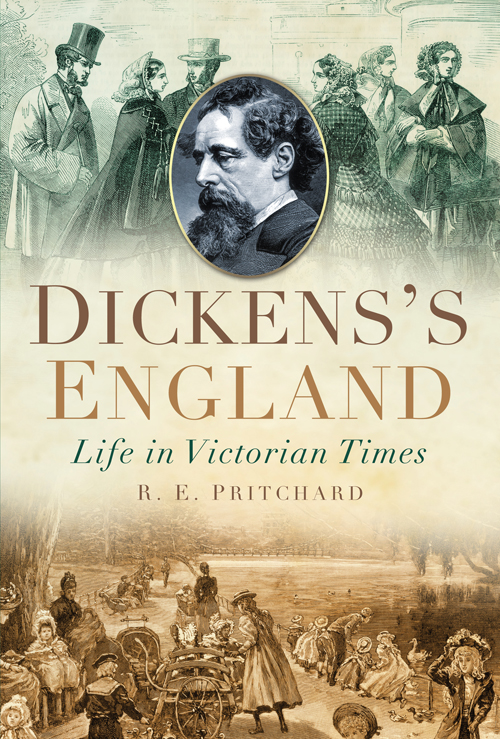

DICKENSS

ENGLAND

Life in Victorian Times

EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY

R. E. PRITCHARD

First published in 2002

This edition first published in 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

R.E. Pritchard, 2002, 2009, 2011

The right of R.E. Pritchard, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7554 7

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7553 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

Ebook compilation by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

Contents

Acknowledgements

Extracts from Kilverts Diary, ed. William Plomer, published by Jonathan Cape, by permission of the Random House Group Ltd. Extracts from Diary of William Tayler, Footman, ed. Dorothy Wise, by permission of the City of Westminster Archives Centre.

Introduction

It is impossible to put the world in a nutshell... we have selected the most striking types, the most completely representative scenes, and the most picturesque features.

Blanchard Jerrold, London: A Pilgrimage (1872)

I f Victorian London was too much for Jerrold and Gustave Dor to cope with, the England of Dickenss time was even more varied, too multifarious, mutable and extraordinary to be confined within such an anthology as this. This does not attempt to be a social history of three-quarters of a century, but rather to provide in Jerrolds spirit a collection of illuminating and entertaining accounts of the changing life of the times, as observed and interpreted by a wide range of Dickenss contemporaries and by The Inimitable, himself one of the major social commentators and critics of the century.

As such, it includes writings from earlier in the century, before Victorias accession to the throne in 1837 (the year of Pickwick Papers), a period that not only shaped Dickenss imagination but provided the foundations for the developments of mid-Victorian England. It also includes some writing from the time after his death in 1870 that deals with the world that he had known; the England of the last quarter of the century was however, as is generally recognised, increasingly unlike early and middle Victorian England, with which this book is mostly concerned.

The subjects touched on include rich and poor, men and women, faith and doubt, entertainment and education, life in the country and in the town, and responses to that strange, un-English world overseas (as Browning wrote, What do they know of England who only England know?). Excerpts are drawn from popular novels and Parliamentary reports, from serious journalistic surveys to religious disputes and accounts of sports; poems, hymns and music-hall songs reflect the imaginative and emotional responses of the people generally. Each section also has a contextual introduction derived from modern research.

The period was one of change not only in society but in language usage; conventions of spelling, punctuation and grammar changed during the century, as they have since; to avoid unnecessary distraction, spelling and punctuation have usually been modernised (except where this would detract from the effect). Obscure words and phrases have been glossed in the body of the text, in square brackets; these are usually in the writing aimed at a more popular market.

It is worth remarking that at least a quarter of all books published then were religious and devotional works not adequately represented here. The middle classes patronised circulating libraries and authors less demanding and unsettling than George Eliot or Meredith the silver fork novel of refined manners was popular; despite Bozmania, Dickens was not altogether respectable. The working classes generally read little, though slowly improving education increased literacy: cheap periodicals and the cheap and coarse penny novel appearing in weekly parts (as a contemporary reported) did well and Dickenss own more mainstream Household Words and serial novel publication are well known.

The better nineteenth-century writing generally is vigorous, rich and inventive, less concerned with balance and rhythm as was the eighteenth century than with development of vocabulary and imagery. A wide variety of styles is represented here, with writers displaying notable idiosyncracies of expression; while Biblical echoes are frequent, some writers certainly were particularly responsive to urban speech habits, providing striking phrases and lively rhythms. Powerful emotionality, moral engagement, satire and broad humour and, especially, strong responsiveness to the material world abound. Particularly noticeable is a copiousness of language, an accumulation of clauses and adjectives; there is a remarkable particularity and thinginess in much Victorian art, whether in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites or in Gerard Manley Hopkinss Pied Beauty:

Landscape plotted and pieced fold, fallow and plough;

And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim

or in the catalogues tumbling through descriptions by George Augustus Sala and Charles Dickens, that do so much to bring before us the living and physical detail of the material and social life of the times.

Again and again, through acute observation, vivid detail and imaginative insight, these writers, from the famous to the obscure, give us the feel of what it was like to live in the exuberant, troubling and frequently horrible seventy-odd years of this age, times ostensibly very different from but, underneath, often remarkably like our own.

Comparisons with the past are absolutely necessary to the true comprehension of all that exists today; without them, we cannot penetrate to the heart of things.

Charles Booth, Life and Labour of the People of London (1889)

ONE

England and the English

D ickens grew up in the turbulent reigns of George IV and William IV, the years of the French wars, of the Peterloo Massacre, Captain Swing riots, the Romantic poets. When he died in 1870, England had been transformed: great smoky cities and factories, steam-engines, Gothic churches and neo-medievalism; the dumpy Widow of Windsor, soon to be proclaimed Empress of India (1876), ruled an empire so extensive that on it the sun had yet to set; the country was the richest in the world.

Nineteenth-century England experienced change social, economic, political and cultural to an extent and at a pace never previously known. The population increased rapidly, even overwhelmingly, from a little over 8 million in 1801 to nearly 23 million in 1871; people moved from the country to the towns, and the towns grew: at the beginning of the century, perhaps 20 per cent lived in towns of more than 5,000 people, in 1851, more than half did. Quite apart from London, the great Wen, the new industrial conurbations of the north and Midlands grew particularly quickly, with great mills, sprawling slums (so profitable for the landowners) and impressive public buildings. The industrial inventions of the late eighteenth century now bore fruit in the spectacular increase in the production of coal, iron, steel and textiles especially cotton. Over the century, coal production increased by twenty times, pig-iron by thirty, and total industrial production quadrupled.