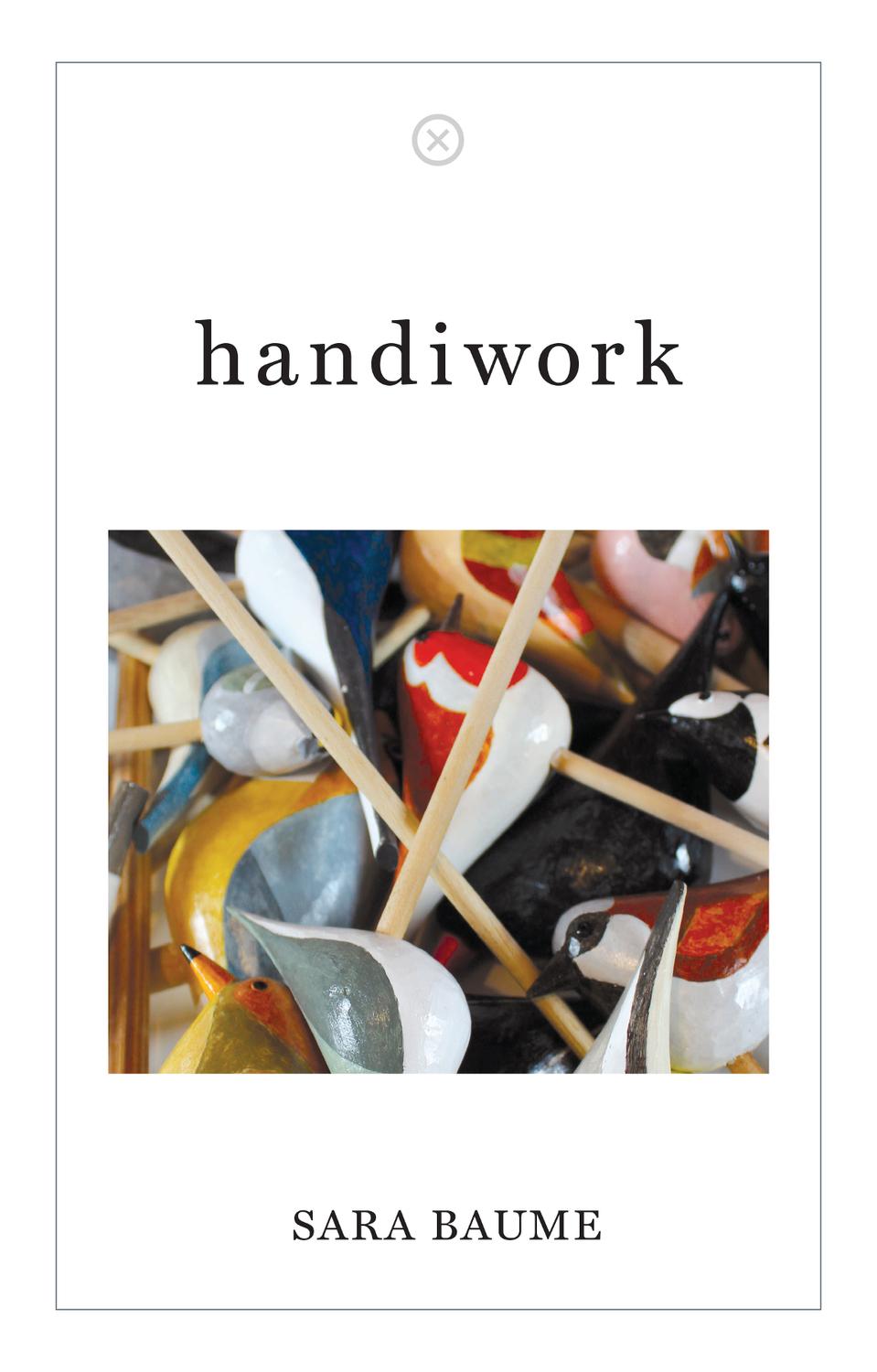

Sara Baume - Handiwork

Here you can read online Sara Baume - Handiwork full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Handiwork

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Handiwork: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Handiwork" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Handiwork — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Handiwork" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

for Dad

AMATEURS, STEPHEN KNOTT writes in Amateur Craft: History and Theory, have their own convoluted, inefficient and superfluous processes of production that reflect their subjectivity and freedom from the obligation to produce a defined output.

THERE IS AN ALASKAN SONGBIRD , the northern wheatear. She weighs about as much as a small ball of wool, and every autumn she flies about as far as 300,000 balls of wool unspooled in a westerly direction, disentangled across Siberia and Kazakhstan and Iraq and Saudi Arabia, finally coming to a definitive stop in East Africa. It takes her three months to get there and two-and-a-half months to get back again, and so the northern wheatear devotes almost half of every year to these journeys which she makes out of countless individual flaps beating her wings continuously against winds prevailing and preternatural over the course of 30,000 kilometres of sky.

There are easier routes she could take; there are places with clement climates far closer to Alaska than sub-Saharan Africa, but the northern wheatear doesnt choose them; she doesnt choose at all.

Every autumn, she follows the route her ancestors initiated at the end of the last Ice Age, 10,000 years ago the convoluted, inefficient, superfluous directions that are her genetic inheritance.

And then, in spring, she goes the same way back again.

I HEAR THE STORY of the northern wheatear on a day in spring, from a podcast which I listen to sitting in the straight-backed chair at the eastern end of the living room table. I sit there every day between the hours of twelve and four, parallel to the windowsill and overshadowed by a row of books, a Christmas cactus, and a dusty globe which encapsulates a long-expired lightbulb. When I retell a version of the story of the journey of the northern wheatear to Mark, later in the evening a slightly erroneous, airily embellished version he remarks that there are fish who swim against the current salmon and herring who live in the open sea but are compelled to travel back to the rivers and streams in which they were born in order to spawn and this gives me cause to remember a tiny goldfish I owned for a year or so in my early twenties who, on the occasion of having her water changed, would make every effort to resist being poured from a corner of her narrow tank into a giant mayonnaise jar.

The goldfish would go to the place where the last of the water pooled as the glass was lifted. She would turn her face to point in the opposite direction of the tilt. She would push against the force of gravity and the flow of water, wriggling her entire body, as if burrowing upwards through thick soil.

THE WORKSHOP IS the craftsmans home, Richard Sennett writes in The Craftsman. Traditionally this was literally so. In the Middle Ages craftsmen slept, ate, and raised their children in the places where they worked.

THIS HOUSE is a house of industry.

It has four bedrooms, only one of which is devoted to sleep.

THE STRAIGHT-BACKED CHAIR at the eastern end of the living room table, parallel to the windowsill and its clutter, is one of several workstations dispersed between rooms, starting outside the back door with the rusted yard tap and extending all the way through to the weatherworn garden bench.

THE SHORT STRETCH of countertop alongside the kitchen sink is a mixing station. Theres a sack of modelling plaster and a stack of plastic containers rescued from the recycling bin the tall, round pots of yoghurt and the flimsy trays of rectangular biscuits fig rolls, malted milks, custard creams. Theres a porcelain scoop for measuring the correct ratio of plaster to water, and a tall-stemmed teaspoon for whisking the powdery lumps away. Wet plaster must be creamy. Once poured, I bump the base of the mould gently against the surface of the countertop in order to hustle any residual air to the surface, to set it free. Tiny bubbles obligingly rise and burst a stippled pattern of negative space appears.

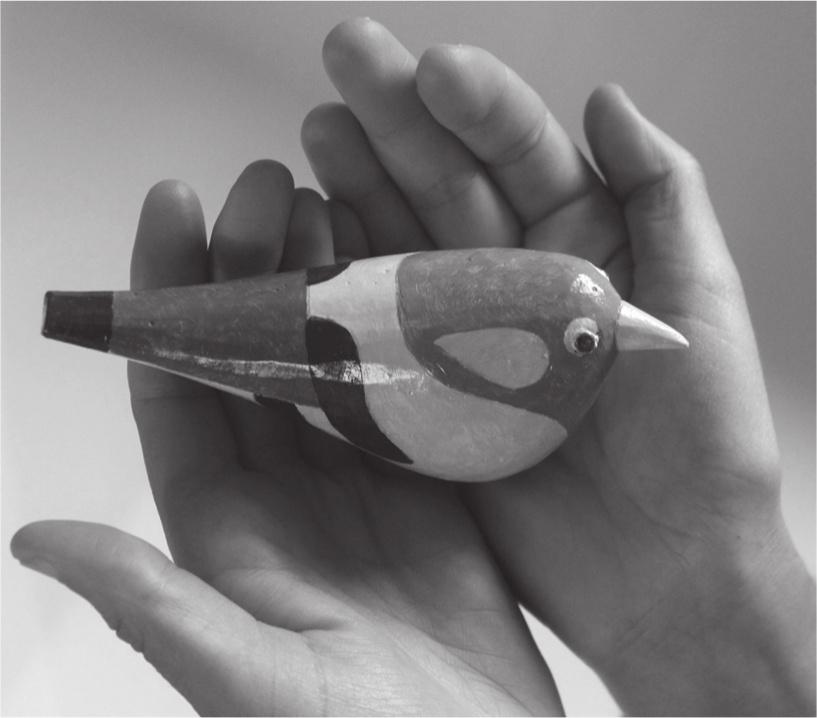

A SIGNIFICANT PATCH of floor in front of the unused hearth in what would have traditionally been the good front room and which is now the guest bedroom is a sawing station. A miniature scroll saw trails from a socket and sits on a mat of shaped foam. Adjacent to the saws table, theres just enough space for me to kneel before it as I work a person-sized circle cleared in the sand-coloured dust. Behind the clearing and the saw, theres a box of cuts and offcuts balsa and ply, pine dowels and cherrywood lathes. Strewn about the lino and the rag-rugs, theres sandpaper of varying grits from course to fine and from unfolded to extensively folded.

THE LOW COFFEE TABLE in front of the sofa, which faces the log stove and the TV set, is a painting station. A glass jar of brushes is permanently accompanied by another of cloudy water, and a ball of clotted kitchen roll. The ferrules of the brushes are narrow and wide, rounded and straight; the bristles are natural and synthetic, soft and rough, filbert and fanned. I only ever use the same three, the plainest three, but I keep them all because I am constantly susceptible to future projects to the possibility that some day I might be confronted with a surface that requires a more exotic class of stroke. Beneath the table, on top of a large tub of white emulsion, theres a dish of contorted tubes of acrylic paint and a thickly blotched palette in a ziplock bag.

THIS IS THE STATION where each evening comes to an end. I spend its final three hours cross-legged on the sofa; the same cushion I use as a tray to eat my dinner off becomes a platform upon which to apply paint to a succession of small objects after dinner has been eaten. The television flickers and I listen to it. In most cases, a story can be followed from sound alone, but I glance up every now and again in order to identify speakers, in order to maintain some kind of visual momentum through each programme. At dinnertime, a drinking vessel is added to the other glasses on the low coffee table and so it often happens, as the evening wears on, that I plop a sullied brush into the clear water, or take a thoughtless sip of the paint-tainted stuff.

AS EACH WORKING DAY ends on the sofa, it starts upstairs on the swivelling office chair in front of my writing desk. During the course of an ordinary day, between the swivel chair and the sofa cushions, I shift from station to station according to the hours demands, returning most predictably to the eastern end of the table in the living room.

There, in the nook beneath the windowsill, I keep a narrow timber box of knives. Inside, there are several handles and an assortment of steel blades flat, pointed, curved, tapered, some sharp and some blunt but most at some stop along the trajectory of decline from mint to spent, unused to overused.

It is important to differentiate between sharpnesses. The sharpness of each blade dictates the pressure applied by my carving hand, the speed and ease at which each shuck of set plaster slips away from its block and into crumb. Between the surface of the table and the knife box and the plaster blocks and the crumb pile, theres a sheath of old newspapers positioned to protect the table-top, even though theres already a jagged tear in the cotton and a tracery of stab marks in the vinyl.

Somehow I never manage to remember to place down a protective layer until after some initial damage has been done.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Handiwork»

Look at similar books to Handiwork. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Handiwork and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.