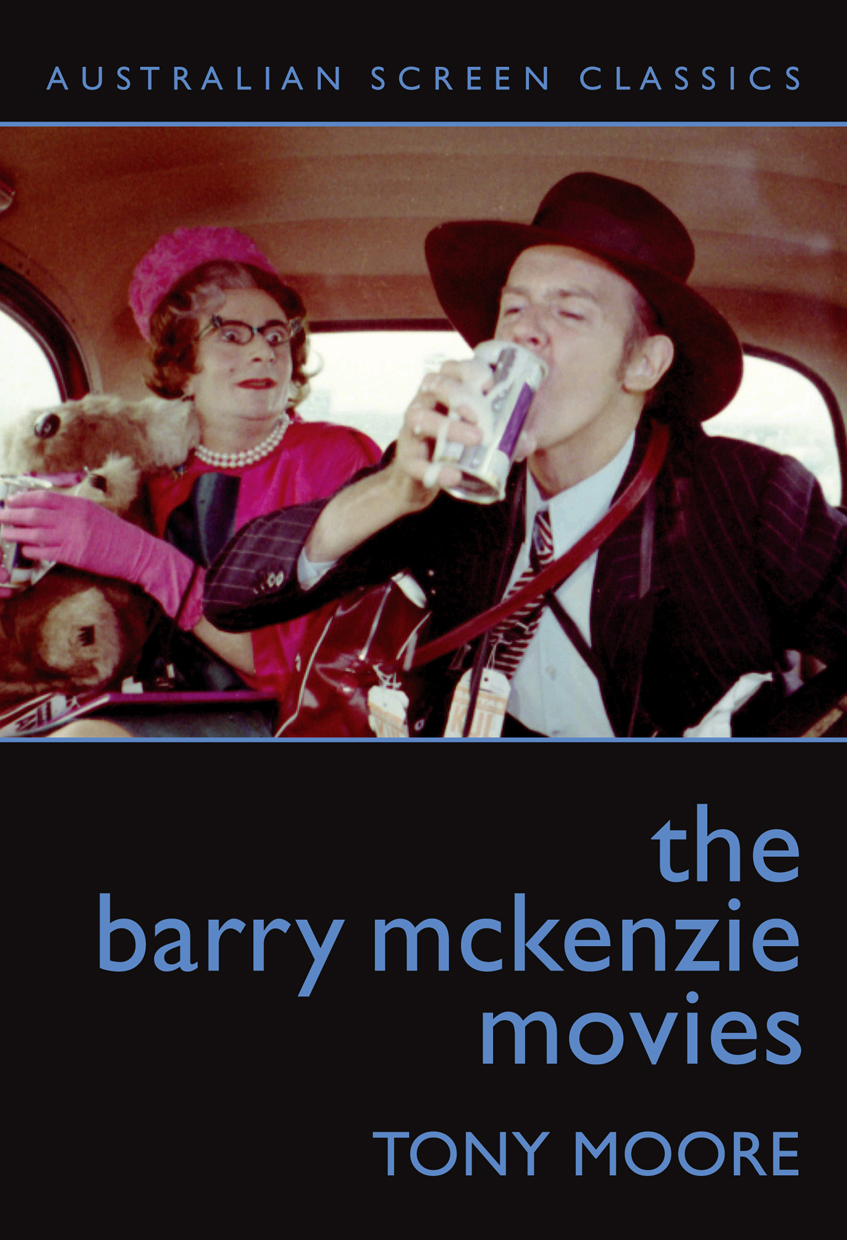

TONY MOORE

Tony Moore is a cultural historian, commentator and documentary filmmaker with a special interest in Australian pop culture, artistic bohemia and Labor politics. He is Commissioning Editor of Pluto Press Australia, prior to which he was a program maker at ABC TV where his last documentary was Bohemian Rhapsody: Rebels ofAustralian Culture, now the subject of a PhD he is completing at the University of Sydney. Tonys recent essay on Marcus Clarke, Urban Iconoclast, was selected for Best Essays 2005, edited by Robert Dessaix and published by Black Inc.

AUSTRALIAN SCREEN CLASSICS

Jane Mills

Series Editor

Our national cinema plays a vital role in our cultural heritage and in showing us at least something of what it is to be Australian. But the picture can get blurred by unruly forces such as competing artistic aims, inconstant personal tastes, political vagaries, constantly changing priorities in screen education and training, and technological innovations and market forces.

When these forces remain unconnected, the result can be an artistically impoverished cinema and audiences who are disinclined to seek out and derive pleasure from a diverse range of films, including Australian ones.

This series is a part of screen culture which is the glue needed to stick these forces together. Its the plankton in the moving image food chain that feeds the imagination of our film-makers and their audiences. Its what makes sense of the opinions, memories, responses, knowledge and exchange of ideas about film.

Above all, screen culture is informed by a love of cinema. And it has to be carefully nurtured if we are to understand and appreciate the aesthetic, moral, intellectual and sentient value of our national cinema.

Australian Screen Classics will match some of our best-loved films with some of our most distinguished writers and thinkers, drawn from the worlds of culture, criticism and politics. All we ask of our writers is that they feel passionate about the films they choose. Through these thoughtful, elegantly-written books, we hope that screen culture will work its sticky magic and introduce more audiences to Australian cinema.

Dr Jane Mills is a Senior Research Associate at the Australian Film, Television & Radio School, a member of the Board of Directors of Cinewest, and of the Sydney Film Festival Advisory Panel. She is currently writing a book about the relationship between global and local cinemas. Jane is a founder-member of Watch On Censorship.

acknowledgments

In writing this book I am indebted to small army of Bazza enthusiasts that include his creators, chroniclers and fans. I particularly want to thank Barry Humphries, Barry Crocker and Phillip Adams for their interest in this project and providing their reminiscences over the years.

A book like this rests on its research, and I gratefully acknowledge the people and institutions that helped me clarify my memories and correct my mistakes: Wendy Borchers at ABC TV archives; Morgan Gregory at the Australian Film Commission; TV historian Andrew Mercado; Kylie Connell at Grundy; Ian Duncan at The Whitlam Institute and the Honourable E.G. Whitlam who took it upon himself to check Hansard for a witty interjection no longer missing in action.

I salute those who fight the good fight to revive Australias lost film culture: the gang at Strewth! magazine for liberating Barry McKenzie Holds His Own from archive limbo; Alex Meskovic from the late, lamented Chauvel cinema for generously screening the classic; and Umbrella and their producer Mark Hartley for getting Holds His Own and all the extras onto DVDgo out and buy it! I want to express a special note of gratitude to Simon Drake and the team at the National Film and Sound Archive who co-publish Australian Screen Classics with Currency Press, and came up with a wealth of images for this book.

Books, like filmmaking, are a collective enterprise. Thanks to friends Chris Mikul and Ed Wright for kindly reading the draft manuscript and their sage suggestions, and to Richard White, my PhD supervisor at the University of Sydney, for disciplining my passions and flights of fancy with a respect for the facts. Thanks to Sam Clarke and Rob Kable for producing a promotional DVD for the book. I want to thank the creative team at Currency Press: Kate Florance for her wonderful designs; Claire Grady for proofing and typesetting and her patience with an author for whom dotting the i is not a natural inclination; Deborah Franco for publicity and Victoria Chance for having faith in me and Bazza. A special thanks must go the editor of this series, Jane Mills, for her guidance, patience, good humour, open mind and incredible knowledge. Jane has a vision for a living, critical cinema culture in this country, and for an ex-pom she certainly knows her Aussie movies.

Audiences are often the missing ingredient in film appreciation. This book is a belated cooee to my old schools mates (and odd teacher) at Port Kembla Primary and Kanahooka High where we honed the obsessive art of movie fandom.

Finally I want to thank my wife, Lizbeth, and children, Joseph and Eliza, for putting up with umpteen viewings of the Barry McKenzie films and for their infinite tolerance as I sat laughing at my laptop, singing chunder in the old Pacific Sea.

Tony Moore, 2005

For my parents,

Jean, Eric and Jim,

who taught me to laugh.

Introduction

Dinki-di Tales of a True-Blue Boy

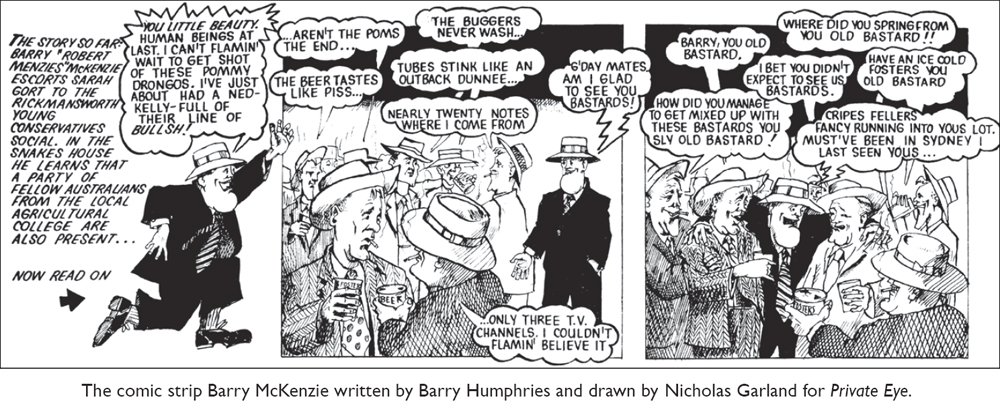

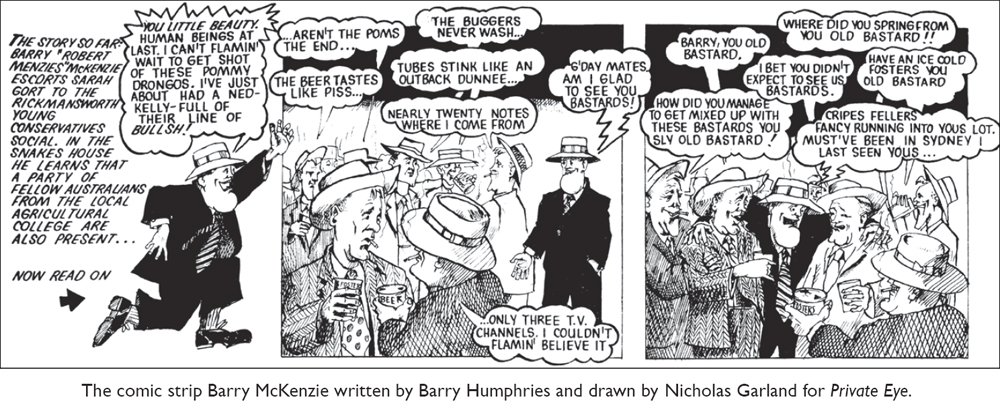

Struggling to make a living as an actor in pre-swinging 1960s London, a young Australian of bohemian habits accepted a commission to write a comic strip that was to change his life. His name was Barry Humphries and he had a gift for using humour to skewer his countrymens foibles. Peter Cook, editor of the satirical magazine Private Eye, asked the young expat to aim his barbed wit at the hordes of other young Australians then crowding into the west London neighbourhoods of Earls Court and Notting Hill, and Barry McKenzie, a young, uncouth innocent abroad, was born. Drawn by New Zealander Nicholas Garland, the cartoon Barry McKenzie looked like a cross between Chesty Bond and the Jolly Swagman, dressed in a 1950s double-breasted suit screwed down with a wide-brimmed Akubra hat that never left his head. Bazza, as he was known, was vulgar and irrepressible, perpetually sucking on ice cold tubes of Fosters, trying unsuccessfully to get a sheila into a game of sink the sausage, and chundering at will on unfortunate poms who crossed his inebriated path. He allowed Humphries to have a spray at everything he disliked about Australia and England. The strip became a cult hit in Britain. In Australia it was banned. Against the odds it was made into two early films of the 1970s Australian cinema revival, both directed by Bruce Beresford in close collaboration with Humphries.

Its difficult to believe that as a teenager I was allowed to show Barry McKenzie Holds His Own, the 1974 sequel to The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972), at my high school in 1976. Today, with lines like our dear little stunted, slant-eyed yellow friends and have a crack at putting the ferret through the furry hoop, it would ring alarm bells. But in the libertarian 70s our teachers knew nothing about political correctness. What we schoolboys knew was that this film, with its ribald humour, inventive Aussie slang, great songs, slapstick, beer, violence, vomiting, vampires, prostitutes and kung-fu fights, was a riot. And who could doubt that