Copyright 2007 Colin Gower Enterprises Ltd.

First Skyhorse Publishing edition, 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-4960-3

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-4961-0

Printed in China

Contents

SPECIAL FEATURE

SPECIAL FEATURE

SPECIAL FEATURE

CHAPTER ONE

Dr. Arthur Conan Ignatius Doyle: An Authors Life

Sure there are times when one cries with acidity

Where are the limits of human stupidity?

Here is a critic who says as a platitude

That I am guilty because in gratitude

Sherlock, the sleuth-hound, with motives ulterior,

Sneers at Poes Dupin as Very inferior.

Have you not learned, my esteemed communicator,

That the created is not the creator?

As the creator Ive praised to satiety

Poes Monsieur Dupin, his skill and variety,

And have admitted that in my detective work

I owe to my model a deal of selective work.

But is it not on the verge of inanity

To put down to me my creations crude vanity?

He, the created, would scoff and sneer,

Where I, the creator, would bow and revere.

So please grip this fact with your cerebral tentacle:

The doll and its maker are never identical.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, 1912

I t was the evening of Monday, November 26, 1894. The house lights were dimmed in Torontos Massey Hall and there was a palpable aura of excitement and high expectation as the speaker climbed to stand behind a high desk, drenched by a single point of light. He was certainly physically impressive, A giant in size. He looks to be about six feet four and is not at all slim reported the Toronto Star. The paper went on to be somewhat critical of the speakers declamatory style, and imply that if he had been lecturing on any other subject he would not have been so entertaining. Fortunately, however, the speakers subject was one that has been found continually fascinating for over 120 years, since A Study in Scarlet first appeared in Beetons Christmas Annual for 1887. The speaker was none other than Arthur Conan Doyle, and his subject was his own creation, possibly the most recognizable fictional character ever conceived, and the worlds first consulting detective: none other than the redoubtable Sherlock Holmes.

Conan Doyle lectured at Torontos Massey Hall.

Considering that the Toronto audience was full of Holmes aficionados, ready to hang on Conan Doyles every word concerning the great detective, the tenor of Doyles lecture was rather strange. He was at pains to convince his audience that, not only was Holmes no more, but that he would not be resurrected. According to the Toronto Star reporter, the author maintained that his personal literary interest was in writing bright pictures of chivalry and deeds of daring like those in which Scott won his fame. Conan Doyles literary canon does indeed contain many works of historical fiction, but these have substantially withered away from disregard. Conan Doyle continued his address by further distancing himself from his famous creation, whom he dismissed as his doll. The author also maintained that, far from having any ability to solve mysterious crimes himself, Holmes was actually far from being sharp, and had only the ability to put himself in the position of a shrewd man and imagine what the shrewd man would do.

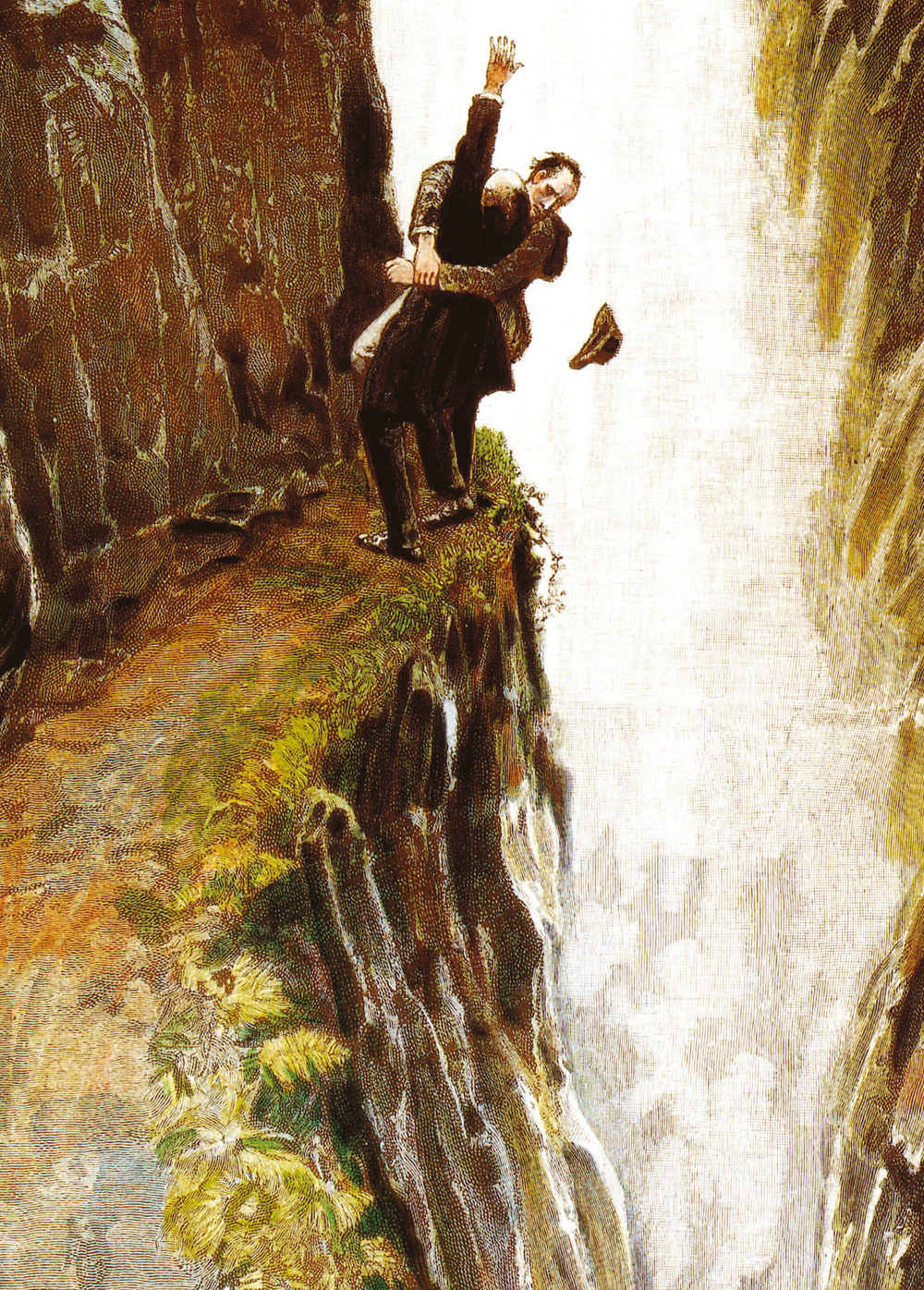

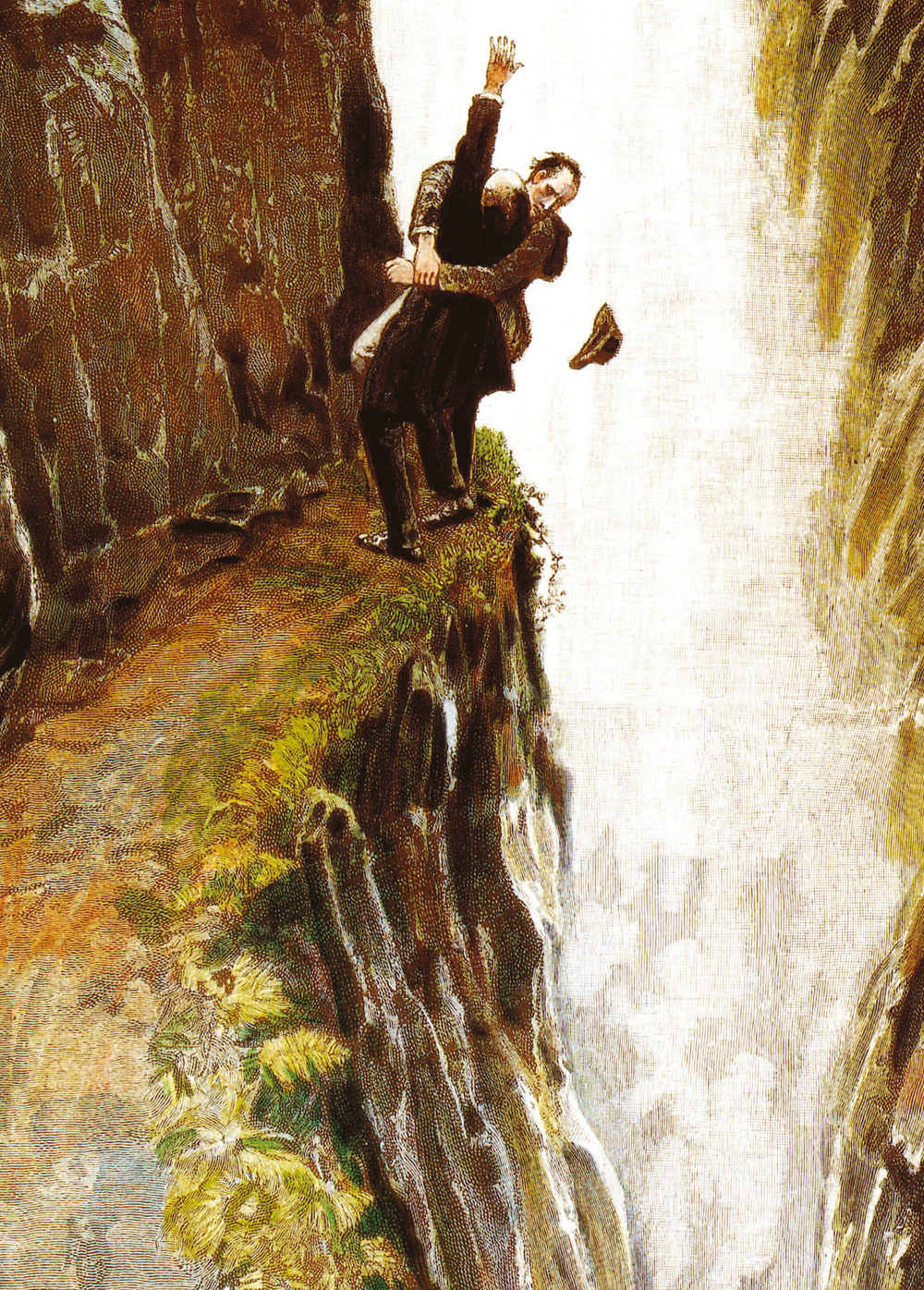

Conan Doyles most famous creation had actually already been sent to his demise. The Strand had published The Final Problem, the last story in the second series of Holmes stories, in December 1893, and for all his readers knew, the great man had fallen at Reichenbach never to return. (In novel form, these stories were published as The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes). A chance visit to the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland had presented Conan Doyle with an irresistible idea for Holmess demise, and he was quick to grasp it. He was already sick of writing about Holmes. The adventures of his famous detective tortured him with the constant need for plotting, devising, counter-plotting, and resolution. He wanted to exorcize himself of his wearisome creation, and had written to his mother I am in the middle of the last Holmes story, after which the gentleman vanishes never to return! I am weary of his name. He did this even in the full knowledge of the financial implications for him and his family, I must save my mind for better things even if it means I must bury my pocketbook with him. Conan Doyle planned to abandon the Holmes series as early as 1891, when he confessed, I have had such an overdose of [Holmes] that I feel towards him as I do toward pate de foie gras, of which I once ate too much, so that the name of it gives me a sickly feeling to this day. It seems that, at this point at least, author and character were in accord. As Holmes writes in a note discovered (after his cryptic disappearance) by his faithful associate Watson, my career had in any case reached its crisis, and no possible conclusion to it could be more congenial to me than this.

Next page