BRITISH KILLERS

Nine horrific true crime stories from the UK

and how they were solved

Volume 3

by GUY HADLEIGH

CONTENTS

JOIN MY VIP READERS GROUP AND GET 2 FREE BOOKS

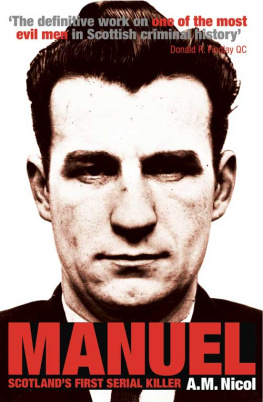

THE BEAST OF BIRKENSHAW

On Monday 17 September 1956, at her usual time of 8.45am, 57-year-old daily help Mrs. Helen Collison made her way around the side of 5 Fennsbank Avenue, High Burnside, Lanarkshire, Scotland, to the back door.

Number 5 was a small, neatly-kept bungalow owned by William and Marion Watt. William Watt, aged 52, was a master baker by trade and owned a large bakery in Glasgow. His wife had recently undergone a heart operation and was still not fully recovered. Mr Watt felt that he badly needed a holiday, so despite his wife's illness he had gone off on 9 September, alone except for his Labrador dog Queenie, on a fishing holiday to Argyll. His 16-year-old daughter Vivienne and Marion's sister, 42-year-old Margaret Brown, were looking after his wife in his absence.

Mrs. Collison had noticed that all the curtains were still drawn, and when she reached the back door she found it locked instead of being open, as it usually was at that time of day. She knocked twice, but received no reply. Then she made her way back round to the front of the bungalow, calling out to Mrs. Watt at each curtained window, but without success.

Nobody stirring

As she passed Vivienne's room, she saw that the window was slightly open. She prized it open a little more until a window lock stopped her from opening it further, but this was enough for her to be able to see inside. She could make out the shape of the bed, and what she thought was a figure at the foot of the bed. But still she could make no-one hear her.

Mrs. Collison then walked round to the front door, intending to ring the bell, but when she reached it she saw that the glass panel above the lock had been smashed. She looked through the hole and noticed that every door inside the bungalow was open, which was unusual. She shouted to Mrs. Watt again, without success.

Thinking that there might have been a burglary, Mrs. Collison went to one of the neighbors homes and told the woman what she had discovered. They both returned to No. 5 and tried knocking again. Then the postman joined them, out his hand through the broken pane of glass and slipped back the door catch. Mrs. Collison brushed past and made her way to the bedroom, where she thought she might find Mrs. Watt.

The sight that met her eyes made her cry out. In the curtained room were the bodies of Mrs. Watt and her sister in bed, and both pillows were soaked in blood.

Daughter dies

Bravely, Mrs. Collison went to young Vivienne's bedroom. Pushing open the door, she made another grim discovery. Vivienne was also lying in bed, her head on a bloodstained pillow. As Mrs. Collison approached, the girl gave out a spine-chilling groan and died before her eyes.

Police were at the scene within minutes. They soon established that all three victims had been shot by a .38-calibre revolver, and at point-blank range. There did not, however, seem to be any motive for the killings as there was no evidence of robbery or of sexual assault. But for some reason food had been scattered over the floor.

The pathologist confirmed that Vivienne had only recently died. He found a bruise on the left side of her chin and a bullet wound on the outer side of her left eye. Mrs. Watt had a bullet wound on the outer side of her right eye, and Mrs. Brown had wounds under her right eye and one on the side of her head. All the gunshot wounds were surrounded by powder burns, proving that the shots had been fired at close range.

The officer in charge, Superintendent Andrew McClure, also noted that Vivienne's body was in an unnatural position, with her right arm behind her back. Clothing found on the floor had been torn, and her wrist-watch had stopped at 2.52. There was a broken lamp base and pieces of light bulb and buttons on the floor, and also a button on the bed.

There had been two other break-ins in the area. One, the previous evening, had occurred just before midnight at 18 Fennsbank Avenue, a few houses away from the Watts's. Money and jewelry had been stolen, soup had been poured from tins on to the carpet and shoe marks left on the bedding. The other incident happened the night before that, on 15 September, at a house in nearby Bothwell. There too food had been scattered and footprints left at the scene.

Suspicion, both for the burglaries and the murders, immediately fell on a local man, Peter Thomas Anthony Manuel, who was well known to the police for theft and sexual offences. He had started out as a lone operator, but had recently teamed up with other local burglars.

Detective Chief Superintendent Hendry of the Lanarkshire CID was put in charge of the investigation. Within 24 hours of the grim discoveries he had arranged for a search warrant to be issued to gain access to Manuel's home in Birkenshaw, Oddington, and by 2am on 18 September police were banging on the door of the house where Manuel lived with his parents.

But Manuel refused to answer any of their questions. His clothes were inspected and the house searched, but no evidence was found, and the police were forced to leave empty-handed.

Police then turned their attention to another suspect, William Watt. He was staying in the Cairnbaan Hotel in Lochgilphead, about 85 miles outside Glasgow. Police broke the news of the murders to him there and arranged for him to be brought home.

The proprietress of the hotel, Mrs. Leitch, said William Watt had arrived on 9 September and that she had seen him at midnight on Sunday 16 September in the hotel. He had told her he wanted to go fishing before breakfast the next day, so she gave him the kitchen alarm clock. Watt had remained with Mrs. Leitch, her husband and another couple until about 12.30pm and he was seen again just after eight the following morning.

The police theorized that he could have driven home that night, committed the murders and arrived back at the hotel in time for breakfast: the journey time would be about two hours 15 minutes, and an experienced police driver took 11 minutes less than that to do the journey. But there had been a very heavy mist at Lochgilphead on the night of the murder, and this would have made the journey much longer.

Despite this apparent alibi, the police were still not happy with Watt's story, and when they heard there were rumors of him having had a mistress in the past they decided to pursue their enquiries. They found a ferry master and a motorist who had seen a man of Mr Watt's description on the Renfrew ferry on the night of the murder. This seemed to point to Watt once more: the ferry ride made an ideal short cut across the Clyde. Watt was put on an identity parade, and both witnesses picked him out as the man they had seen.

Husbands apparent calm

The matter was clinched in the minds of the police when the sergeant who had driven Watt part of the way home from the hotel reported to his seniors that the bereaved man had seemed anything but grief-stricken during the journey. Watt was arrested and charged with the three murders, and on 22 September was taken to Glasgow's Barlinnie Prison.

On 2 October Peter Manuel was sentenced to 18 months' imprisonment for the attempted burglary of a colliery office. He too was sent to Barlinnie, where he met up with Watt and goaded him that he knew the identity of the real killer of his wife, daughter and sister-in-law. On 8 October Manuel also wrote to Watt's solicitor, Laurence Dowdall, asking him to visit him in prison, as he had information 'of mutual advantage'. Intrigued, Dowdall went to see Manuel on 10 October. Manuel told him details of the crime that he said had been obtained from the killer.

Dowdall knew these details had not been published in any newspaper reports, and was convinced that the reason Manuel knew them was that he himself was the killer. When confronted, Manuel denied it but refused to reveal the name of the real killer.

Next page