This is an impressive book. In writing it the author demonstrates great talent, as well as great courage.

No one that reads this book will be able to look at their family in the same way again.

An extraordinary family story Renato Cisneros delivers here the captivating narrative of a strange and disturbing filiation.

A loving and lucid puzzle.

People should read this novel to learn more about themselves.

Cisneros is a phenomenon in Latin America today.

A book so intelligent and moving, you wish it would never end. Libration (France)

The Distance Between Us is the story of a villain told from love. It dwells in the humanity hidden behind the themes left by war. It also narrates that other war: the one which all of us wage against our parents to become the persons we are.

The Distance Between Us goes far and appeals to the reader exactly because there is so little distance between what is written and what was lived.

Just as a father is never prepared to bury his son, a son is never prepared to dig up his father() It is within this tension that this magnificent novel lies, full of drama and suspense from the very first page.

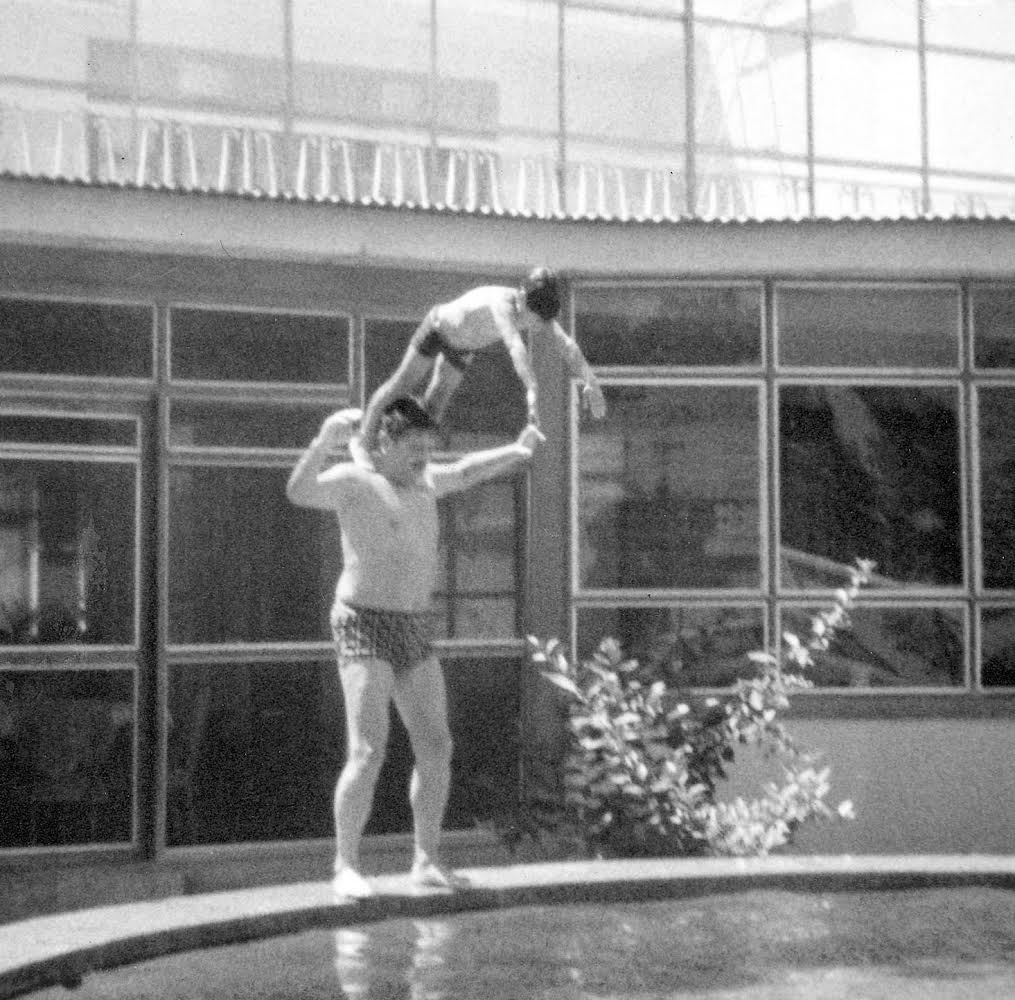

Renato Cisneros with his father (1980)

To my brothers and sisters,

who had a father named like mine.

The Distance Between Us

Chapter 1

I m not here to tell the story of the woman who had seven children with a priest. All Ill say for now is that her name was Nicolasa Cisneros and she was my great-great-grandmother. The priest she fell in love with, Gregorio Cartagena, was a high-ranking bishop in Hunuco, in the Peruvian Sierra, in the years before and after independence. Over the four decades of their relationship, both did what they could to avoid the repercussions of the scandal. Since Gregorio could not or would not acknowledge his offspring legally, he passed himself off as a distant relative, a friend of the family, so he could stay close to them and watch them grow up. Nicolasa reinforced the lie by filling out the baptism certificates with false information. This is how she came to invent a fictitious spouse, Roberto Benjamn, a ghost who played the role of legal husband and father. The day the children found out that Roberto had never existed and that Father Gregorio was their biological father, they resolved to break with their past, with their bastard origin, and made their second, maternal surname the only one, relegating Benjamn to a middle name.

Nor will I say anything here about the last of those illegitimate children, Luis Benjamn Cisneros, my great-grandfather. Nothing except the fact that his school friends nicknamed him The Poet. And that he was such a single-minded character that at the age of seventeen, he decided he was going to win the love of Carolina Colichn, the mistress of President Ramn Castilla. Whats more, he succeeded. By the time he was twenty-one they had three daughters together. The five of them lived hidden away in a squalid room in the middle of Lima, fearing retaliation. Early one morning, at the urging of his mother, who had just discovered the beleaguered life he was leading, Luis Benjamn left Peru and set sail for Paris, where he wrote romantic novels and guilt-ridden letters. Two decades later, he returned to Lima as a diplomat, married a young lady of fourteen, and became a father again, producing five further children. The next-to-last of these, Fernn, was my grandfather.

Fernn became a journalist and at the age of twenty-three was hired as an editor at La Prensa . After just two years he became the editor-in-chief, following the imprisonment of the entire editorial board under the dictatorship of Augusto Legua. He too suffered harassment from the regime and in 1921 was exiled to Panama, although he ultimately took up residence in Buenos Aires. By then, he already had five children with his wife, Hermelinda Diez Canseco, as well as a new-born baby with his mistress, Esperanza Vizquerra, my grandmother. Both women followed him to Argentina, where Fernn managed to support both families, while avoiding any contact between them.

But this novel isnt about him, either. Or perhaps it is, but thats not my intention. This novel is about my father, Lieutenant General Luis Federico Cisneros Vizquerra, El Gaucho Cisneros, third son of Fernn and Esperanza, born in Buenos Aires on 23 January 1926, died of prostate cancer in Lima on 25 July 1995. Its a novel about him or someone very like him, written by me or someone very like me. Its not a biographical novel. Not a historical novel. Not a documentary novel. Its a novel conscious of the fact that reality occurs only once and that any reproduction made of it is condemned to adulteration, to distortion, to simulacrum.

I have tried and failed several times to embark on this novel. Everything I wrote invariably ended up in the bin. I couldnt figure out the right texture for the copious material Id collected over the years. Its not that Ive clarified everything by now, but spitting out these first paragraphs anchors me, gives me purchase, provides an unexpected solidity. The doubts havent dissolved, but somewhere in the depths I can make out the glimmering granular light of a certainty. All I know for sure is that Im not going to write a novel about my fathers life, but rather about my fathers death: about what that death unleashed and revealed.

To do that, I have to go back to April 2006.

To what was going on in my life then.

Id been avoiding psychoanalysis for months. The end of my relationship with Pierina Arbul five years together, two years living together had devastated me. I was struggling to admit that my depression called for treatment. Id come and go from the newspaper office where I worked. Id come and go from my apartment. Id get up in the mornings, think, sleep. Especially sleep. And I was barely eating.

A friend put me in touch with Elas Colmenares, a psychoanalyst who received patients in a two-storey house on La Fuente Ave., near the corner of 28 de Julio St., in Miraflores. Since I lived just three blocks away, I agreed to try him out for purely geographical reasons. That was my excuse, at least. The day I saw him for the first time, Elas had just turned fifty. He had broad, rosy cheeks. His lively eyes, blue as mouthwash, stood out between his nose and the black line of his eyebrows. We entered a room, he closed the door, we sat down. Despite all his hyperactive tics, Colmenares conveyed an oceanic calm. His speech, varied and comfortable, resembled the room where he saw his patients: a portrait of Lacan, a yellow satin couch, puppets of Freud and Warhol and Dal suspended from the ceiling, a gladiolus in a pot, a cactus, copies of Picasso prints, a chessboard with two armies of wooden gargoyles lined up facing each other, a glass jar full of lollipops, miniature lamps, tourist guides to Athens, Prague, Rome, novels by Kundera and Garca Mrquez, LPs by Dylan and Van Morrison. Depending on the details that caught a patients attention, the room could have been the sanctuary of a restless adult or the refuge of an awkward adolescent. In our first two sessions, I was the only one to speak at all. Elas invited me to explain why Id come, and I felt a moral obligation to summarise my relationship with Pierina. I barely talked about anything else. I didnt mention my family or my tedious job. I briefly mentioned my fathers death, but I focused on Pierina: on how shed entered and exited my life, altering it, splitting it in two, like a bullet piercing a body and destroying its vital organs. From the leather sofa that served as his throne, Colmenares watched me, nodded, cleared his throat, completed the sentences I couldnt finish with teacherly aplomb. It wasnt until the third session that we had something resembling a real conversation. I was in the middle of a monologue about how horribly jealous Id become in my last months with Pierina, and I was blaming myself for having caused the break-up by harassing her, attempting to trail and control her. Id stopped acting like a boyfriend and become more like a police officer, I admitted, not looking at Colmenares, my gaze buried in the terracotta-coloured rug that covered the parquet floor. I was getting fed up with my own narrative, leading me as it did to reconstruct the fights that wore away at our relationship, the silences that hurt more than the insults, the insults that hurt more than the slammed doors, the slammed doors that recurred like bells tolling the hour. Suddenly, a silence fell that seemed to last an eternity. Colmenares broke it by changing the subject altogether.