For my family

Contents

Guide

In times of peace, the warlike man attacks himself.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Never easy, burpees. Never easy.

Joe Wicks

Prologue

Man Bites Pangolin

After fifteen minutes of remote learning, Ray, aged six, has already had enough. The video-conferencing app is malfunctioning, and the teachers voice is doing a weird echo thing reminiscent of an effect they used on dub reggae records in the eighties. OK, children. KRONG-KRONG-KRONG-krong-krong!! Is everyone muted? DOD-DOD-DOD-dod-dod!!

Im bored, Ray says. What can I doo-oo?

A few feet away, at the end of the kitchen table, I am wrenched away from the past-deadline TV treatment I am supposed to be writing, shocked by sudden stabs of despair and rage. A tiny still-calm part of my mind reflects on the surprising violence of what Im feeling and the strangeness that the simple act of supervising schoolwork from home should be quite so crazy-making. It considers the many places Id rather be: behind bars in the ad-seg wing of a large maximum-security prison; enduring a tongue-lashing from the demented guru of a cult in the Midwest; in Leeds huffing the cigar breath of a famous serial sexual predator.

Anywhere but here.

Eighteen months into the planetary pandemic, our three children have been sent home again because someone a teacher, a fellow pupil has tested positive. Nancy, my wife, is run ragged, verging on nervous collapse, on the rack of unrealistic work commitments, her own health not 100 per cent following a dalliance with the virus. Nieces, nephews, and two brothers-in-law are all ill, laid low by the Delta variant. And a few days ago word came that videos are travelling around TikTok, the sinister social media platform and data-harvesting tool, showing children how to hack their Covid tests with lemon juice so they can produce false positives and get themselves out of school. It turns out this latest bout of mayhem may all be down to some work-shy kids and a bottle of Jif Squeezy.

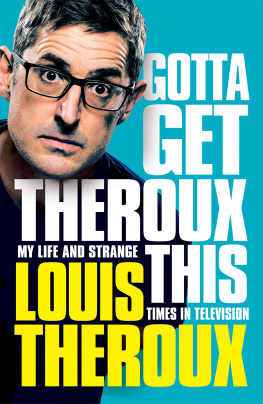

Like America, bombed at Pearl Harbor, the family Theroux finds itself dragged into a conflict it did not want, fighting on several fronts against the virus, against inconsistent and confusing measures intended to subdue the virus, against disinformation, against screen addiction, against an inability to agree on what we would all like to watch on TV.

A year and a half of madness has left its marks, even in the gilded world of a documentary presenter the Dame Vera Lynn of Lockdown Podcasting. Drinking too much, prone to embarrassing rages, losses of control and absent-mindedness, as well as feelings of inadequacy that may be the inevitable lot of a father trying to do his best, always on the verge of being cringe. Did I mention drinking too much?

I look back at the period of house arrest weve been forced into granted, with a few transatlantic work trips thrown in like a general surveying the ruined landscape of the territory hes conquered, pockmarked with the figurative scars of children going mental, squabbling and fighting, spending weeks on end without seeing friends, a beautiful and supportive wife grief-stricken at her lack of contact with the outside world, and the paterfamilias that being me who was confused and irresolute, and at times even weirdly appreciative of some aspects of the crisis, perhaps feeling that he needed to make his peace and get along with his new planetary roommate, the virus, since it wasnt showing signs of leaving, or maybe he was just too lacking in self-knowledge to know exactly what he was feeling half the time?

We may be near the end of this thing. We may not be. Ill say this for my friend Covid-19: it is full of surprises, and the good news is we have plenty of Greek letters on hand for its next David Bowie-like act of shape-shifting. Early in the whole adventure, in mid-March 2020, realizing we were entering an era of memorable weirdness, I began keeping a diary, which I continued for exactly a year. My decision to look back now may prove premature and hopelessly irrelevant, especially if a Sigma variant arrives that is more contagious and more debilitating, and is wearing platform heels with a red lightning bolt painted across its face. But if twenty-five years spent documenting the fringes of life and the most extreme forms of existential angst have taught me anything, its that often in the darkest times we find the most meaningful connection. So here I am, letting my readers in on a story that doesnt unfold in any of my usual journalistic feeding grounds of a porn set or a militia compound or a maximum-security psychiatric unit, but instead on a frontier much closer to home, one that has been the site of more stress and more fear for me, at least than any other Ive reported from, which is to say, my house, during a pandemic.

On the morning of New Yearss Eve 2019, I was pottering around in my kitchen in north-west London listening to the radio when a news item came on about a disease in Wuhan, China, linked to some kind of meat market called a wet market, a phrase Id never heard before that struck me as faintly grotesque. For a moment, I wondered why we were being told that someone 10,000 miles away had caught a virus, and why was it more important than all the other people who must be ill in China, in Darfur, or indeed on Willesden High Road. But presumably the editors of BBC Radio 4s Today programme knew their business it was news for a reason and my mind drifted, and I got on with other things.

It had been a busy holiday. We had taken over Christmas hosting duties from Nancys mum at late notice, because of a family illness. Nancy, on top of all organizing and coordinating of guests, was also in charge of the main meal. My job was the potatoes, which were, if I say so myself, a triumph par-boiled and shaken roughly in the pan to fluff them up, drizzled in olive oil, and then roasted into crispy golden perfection. I had ferried bottles of wine around for the guests Can I freshen you up? while swatting at my son Jack, who despite being twelve years old was attempting to cadge some for himself, ever curious to try anything with the cachet of the forbidden. Just a little sip, Dad, go on. After lunch with crackers and paper hats and the aforementioned magical potatoes, wed had a kickabout in the garden, then slumped in the front room and watched whatever was on TV. There was, naturally, a Christmas tree that our youngest son Ray had helped to decorate. We had put stockings out the night before, evoking the Yuletide magic in the appropriate fashion for a five-year-old. Dont forget carrots for the reindeer and some brandy for Santa... All three boys had put up stockings, even Arthur, who was fourteen and had made emphatic references to the mysterious workings of Saint Nick and his ability to defy physics and descend chimneys many times narrower than his girth, partly out of respect for Ray, but also mindful of not wanting his own Christmas privileges called into question.

Nancy and I had had our traditional argument over why I hadnt been more involved in getting gifts for the kids me thinking, though trying hard not to say, that if I could have taken some of their presents back to the shop, to decrease the number of their gifts, I would have been happy to. A thought partly born out of stinginess, but mainly out of a puritanical disapproval of excess and a sadness that ensued whenever I saw new possessions freed from their gift wrap only to grow old in a matter of hours, lose their magic, and become more clutter.