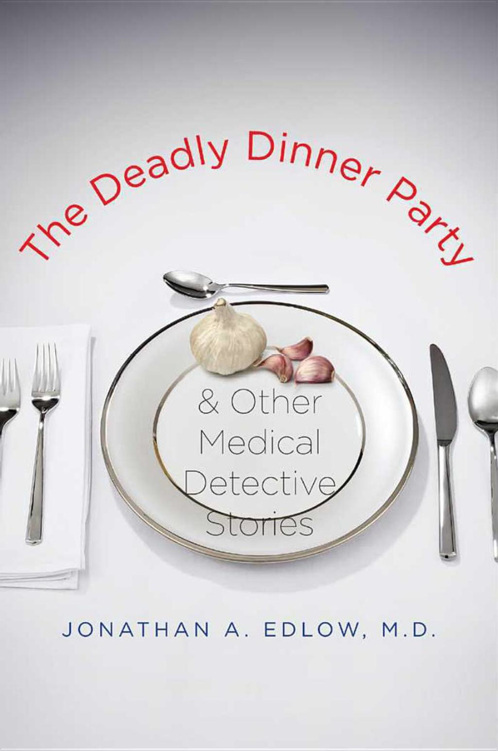

The Deadly Dinner Party

This page intentionally left blank

The Deadly

Dinner

Party &

Other

Medical

Detective

Stories

Jonathan A. Edlow, M.D.

y a l e u n i v e r s i t y p r e s s

n e w h a v e n & l o n d o n

Published with assistance from the Louis Stern Memorial Fund

Copyright 2009 by Jonathan Edlow, M.D. All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Janson Oldstyle type by

The Composing Room of Michigan, Inc. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Edlow, Jonathan A.

The deadly dinner party : and other medical detective stories /

Jonathan A. Edlow.

p.

cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-12558-0 (alk. paper)

1. MedicineCase studies. I. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Diagnosis, DifferentialCase Reports. 2. Disease

etiologyCase Reports. 3. Epidemiologic MethodsCase Reports.

4. InfectiondiagnosisCase Reports. 5. Poisoningdiagnosis

Case Reports. WB 141 E23d 2009]

RC66.E35 2009

616.075dc22

2009010830

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I have been blessed to find the love of my life, Pamela.

She encourages my writing because she knows I love it.

She edits my work to make it less obtuse. She supports me

when there is a deadlinewhich is most of the time! But

most of all, she makes waking up each day exciting and

gives me peace and hope.

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

This page intentionally left blank

When I was a teenager, my mother gave me a paperback book called TheMedical Detectives, by Berton Rouech. These stories had all been previously published in an occasional series in the New Yorker called the Annals of Medicine. I had never heard of the New Yorker back then, and I had no particular desire to pursue a career in medicine. But I do remember devouring these stories one after another, and being sad when each one was over and sadder still when I had finished the book.

The volume was a collection of real-life medical mysteriesclusters of patients with odd symptoms, bizarre outbreaks of unusual diseases, and full-scale epidemics. The common thread was diagnosis, but not just any diagnosis. In each case, the solution proved tough to find. It was never a simple x-ray or routine blood test that made the final diagnosis, but doctors playing detective. Some physician or medical epidemiologist had to delve beneath the surface to find all the pieces and solve the puzzle. The first of these stories that I ever read was called Eleven Blue Men. As it turns out, I was not the only person who found this story fascinating; the television series House used it for its pilot episode.

Another book that I read as a teenager was the Complete Stories ofSherlock Holmes. These yarns had the same effect on me, always making me wonder which facts would turn out to be clues and which were red herrings. I liked these stories and short novels so much that I reread the entire Sherlock Holmes canon as a college student.

Part of the appeal in both sets of stories was their lengthnot too short and not too long. As an adult, my attention span is not much longer than it was when I was a teenager, and I liked being able to read these tales in a single sitting. The second element they had in common was the simple pull of any detective story: figuring out whodunit and following, at least in retrospect, how the hero, whether an epidemiologist or Sherlock Holmes himself, solved the puzzle. Last, each of these miniature mysteries had all the elements of any good storyplot, char-ix

acter, and setting. The writing placed the reader in the midst of the investigation, just like Dr. Watson, the sidekick to Holmes.

Part of every doctors and epidemiologists job is to solve mysteries.

Many are not so challenging. A patient consults a doctor because of fever and bloody diarrhea after eating undercooked hamburger. The doctor sends a stool culture and E. coli grows out. Case closed. Or a patient shovels heavy wet snow, develops chest pains, and comes to an emergency department. An electrocardiogram shows a heart attack. Another patient seeks medical advice in June for a low-grade fever and a large, unusual red rash over the abdomen at the site of a tick bite. It doesnt take a Sherlock Holmes to diagnose Lyme disease.

But sometimes, patients present problems that can be far more challenging. The clues lead to dead ends. The x-rays, blood tests, and CT

scans are normal. Even smart doctors are unable to make a diagnosis. Or sometimes, they make a presumptive diagnosis, but the treatment fails.

In these cases, the doctor becomes detective and the diagnosis can be as elusive as any criminal. Clues may not be so easy to find, sometimes because they are hiding out in the open, just as in Edgar Allan Poes The Purloined Letter. Sometimes doctors may call in the local public health epidemiologists to help with the problem. In other situations, if the scope of the outbreak overwhelms local resources, the Epidemiology Intelligence Service of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will be called in. Dr. Alexander Langmuir created this service in about 1950 when he began training a cadre of young physicians to become the countrys medical sleuths.

The young men and women who work for this program today are

available on a moments notice, suitcases prepacked, to respond to any outbreak of disease or epidemic in the United States. They are famous for what Langmuir called shoe-leather epidemiology. They solve cases the old-fashioned way, like the detectives in any good mystery story

by knocking on doors, interrogating witnesses, coming up with hypotheses, and then testing them.

With this in mind, as an adult I began collecting my own medical mysteries and was fortunate enough to have Boston magazine and Ladies

Home Journal publish some of them. I thank all the many individuals who made time to share parts of these stories with me.

x

p r e f a c e

People necessarily have an anthropocentric view of the world, but even though we may be at the top of the food chain, that doesnt mean we have dominion over the world or our environment. As Friedrich Nietzsche put it, The human is by no means the crown of creation; every living kind stands beside it on the same level of perfection. In fact, we share our planet with an uncountable number of other species, each one scratching out its own ecological niche.

When humans fall ill to some virus or bacterium, it is simply the interplay between competitors in the same environment, each procreat-ing and fulfilling its own biological destiny. Several of the stories here may be classified as human meets pathogen. In The Deadly Dinner Party, a notorious bug makes its mark and turns a suburban meal into a disaster that almost claims its host. This case shows how a microorganism can strike, not through a direct assault on human beings, but by a toxin that it elaborates. A tale like this provides an extraordinary lesson about the history of the relationship between humans and our cohabi-tants on the planet.

Next page