The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

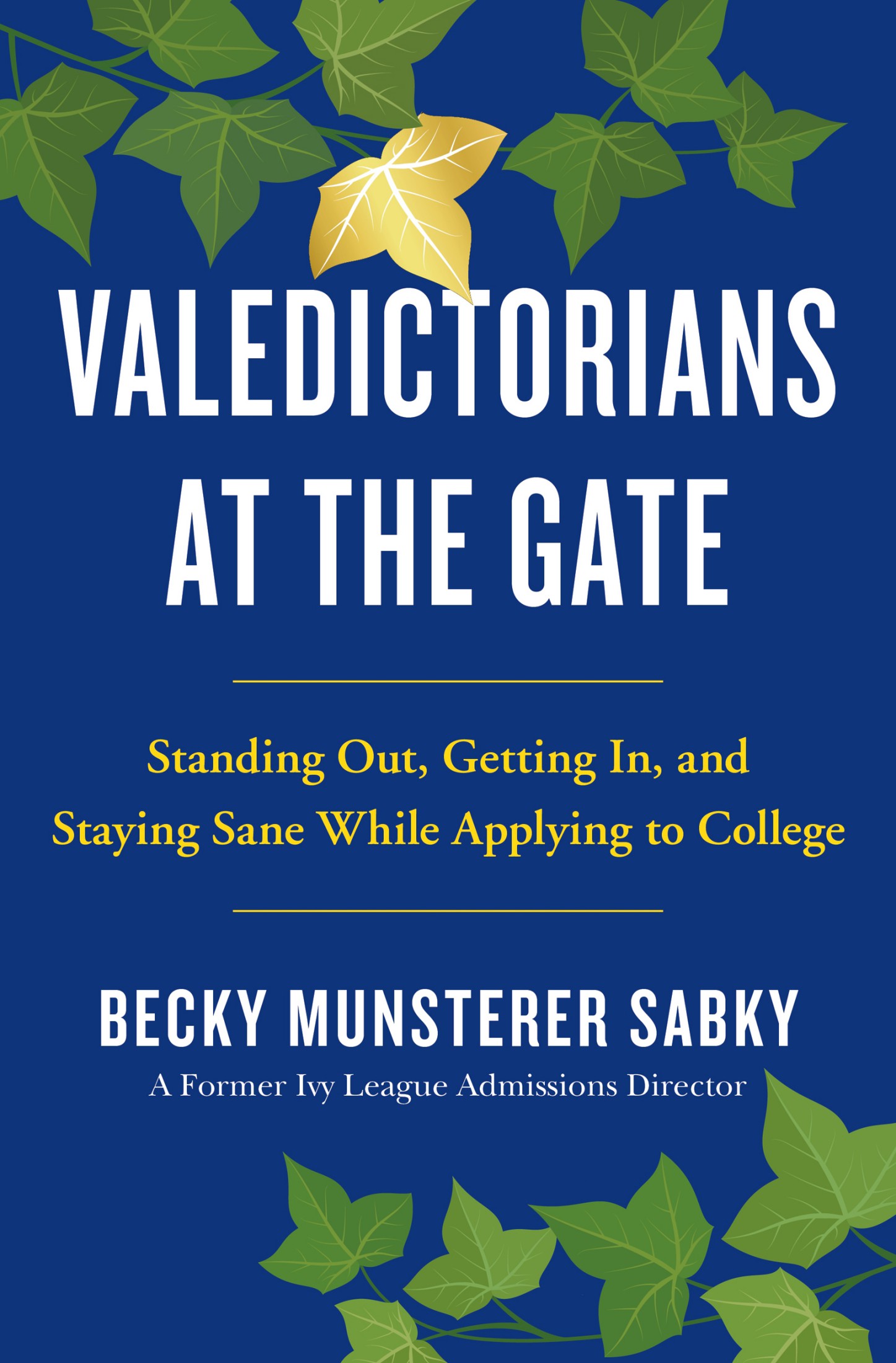

In 1997, I was denied admission to Dartmouth College. It was my first-choice school. I received the bad news from a dean of admissions I would curse for a week.

The denial was senseless. I belonged at Dartmouth. I was near the top of my class, was president of the National Honor Society, and had competed in the Junior Olympics for alpine skiing. My teeth were straight, my vocabulary was decent, and I wore conservative L.L.Bean sweaters designed for New England preps.

But something was wrong with me. Something wasnt good enough. I wasnt Dartmouth material.

I wasnt admitted to my second-, third-, or fourth-choice school either. (I spent the majority of April crying at the mailbox.) For someone who hadnt failed at much in my life, the rejections stung. I buried my Middlebury, Williams, and Bowdoin T-shirts far in the back of my closet, hoping Id forget the schools that broke my heart.

Colby College was my fifth-choice school. It didnt have the Ivy stamp. It wasnt as highly ranked as Williams. But as Id quickly learn, it did have an amazing creative writing department, a Rolodex of alumni happy to offer student summer internships, and perfectly crunchy onion rings. At Colby, I learned about Chaucer, microeconomics, and friendship. I used my creative writing skills to pen a few publishable newspaper columns (and to name dorm parties). I spent four years working hard as a student intern for the admissions office, which galvanized my love for all things recruitment. And life went on.

A few years later, a new application sat with the Dartmouth Admissions Office. After completing a two-year masters in the liberal studies program at Dartmouth, I decided to apply to work for the dean who had rejected me. I had two years of admissions experience at St. Lawrence University (a private liberal arts college in upstate New York), a graduate diploma, and a new set of L.L.Bean sweaters. Yet, after my first rejection, I wasnt sure Id land the job, nor was I sure I should have even bothered with another application.

Im glad I bothered. The same dean who denied my college application hired me to admit other college students. Id be a senior assistant director of admissions with my own office, my own travel territory, and my own Dartmouth business card. I was handed the magic wand and tasked with recruiting, reviewing, and admitting a class of students from the many applicants. This Dartmouth College reject would now do the rejecting. The irony was palpable.

I loved working in the office. But it was only after I worked behind the scenes that I realized how misguided my original notion of college worthiness was. As a trained, experienced, and decisive admissions reviewer, I was voting on a students application, not his person. My colleagues and I werent qualified to make statements of value or character. While we could open the gate for around 10 percent of the applicants to Dartmouth, it didnt mean they were more elite than others in the pool. We were simply creating a class to fill the colleges needs.

This book explores my personal experiences at the college over thirteen years as an Ivy League admissions officer. Its both narrative and prescriptive as I attempt to humanize the process and offer advice on how to survive the hullabaloo. Its filled with stories (both inspiring and head-scratching) and tips (e.g., the correct pronunciation of Worcestershire will wow a steak-loving alum during an interview). But most of all, its a guide to keeping perspective while navigating a complex process.

There are a few things to note before reading.

1.Ive changed identifying details to protect those involved.

Names, places, schools, and application specifics have been altered. Confidentiality is of highest concern to me, but Ive done my best to preserve the gist of my experiences. (So, if you believe youre the male chess champion from Connecticut who was denied from the college, I can assure you that the applicant was not male, did not play chess, and was not from Connecticut.)

2.I do not write about financial aid in this book.

I have never worked in financial aid. Im not trained in the process. Dartmouth had a need-blind policy for American citizens, meaning that admissions officers were not to consider ability to pay tuition as part of their decision-making process. While I was never exposed to the financial aid records of our applicants with United States citizenship and dont feel qualified to comment on financial aid practices, I cant emphasize enough my concern about college affordability and accessibility. Net price is critical to college access, and I believe financial aid to be of utmost consideration when applying to and choosing colleges. I encourage every applicant, regardless of family income, to carefully research and consider financial aid offerings and policies. (And I beg students to pick up the phone and call a colleges financial aid office if they have any doubts.)

3.Ive worked as an admissions officer at two institutions: St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, and Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. Ive admired (and still admire) them both.

St. Lawrence is my fathers alma mater. He loved his experience there, and his enthusiasm rubbed off on me at an early age. I dont write much about my time there because I spent two years in an entry-level position, learning the ropes of what it meant to be an admissions officer while also learning how to adult. (At SLU, I learned to never put a fork in a microwave, to always check the popcorn machine at the local bar for mice before taking a scoop, and to recruit tour guide volunteers with free pizza.) My time in the village of Canton, New York, confirmed my love for the profession (and my admiration for incredible colleagues), but most of my admissions career happened during my thirteen years at Dartmouth.

Dartmouth College is an incredible institution. It provided me with remarkable professional growth and outstanding travel opportunities. (On recruitment trips, I saw the Jungle Room in Graceland, the Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio, and the canals of Venice.) I still live a few miles from the Dartmouth Green and call many former colleagues friends. I have nothing but admiration for Dartmouths admissions office, its students, and its extended campus community.

But the obsession over getting into Dartmouth seemed all-consuming for many families. Most colleges admit the majority of students in their pools. Yet, in competitive college admissions markets, I witnessed many families who viewed admittance to top-ranked schools as a prize.

We need to help our students apply to college rather than compete for college. We need to remember that theres a school for everyone, and not everyone needs to attend any one school. We need to appreciate the path to the college gate, and not just celebrate the few who are passed through. And we must remind ourselves that admissions decisions arent value statements; theyre just business.

Twenty years later, Im grateful to Dartmouth for sending me the thin envelope. It made me a more sympathetic admissions officer. (I kept the letter in the top drawer of my desk in case I took myself too seriously in the position.) It taught me a lesson about valuing open windows rather than obsessing about shut doors. It made me recognize that a persons talents, work ethic, abilities, and character dont change whether they are admitted to their first-choice institution or not. And it inspired me to want to help others gain perspective on an admissions process gone mad.