farmers, salt of the earth, the backbone of England. My grandmothers ancestors fought at Agincourt as men-at-arms; they were hard people, hard like the Herefordshire mountain they kept their sheep on.

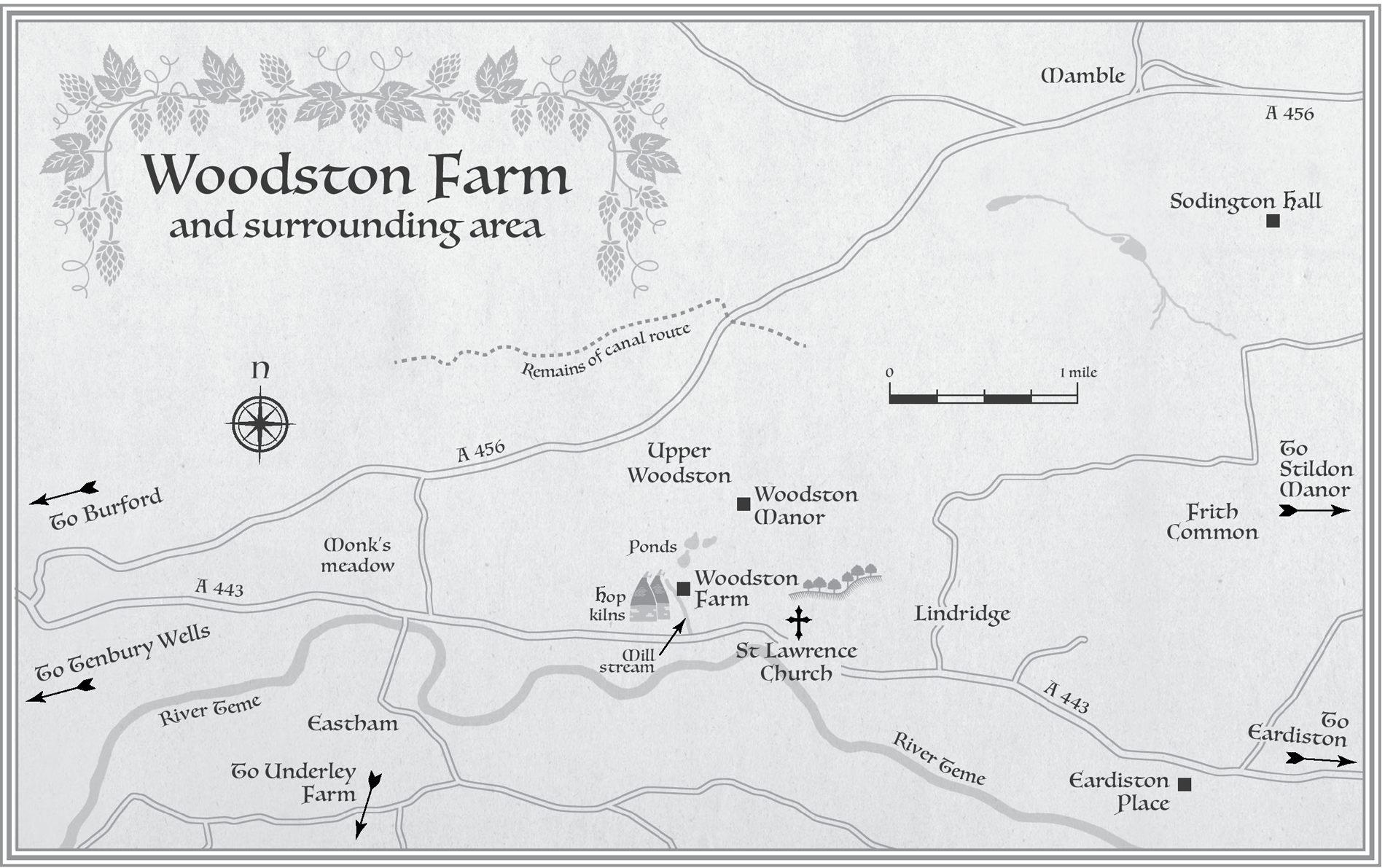

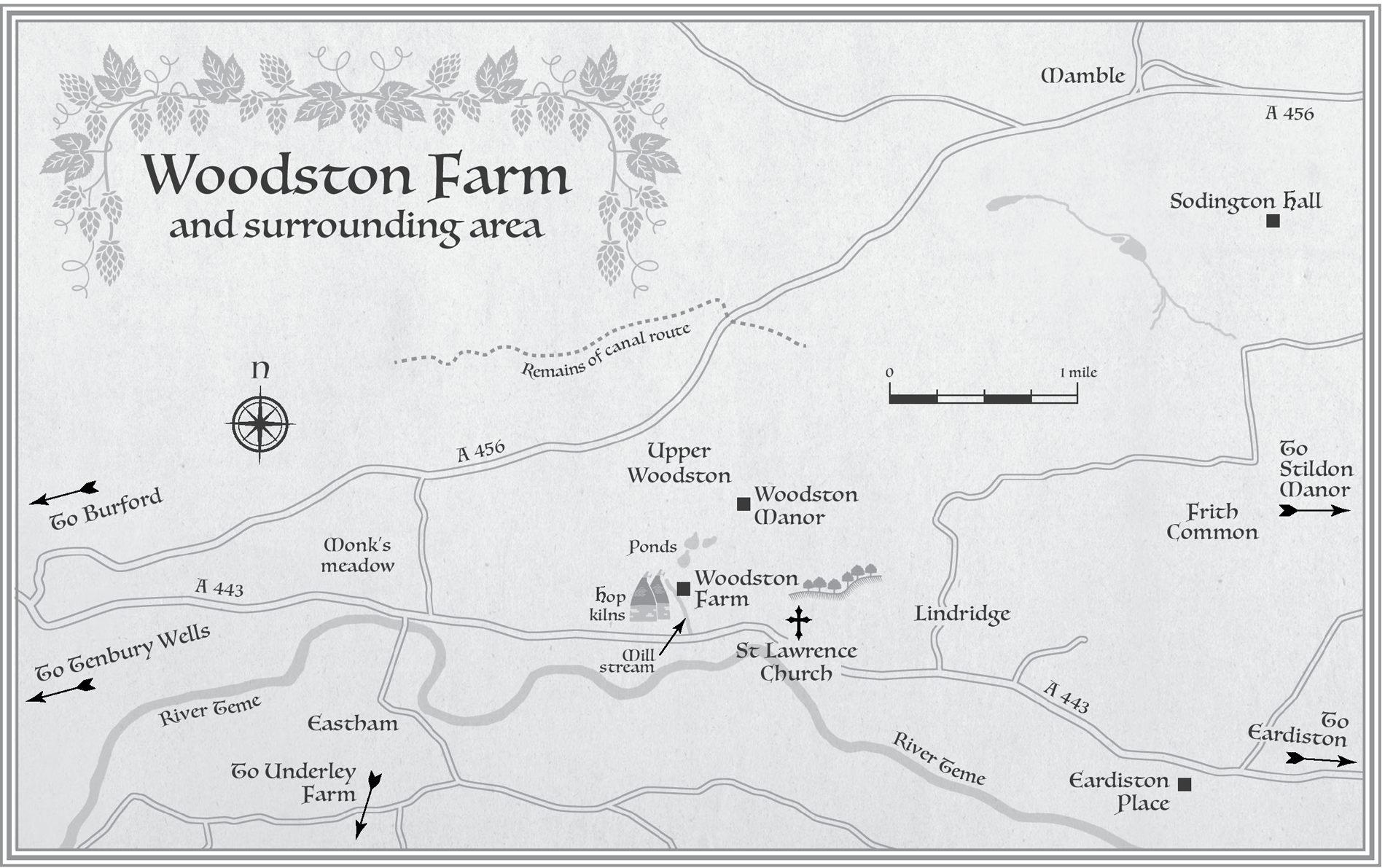

For most of their adult lives they married in their early twenties Joe and Marg were tenant farmers, of hops, and for a decade or more farmed up the lane from here at Lindridge.

Time flies; ivy grows. My duty this morning is the pulling away of the evergreen parasitic tendrils.

I was last here in this churchyard beside the River Teme in the long hot summer. It was midday in late June, and a young guy in a baseball cap was varnishing a bench, encouraged by his girlfriend and her radio, though this was turned down reverently; a wood pigeon was roo-cooing in the heat, soft and somnolent. It was peaceful, and it was beautiful too. Bounded by the sparkling Teme and a row of red-brick cottages, St Marys in Tenbury Wells, Worcestershire, is the perfect English graveyard.

That day in June, with not a cloud in the sky, the sun blinded off the weathervane, a gold cross, on the Norman steeple. A sparrow flew to its nest, a hole in the stone of the nave. Swallows plastered their cup-home on an oak beam in the porch. The church gave both birds refuge.

The grass was full of flowers as I wandered down between the gravestones. Ox-eye daisy, borage, white clover, dandelion, meadow vetch.

In almost every floral-coloured aisle, an echo of a name gone now, a call on conscience and memory. Lambleys. Wilcocks. Yarnolds.

Kin.

Cabbage-white and meadow-brown butterflies blatted about in the silent air, indecisive, before settling on the lilac. There were mason bees, and the elders fruits were green and vital.

Odd, is it not, that to see living things today one often needs to visit the place of the dead? The churchyard of St Marys is Gods Acre. Today, in the great white peace of an October morning, a single thrush starts singing matins in the yew behind the nave.

Im not sure how old the yew trees of St Marys graveyard are. Taxus baccata can live for thousands of years. But I do know they have seen generations of my family come into this life, leave it. When I see the yews they recall to mind always four particular lines from Grays Elegy: