2012 will be a year memorable for a British diamond jubilee, a British Olympic Games, and the commemoration of the countrys greatest novelist. How best to approach Charles Dickens? There may be readers who, like the boa-constrictor and the goat, can swallow Dickens whole. I personally have known only three: Philip Collins (who taught me as an undergraduate), K.J. Fielding (who supervised my PhD) and Michael Slater (a colleague at the University of London).

I admire the work of these scholars and I have used it (gratefully). But it seems to me that there is another approach, and one that is more appropriate to that peculiarity of the Dickensian genius: its infinite variety and downright oddness. When I think of Dickens I do not see a literary monument, but an Old Curiosity Shop, stuffed with surprising things: what the Germans call a Wunderkammer a chamber of wonders.

This book, taking as its starting point 100 words with a particular Dickensian flavour and relevance, is a tour round the curiosities, from the persistent smudged fingerprint picked up in the blacking factory in which Dickens suffered as a little boy to the nightmares he suffered from his unwise visit at feeding time to the snake-room of London Zoo.

One of the wonderful things about this wonderful author is that, like Shakespeare, there can never be any final explanations, or readings. Merely an inexhaustible fund of entertainment or, as Sleary the circus master (see the first entry) would call it, amuthement. The Great Entertainer one Gradgrindian critic (F.R. Leavis) called him, intending belittlement. I see it as a term of the highest literary praise.

Dickens will sell more copies of his fiction in 2012 than he did in any year of his life and I would bet any year since his death. To pick up any of his novels, and turn any of the pages, is to understand why. He entertains. So, I hope, will what follows.

Amuthement

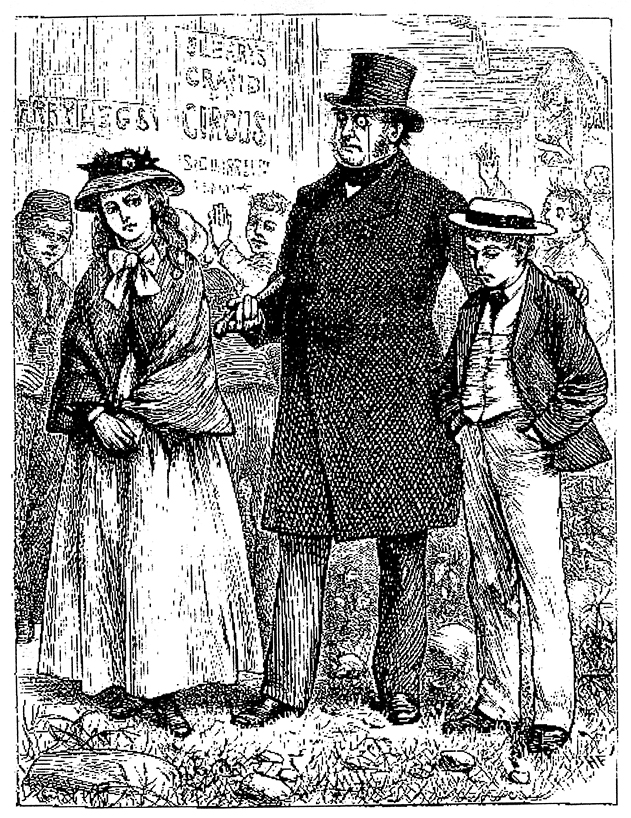

In Hard Times the lisping circus-owner Sleary repeats, like a parrot with Tourettes syndrome (an epidemic condition in Dickenss fiction), his rule of life: People mutht be amuthed. Sleary, in terms of his narrative presence, is very much a peripheral figure, but on the subject of the human need for something other than pedagogic instruction he has full Dickensian authority.

Hard Times is what the Victorians called a Social Problem Novel, centred on the wholly unamusing Preston mill-workers strike of 1854. Dickens locates Prestons social problem as originating in what Carlyle called cash nexus: the belief that the only bond between mill-owner and mill-hand was the money that passed between them. This hard-nosed hard-headedness (hard-heartedness?) Dickens associated with the Manchester school of economics Utilitarianism.

Economists scorn Dickenss amateurish grasp of their dismal science. But where amuthement was concerned he was expert. Utilitarianism, he felt, was anti-life. It did to human existence what maps do to landscape. Its exemplified in Bitzers disintegrated definition of a horse (hes the prize-pupil in Thomas Gradgrinds school).

Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring; in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, but requiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth.

The 1850s, when Dickens serialised Hard Times in his weekly paper, Household Words, saw an explosion in the travelling circus. They specialised in clever canines and trick equestrianism the original horse and pony show. The big ones might even have elephants. Dickens alludes to the wondrous jumbo in his description of the great factory in Preston (Coketown) where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness. How, one shudderingly wonders, would Bitzer describe that quadruped?

Hard Times opens in a schoolroom with Gradgrind laying down his educational theory: Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. To which Dickens responds: What about Fiction?

Mr Gradgrind objects sternly to the circus.

A few months before the great strike, Manchester opened the countrys first free public library. But what to put in it? The utilitarian authorities decreed Gradgrindish factuality. No, insisted Dickens. Fiction should also feature prominently on those library shelves (he, too, was a trade-unionist of kinds: just like those mill-workers). His plea was borne out by the first statistics (Manchester loved what Cissy Jupe calls stutterings). The most popular book borrowed from the library was The Arabian Nights. Dickens refers to it frequently in his novel.

Point proved by Sinbad the Sailor and Jumbo the Pachyderm. People mutht be amuthed. But it would, alas, be some years before the Manchester Public Library stocked the work of that most amusing of writers, Boz.

Architectooralooral

Every reader of Great Expectations laughs at the above malapropism. Joe Gargery, the blacksmith with muscles of iron and a heart of gold, has come up to London his first visit, we apprehend. He calls on Pip, now well on the way to becoming an arrant snob. Have you seen anything of London, yet? asks Pips housemate, Herbert. Why, yes, Sir, replies Joe,

me and Wopsle went off straight to look at the Blacking Wareus. But we didnt find that it come up to its likeness in the red bills at the shop doors; which I meantersay, added Joe, in an explanatory manner, as it is there drawd too architectooralooral.