To my mother,

for sharing her sense of wonder with me

Contents

Guide

I NTRODUCTION

We are often described as sentient beings, but what does this mean? The word, from the Latin sentire, to feel, is so mercurial that the philosopher Daniel Dennett has, perhaps playfully, suggested, since there is no established meaning... we are free to adopt one of our own choosing. Some use sentience interchangeably with the word consciousness, a phenomenon that in itself is so elusive as to reduce the most stalwart scientific mind to incantations of magic. Marvelling at how brain tissue creates consciousness, how material makes immaterial, Charles Darwins staunch defender, T. H. Huxley, once pronounced it as unaccountable as the appearance of Djin [sic] when Aladdin rubbed his lamp; more recently, while probing the soft jelly of a patients brain, the neurosurgeon Henry Marsh agreed that the idea his fine sucker was passing through thoughts and feelings was simply too strange to understand. To some scientists, therefore, sentience becomes a hard if not the hardest problem in the study of the natural world. However, there is a simpler definition. Sentience also describes our ability to sense the world around us. Such sensitivity leads to our experiences of seeing the creamy white page of this book, feeling its weight in our hand, perceiving the murmur of a page turning, but sentience is then the foundation on which the mirage of consciousness shimmers. Scientists and philosophers debate whether animals experience consciousness, but most readily ascribe to them the pared-down version of sentience. This book reflects on how each of the sentient beings with whom we share the planet offers a different perspective on how we sense, even make sense, of the world and on what it means to be human.

The typical person, as Leonardo Da Vinci noted, looks without seeing, listens without hearing, touches without feeling, eats without tasting... [and] inhales without awareness of odour or fragrance. We are guilty of underappreciating and underestimating our sensory powers; after all, they circumscribe every waking moment. Observing how familiarity dulls our senses and anaesthetizes us to the wonder of existence, the biologist Richard Dawkins suggested that we can recapture that sense of having just tumbled out to life on a new world by looking at our own world in unfamiliar ways. Looking at our evolutionary family tree is one such way. We share a deep past with all creatures, but those I have chosen from sea, land and air epitomize one or more of the various senses. The spookfish has an uncanny ability to detect light in the oceans bathypelagic depths. The star-nosed mole navigates sunless subterranean tunnels through touch, whereas on moonless nights the male giant peacock moth finds females miles away through smell. An exploration of such excesses proves there is more to unite than divide us. Our furred, finned and feathered relatives offer insights across the range of human experience in all its shortfalls and surfeits. Through their eyes, ears, skins, tongues and noses, our familiar and ordinary become unfamiliar, extraordinary, and curious new senses emerge.

The sensorium that we parrot from nursery sight, smell, hearing, touch and taste was set out over two millennia ago in 350 BCE by Aristotle in De Anima (On the Soul). His concept of five senses persisted through Shakespeares five wits and, to this day, remains a near-universal belief expressed across cultures, not only in everyday conversation but also in scientific literature. However, modern science has proved Aristotle wrong. Today a human sixth sense once confined to the realms of pseudoscience with tales of telepathy or other extrasensory perceptions is not simply scientific fact but has been joined by a seventh, an eighth, a ninth and more. We still are in the grip of an Aristotelian view of our senses, said the philosopher Barry Smith, but if we ask neuroscientists, they say we have anywhere upwards of twenty-two. The neurobiologist Colin Blakemore confirmed this: Modern cognitive neuroscience is challenging this understanding, instead of five we might have to count up to thirty-three senses, served by dedicated receptors. Aristotles sensorium is proliferating.

Expert opinion differs on the final tally because there is, as yet, no consensus on how to define a sense. This shifts as scientists interrogate the substrate behind our various sensory systems. Some argue that it is folly even to try counting separate senses, as perception is about integrating information across them all, a fundamentally multisensory experience. We confuse the issue further in day-to-day conversation by invoking senses of loss and love, guilt or justice, art and music. While debate continues, what is not contested is that our eyes, ears, skin, tongue and nose support more than one way of seeing, hearing, touching, tasting and smelling and that Aristotle failed to identify a host of other senses that toiled tirelessly beneath his awareness. Science has since shown that our eye senses not simply space but time. Some suspect it may even sense location much like a navigational compass. Our inner ear hears, but also senses whether we are balanced and keeps us on an even keel. Our tongue smells and our nose tastes, as do other bits of our body. Our nose might also detect airborne messages that dont even have a smell. A strange variant of touch exists within our muscles that grants knowledge of where our body is, allowing us to move with coordination and without thinking; another might inform the profound sense of our self. Unaware of their workings, like Aristotle, many remain ignorant of these senses. Yet these and more alchemize into sentience. In his final article for the New York Times, written a few months before his death, the man once described as the poet laureate of neurology, Oliver Sacks, bade farewell: I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude... Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure. Open your eyes, ears, skin, tongues, noses and more to the everyday miracle of being sentient.

I

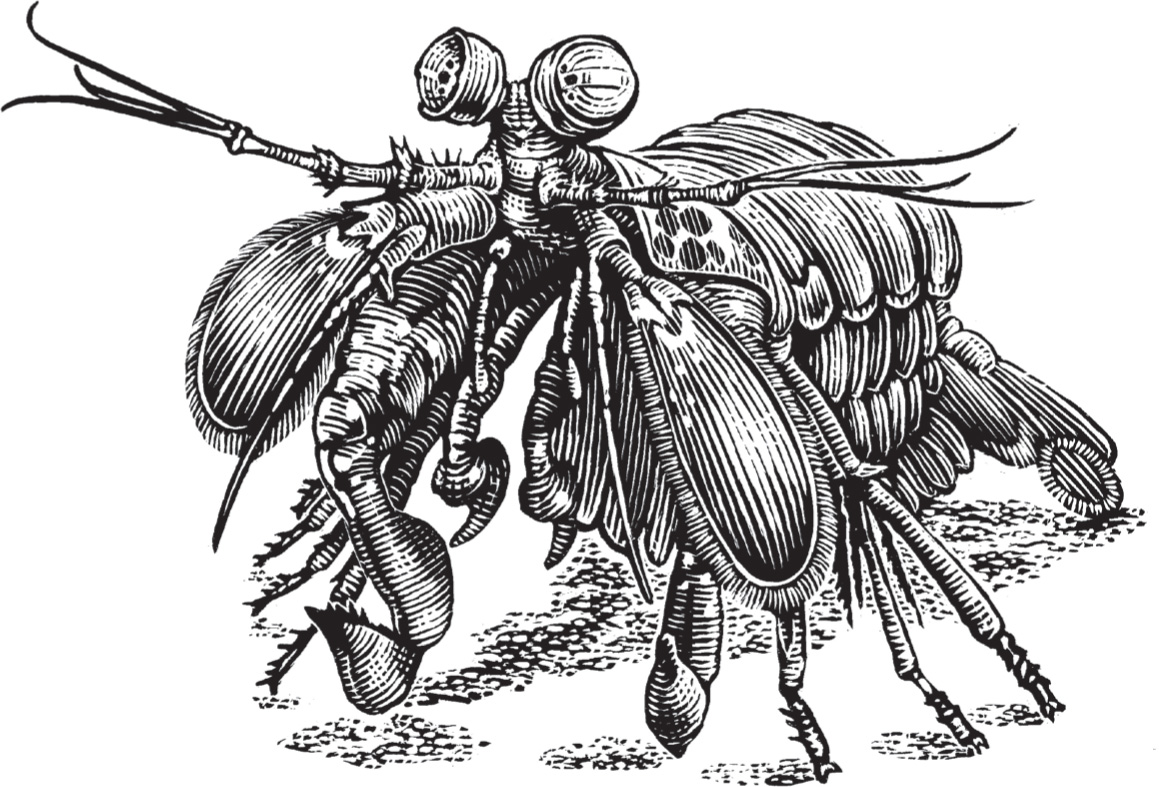

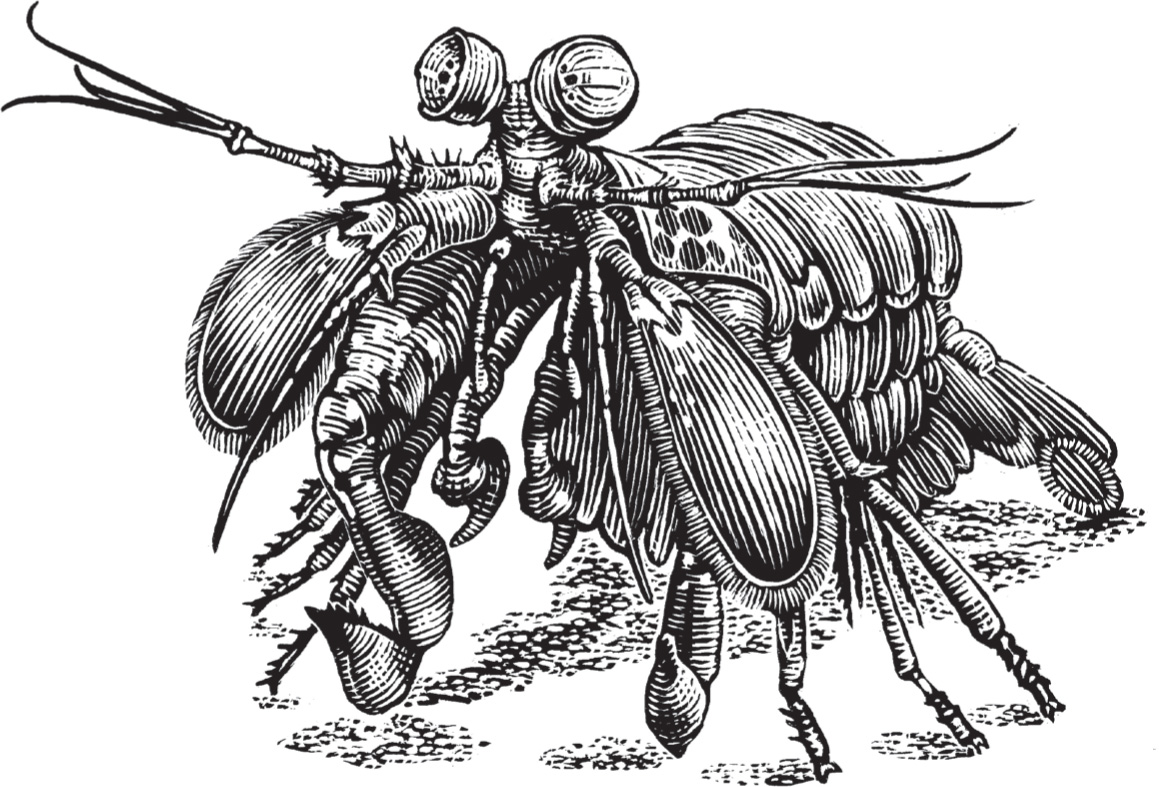

T HE P EACOCK M ANTIS S HRIMP AND O UR S ENSE OF C OLOUR

T rue to its various names, the peacock, painted or harlequin mantis shrimp is one of the most colourful creatures on the Great Barrier Reef. Neither shrimp nor mantis, Odontodactyllus scyllarus is more akin to a diminutive lobster with a kaleidoscopic carapace of indigos, electric blues and bottle greens. Yet this captivating countenance belies a somewhat irascible temperament. One spring day in 1998, at the Sea Life Centre in the English seaside town of Great Yarmouth, a particularly pugilistic specimen named Tyson astounded onlookers by smashing through the thick glass wall of his aquarium. He was clawing and snapping. Nobody dared touch him, the manager told the national press. All our visitors assume our sharks are the man-eating killers, but they are pussycats compared to Tyson. His power is incredible. Tyson was not the first to attempt such jailbreak; these marine crustaceans, known as stomatopods, have developed quite a reputation among aquarists and scientists. Indeed, research has shown that the peacock mantis shrimp uses its club-like arms to pack a punch faster and more forceful than any heavyweight boxer.