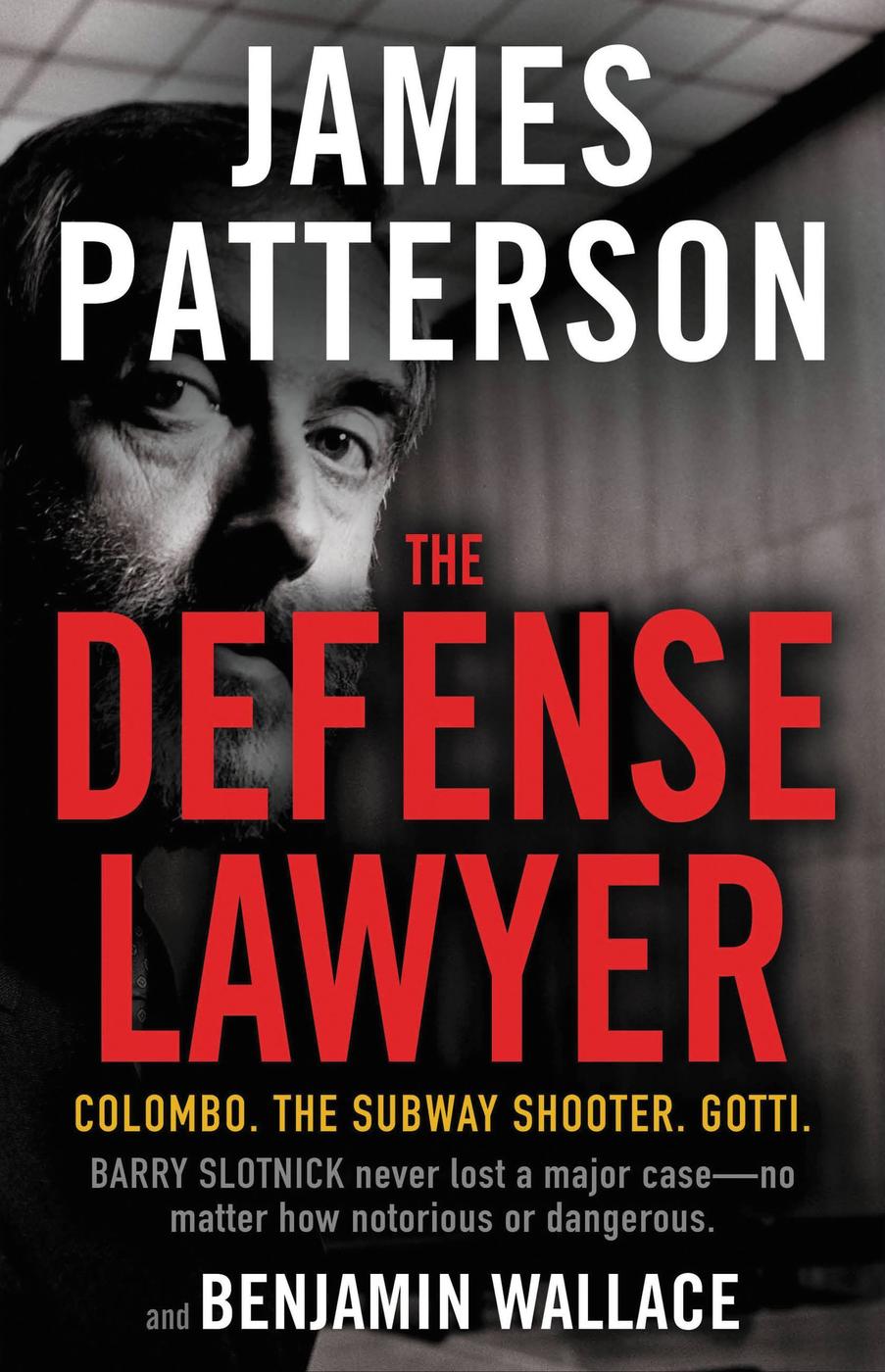

Copyright 2021 by James Patterson

Cover design by Mario J. Pulice

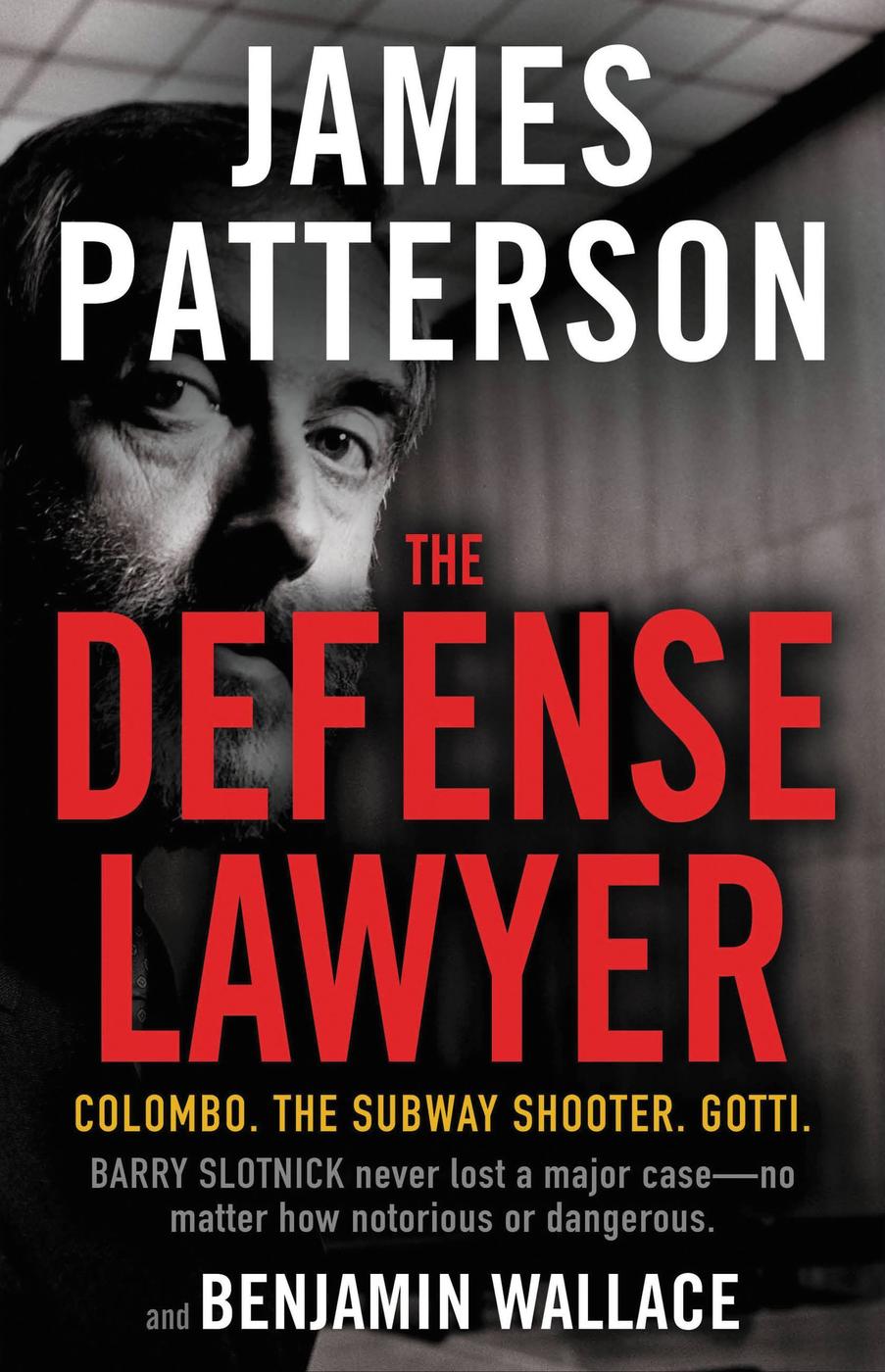

Cover photograph by Neil Selkirk

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

twitter.com/littlebrown

First edition: December 2021

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 9780316494380

LCCN 2020949148

E3-20211103-DA-PC-ORI

Whats coming next from James Patterson?

Get on the list to find out about coming titles, deals, contests, appearances, and more!

The official James Patterson newsletter.

I t was only around 4:30 p.m. on a Thursday, but Barry Slotnick had an early dinner to get to in the city before going home to Scarsdale, the affluent New York suburb where he lived with his family: his wife of nineteen years, Donna, and their four children. As Slotnick gathered his belongings, his eyes flitted over the framed illustrations on his walls, courtroom artists renderings of Slotnick arguing cases on behalf of a gallery of rogues.

His gaze kept returning to the windows. One of the reasons hed moved here to the Transportation Building was for the views. From his corner office on the twenty-first floor, Slotnick could take in a sweeping panorama that encompassed downtown Manhattan, the East River, and the Brooklyn Bridge. It never got old.

He said goodbye to his assistant, Pam, and stepped into the elevator. Moments later, he exited the building. Slotnick cut an impressive figure. He was six feet one and meticulously groomed, with a distinguished smattering of salt creeping into his neatly clipped beard. Despite the steamy July weather, he wore a tailored three-piece wool suit, a crisp white shirt, and a red power tie. The shirt cuffs, peeking out from the sleeves of his suit jacket, revealed a tastefully stitched monogram: BIS . It was a look befitting a man who was at that moment the most famous criminal-defense lawyer in America.

Slotnick stepped out on lower Broadway. He started to turn right, then glanced at his wedding ring, a trick he had come to rely on. Since childhood, hed had a form of dyslexia that made him hopeless at distinguishing left from right. By remembering that his wedding ring was on his left hand, he was able to navigate well enough. He turned in the opposite direction and began making his way across the street toward City Hall Park, a shaded plaza where his driver, Roberto, sat waiting to ferry his boss to his next appointment.

Slotnicks life was often stressful, but if there was ever a time when the forty-eight-year-old attorney might feel entitled to a rest, it was now, in the summer of 1987. Over the previous nine months, Slotnick had quarterbacked the successful defense in two of the most daunting and controversial trials in memory. First had come the prosecution of John Gotti, the dapper boss of the Gambino crime family, as part of an almost unprecedented legal onslaught against the Mafia by the federal government. Just a few weeks earlier, Slotnick had represented Bernhard Goetz, a white electronics engineer who had shot four Black kids he believed were about to mug him in a New York City subway car, in what was called the Trial of the Century (O. J. Simpson was still just a football star turned rental-car spokesman). But instead of resting after those two high-profile cases, Slotnick was busier than ever, carrying an alligator-skin briefcase in each hand. As he reached the car, a black Cadillac Fleetwood, Roberto popped the trunk from his seat behind the wheel, and Slotnick began putting the briefcases into it.

Just then, he felt a jolt, a searing sting in his back.

T he pain was sharp and sudden and had force behind it, like a knife thrust. Turning, Slotnick saw a man in a motorcycle helmet, its dark faceplate pulled down, swinging a blunt wooden object wrapped in newspapers toward his head.

Instinctively, he raised his left arm to deflect the blow. The weapon connected with his wrist, sending a shock of pain up his arm and a stab of fear through his whole body.

Although Slotnick was an urbane lawyer known for his twenty-five-hundred-dollar Fioravanti suits, he was not unacquainted with violence. Hed had a couple of close brushes with death many years earlierfirst when a bomb exploded at his office, and then when a client was gunned down while standing right next to him. But Slotnick had never been personally assaulteduntil right now.

He ran into the park to escape but had traveled only a few yards when the assailant caught up with him, raining blows on his back and arms with the weapon, which Slotnick thought might be a baseball bat with a nail sticking out of it. As bystanders approached, the assailant fledjumping on a waiting motorcycle piloted by a helmeted accompliceand sped away.

Slotnick stumbled back to the safety of his car, where Roberto apologized for not having been able to help. It had all happened so fast. Roberto had frozen and had only just managed to unfasten his seat belt.

I think my arm is broken, Slotnick said. Take me to the hospital.

As Roberto drove, Slotnick inventoried the damage. His left hand throbbed. There were puncture wounds to his right arm. His back and arms felt covered with cuts and bruises.

And he now noticed that his fifteen-thousand-dollar gold Piaget Polo watch had been lost in the scuffle.

At New York InfirmaryBeekman Downtown Hospital, an orthopedic surgeon X-rayed Slotnicks arm and found the fracture. Then Slotnicks nephew Rich, a Wall Street trader and martial arts black belt, arrived at the hospital, having heard about the attack on a newswire. Oh, Slotnick said. Karate boy shows up now.

Stuart Slotnick, a rising senior at Scarsdale High, was working the register at Sam Goody in the Galleria in White Plains when his friend Eddie called.

Eddie was so distraught he could barely speak. Your dad was attacked, he finally managed. I saw it on the news.

Stuart immediately called his mother. Everythings okay, Donna assured him. His wrist is broken, but hes okay.

At the record store, Stuarts manager came up to him and said, You should call home.

I know already, Stuart said.

Everyone at the job knew who Stuarts dad was.

M ore than a dozen newspapers from around the country were fanned out in front of Slotnick on his glass-topped desk the next morning. He was back in the office, and his assistant, Pam, had gotten them from a nearby newsstand that carried papers from around the country. Once she plunked them down in front of her boss, Slotnick awkwardly began flipping through the papers with his right hand. His left arm was immobilized in a sling.

Next page