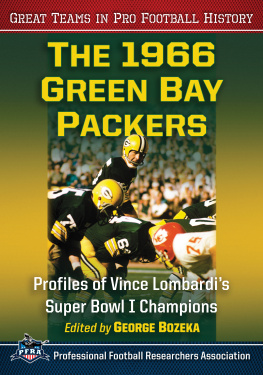

I want to thank the Green Bay Packer organization for the their assistance in researching this book.

Among the many sources consulted in this biography were the following books:

Barron, Bill, ed. The Official NFL Encyclopedia of Pro Football (New York: New American Library, 1982).

ESPN Sports Century, Bart Starr.

, Vince Lombardi.

Gruver, Edward. Nitschke (Lanham, MD: Taylor, 2002).

Kramer, Jerry. Distant Replay (New York: Jove, 1986).

. Instant Replay (New York: World Publishing, 1968).

. Jerry Kramers Farewell to Football (New York: Bantam, 1970).

, ed. Lombardi: Winning Is the Only Thing (New York: Pocket, 1971).

Lombardi, Vince. Run to Daylight (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963).

Maraniss, David. When Pride Still Mattered (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999).

Maule, Tex. Bart Starr: Professional Quarterback (New York: F. Watts, 1973).

Parcells, Bill. The Final Season (New York: Morrow, 2000).

Russell, Bill. Russell Rules (New York: Dutton, 2001).

Schoor, Gene. Bart Starr: A Biography (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977).

Starr, Bart. Starr: My Life in Football (New York: Morrow, 1987).

I T IS OFTEN said that, Nothing has happened since the sixties. Nothing. Virtually every social force leading into the new millennium has its genesis in the 1960s.

In electoral politics, the age of television and big money arrived in 1960 when John F. Kennedy used both to put away Richard Nixon in the closest presidential campaign in American history. With Kennedy, the heavy, staid air of the fifties began evaporating and was replaced with a vigorous, youthful optimism. In addition, the end of the aging and static Dwight Eisenhowers administration and the entrance of JFK signaled the beginning of the president-as-celebrity syndrome.

On the darker side, the specter of nuclear war developed realistic contours in that decade. The escalating Cold War, the arms race, and the Cuban missile crisis moved the thought of mass annihilation from science fiction into the daily newspapers, and into the mind of the American citizen. High school students gave speeches on the threats of Communism, the danger of nuclear testing, and the peril of stockpiling such weapons. Families, in preparation for a nuclear world war, built bomb shelters stocked with food in their basements. Today, the Cold War is over, but terrorism brings with it new, daily fears of mass destruction right in ones own country.

An atmosphere of continuous change, now a constant, has its roots in the sixties. (Ozzie and) Harriet Nelson and (Ward and) June Cleaver notwithstanding, the role of women was about to be altered radically. Many date the onset of that change to the publication of Betty Friedans The Feminine Mystique in 1963. Friedan recast the word woman, defining it in social and political rather than biological terms. The stage was set for mass education and professionalization of what once was culturally regarded as a domestic gender.

Civil rights also moved on to the main stage of the nation in the sixties. Martin Luther King, who mesmerized the nation with his I Have a Dream speech in 1963, led marches, sit-ins, and other nonviolent challenges to discrimination. An author, speaker, and one-man political force, the Nobel Prizewinning King became a political icon during the decade. Despite his commitment to peaceful social change, violence simmered under the surface. Other, more militant orators, H. Rap Brown, Stokeley Carmichael, and Eldredge Cleaver among them stirred the angry passions of the victims of racism. Cities burned, confrontations with the police became routine, and lives were lost, as blacks became more strident. King himself, the apostle of non-violence, was dead by an assassins bullet by 1968. He was just 39 years old. The era of the passive minority was over, and civil rights would never again be a back-shelf issue in American life.

Many historians also mark the sixties as the point at which America lost its innocence. Beginning with the unforgettable mid-day event in Dallas on November 22, 1963the assassination of President Kennedyviolence, disillusionment, and alienation became visible on the national stage. Before the end of the decade Malcolm X; Medgar Evers; Martin Luther King; and JFKs brother, Robert, would also be murdered.

Arts and leisure reflected the instability of the times. In pop music, the fifties crooners gave way to hard rockers, followed by a British invasion led by the Beatles and then a psychedelic era. The decade began with cigarettes and beer and ended with marijuana and LSD. Sexual mores changed as Hugh Hefner became a pop philosopher. Skirts went up and sexual prohibitions went down. By the end of the sixties, sex, drugs, and rock and roll became a lifestyle for many youths.

So also was protest. Throughout the decade an increasingly unpopular war in Southeast Asia was spilling the blood and draining the spirit of the country. Initially viewed as a heroic and necessary stand against the expansion of Communism, by the late sixties, the Vietnam conflict became regarded by many as a civil war in a nation thousands of miles away, one in which the United States should not be involved. So intense was the resistance to the war, that students burned draft cards, fled to Canada, and openly protested on the streets and university campuses. The word disorder became a major part of the American vocabulary and a seemingly omnipotent political figure, President Lyndon Baines Johnson, Kennedys successor, was all but driven out of office. Johnson, who in 1964 scored the greatest electoral triumph in American history, chose not to run for re-election four years later.

Even Americans favorite avenue of escape, the toy department of the culturesportswas not immune to high-speed shifts in the society. Sport changed forever in the sixties. Slow-moving baseball, long the only big-league sport, gave way to quick-breaking professional football as the sport of choice for many fans. It remains the preeminent spectator sport. Meanwhile, hockey and basketball were gaining momentum. College football and basketball reflected the changing politics of the sixties as black players became more prominent and vocal. The large halo-like Afro was more than a hairstyle. It was a political statement, as were the raised fists of John Carlos and Tommy Smith in the 1968 Olympics. Old, authoritarian coaches and baseball managers began to appear anachronistic and fell into disfavor, being replaced by younger, more democratic mentors.

Focus on the individual, though always a part of sportsparticularly baseball with its myriad statisticsreached its zenith in this decade. In 1961, Roger Maris, reluctant with his celebrity, hit 61 home runs, eclipsing Babe Ruths 34-year single-season standard of 60. Lew Alcindor (later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) was a proclaimed a near oneman gang in driving UCLA basketball to the pinnacle of college hoops. Roger Staubach and, later, O.J. Simpson became larger-than-life college gridiron heroes. Wilt Chamberlain, a veritable behemoth, demolished every meaningful record in the NBA. Brusque, foreboding Jim Brown began dominating NFL defenses. It was more than the feats of these athletic icons that characterized the decade; it was also the celebrity they enjoyed, as the new cultural giantthe mediabecame the force that enlarged them. The cult of the individual, however, extended beyond a focus on a players on-the-field exploits. From a self-aggrandizing standpoint, Joe Namathloud, arrogant, and hedonisticsymbolized the new athlete. Chamberlain also radiated a self-centered aura with his outspoken demeanor. Chamberlain, Namath, and others, however, were trumped by Louisvilles young and brash Cassius Clay, who changed his name to Muhammad Ali, refused induction into the military, and declared himself The Greatest, an unthinkable utterance in decades past. Were that not enough, sports reporting evolved into social commentary with the advent of Howard Cosellanother individual who became larger than the estimable contribution he made to sport.