The epigraphs preceding each chapter are selected from the beau tiful poetry of Saint John of the Cross, a sixteenth-century Spanish Carmelite friar whose writings on the spiritual life have been priceless for me. The quotations come from The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross, translated by Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez 1979, 1991, by Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites, ICS Publications, 2131 Lincoln Road, N.E., Washington, D.C. 20002, U.S.A. All of the quotations are from the 1991 edition. I am most grateful to the Institute of Carmelite Studies for permission to use this material. For more on John of the Cross, see my book The Dark Night of the Soul (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2004).

I also wish to thank my advance readers, especially my wife Betty, Jan Thurston, Betsy Moore, Gigi Ross, Gordon Forbes, and June Schulte for her detailed comments and for relaying her son Shilohs knowledge of bald eagle territorial defense.

FOREWORD

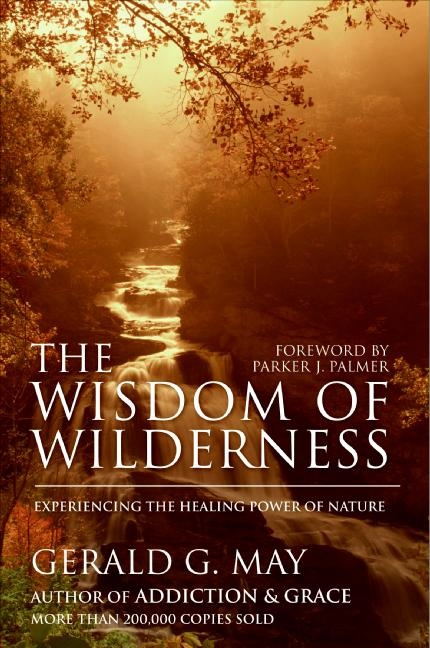

Jerry May knew he was dying as he wrote this book. So he gath ered up all the life he could hold with wordsas wild creatures gather food against a hard winterand left us a book so well stocked with love and wisdom, tears and laughter, healing and hope, it can help all of us winter through.

I met Jerry May in the early 1970s in Washington, D.C., where we worked together on several projects. We were young and unformed, but even then I knew I was in the presence of a good man, a brilliant mind, and a great soul. I was a community organizer, university professor, and spiritual neophyte. Jerry was launching out on three decades of profoundly life-giving work with the Shalem Institute, an ecumenical organization and community devoted to reclaiming the Christian contemplative tradition, enriched by insights from Eastern religions.

Signing on with the Shalem Institute was a turning point for this gifted psychiatrist who had served as a medic in Vietnam, a medic who refused to wear a sidearm and later became a conscientious objector. At Shalem, Jerry deepened his birthright gift for contemplation and began to interweave that gift with his psychiatric training. He found a platform for counseling, speaking, and writing from which he supported the spiritual growth of countless grateful people through personal contact and eight widely read, highly regarded books: The Open Way (1977), Simply Sane (1977), Pilgrimage Home (1979), Will and Spirit (1987), Addiction and Grace (1991), The Awakened Heart (1991), Care of Mind, Care of Spirit (1992), The Dark Night of the Soul (2005). At least two of his books (Will and Spirit and Addiction and Grace) have attained the status of contemporary classics.

When I met Jerry, he was just beginning to blaze a pioneering trail in the emerging field of contemplative psychology, which is credible and infl uential today in part because of his work. Without the grounding of psychology, contemplative insight easily becomes untethered, floating above the realities of our embodied lives. Without the transcendence of contemplation, psychology quickly diminishes us, reducing the human mystery to banalities like impulse and impulse management.

Early on, Jerry May became convinced that a contemplative psychology could embrace, in-the-round, the great conundrum of the Word-become-flesh that we call the human self. This, his last book, is rich with evidence that Jerry pursued this conviction until the day he died. In fact, I believe thatThe Wisdom of Wilderness opens new ground in the field Jerry helped to create precisely because of the end-of-life sensibilities he brought to writing it.

In one splendid passage, Jerry writes about his deep-woods encounter with a very large bear who came snuffling around his very thin tent in the middle of a very dark night:

I lie unmoving for a very long time after the bear leaves, my senses completely alert, no thoughts, no images, seeing nothing, hearing only my heart and breath and the sounds of the night. For the first time in my life, I am experiencing pure fear. I am completely present in it, in a place beyond all coping because there is nothing to do. I have never before experienced such clean, unadulterated purity of emotion. This fear is naked. It consists, in these slowly passing moments, of my heart pounding, my breath rushing yet fully silent, my body ready for anything, my mind absolutely empty, open, waiting. I am fear. It is beautiful.

For Jerry, contemplative psychology takes us beyond all cop ing to a place where we need not resist the difficult emotions of life but can become one with them, which helps us become one with ourselves. Looking back on his early psychiatric practice, he criticized himself for spending too much time helping people cope with their difficulties:

I have come to hate that word, because to cope with something you have to separate yourself from it. You make it your antagonist, yourenemy. Like management, coping is a taming word, sometimes even a warfare word. Wild, untamed emotions are full of life-spirit, vibrant with the energy of being. They dont have to be acted out, but neither do they need to be tamed. They are part of our inner wilderness; they can be just what they are. God save me from coping. God help me join, not separate. Help me be with and in, not apart from. Show me the way to savoring, not controlling. Dear God, hear my prayer: make me forever copeless.

Here, in a single vibrant paragraph, are a few of the gifts the reader will find in every chapter of this book: clarity and candor about the authors own journey; psychological insights turned upside down and made more piercing as a result; a turning toward prayer that is more in-your-face than pious; and all of it rendered in clear and compelling prose. What great gifts Jerry May brought to his work! What great gifts he left behind for us to cherish.

Intellectual power and spiritual courage were clearly two of Jerrys gifts; in the words of an ancient theologian, he knew how to think with the mind descended into the heart. But the impact of his workthe great and lasting legacy of hearts touched and lives transformed that Jerry left behindwould have been impossible, I think, had it not been for a third gift: Jerry possessed a sense of humor rooted in divine madness. As his family and friends will testify, he always saw the cosmic comedy in the human conditionyours, mine, and his own.