For more than a century the term mafia has been synonymous with Italian organised crime. The word usually refers to the Sicilian La Cosa Nostra but is also commonly applied to the Neapolitan Camorra in the Naples and Campania region and the Calabrian ndrangheta (pronounced en-drangay-ta) in the far south of the country. Although less well known than either of its rivals, the ndrangheta is today considered by many international law enforcement officials to be more powerful, more dangerous and more wealthy than the other two. It is the ndrangheta that dominates Italian organised crime in Australia.

John Dickie, professor of Italian Studies at the University of London, and author of Blood Brotherhoods: The rise of the Italian mafias, observes that all three mafias have their foundation in myths of an ancient culture which heroically and nobly defended itself by forming an entity called the mafia. The truth, however, is different. According to Dickie, around the mid-nineteenth century bandits and prisoners in the jails of southern Italy began to organise themselves into secret societies with complex initiation rituals, strict rules and rigid hierarchies. These organisations began to run the jails from inside and to gain control of territories, exerting influence on authorities through bribery and threats of violence. Over time their economic power grew and they became a significant force in local politics.

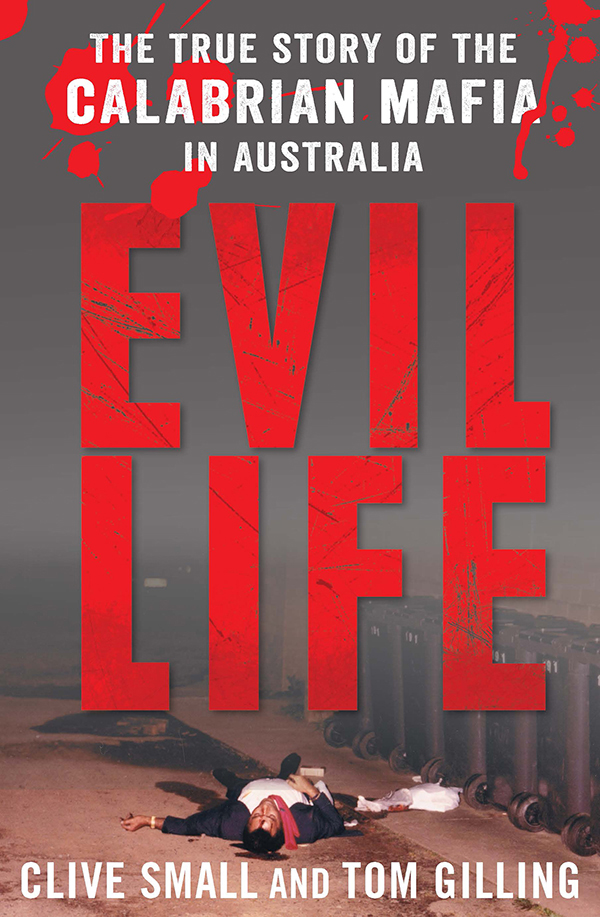

The mafias of Sicily and Naples emerged during the 1860s and the Calabrian mafia in the mid 1880s. Dickie notes that from the outset, one of the things that distinguished the mafiosi from other gangsters was their sense of history, mythical or not. It provided justification for their existence and their authority. In the early days the terms camorra and honoured society were used to describe all three mafias. Camorristi were slum-dwellers rather than middle-class hoodlums. The term mafia emerged in the 1860s. According to Dickie, in the dialect of Palermo the word denoted beauty and self-confidence. Picciotteria, meaning lads with attitude, was applied to the Calabrian mafia and to lower-ranking members of the Neapolitan Camorra. The term black hand was a catch-all label for Italian gangsterism in the United States and other countries and derived from the black hands, bloody daggers and so on that mafiosi sometimes drew on their extortion letters. The Calabrian mafia was often referred to as the evil life.

While the Neapolitan mafia has always been known as the Camorra, it was only in the mid 1950s that the Calabrian mafia became known as the ndrangheta (meaning manliness or courage). In the 1960s the name Cosa Nostra (our thing) became the standard term for the Sicilian mafia.

The Australian public remained largely unaware of the existence of the Calabrian mafia until the 1977 murder of Griffith resident Donald Bruce Mackay. The 43-year-old anti-drugs campaigner and Liberal Party activist was shot at least three times with a .22-calibre weapon in the car park of the Griffith Hotel.

As a result of the murder and the burgeoning drug trade the state Labor government set up the New South Wales Royal Commission into Drug Trafficking (197779), led by Justice Philip Woodward. The commission found that Mackay had been murdered by the ndrangheta to protect its multimillion-dollar cannabis cultivation and distribution operation. More than 30 years later, Mackays body has not been found. Those who ordered his assassination remain free: some still walk the streets of Griffith today.

Justice Woodward was not the first to warn Australian governments and law-enforcement agencies of the threat posed by the ndrangheta. More than a decade before Mackay was killed, the Victorian Government had come under intense political and media pressure after a string of murders and attempted murders of people connected with Melbournes Queen Victoria Market. (These became known as the Victoria Market murders.) The government had responded by enlisting John T. Cusack, a District Supervisor in the US Bureau of Narcotics and an expert in Italian organised crime, to help the Victoria Police Homicide Squad investigate the killings. Cusacks was the first major assessment of Italian organised crime in Australia.

Cusacks 1964 review was not limited to the Victoria Market murders or to Victoria; it also examined the history and activities of the Calabrian mafia in other states, particularly Queensland and New South Wales. Cusacks conclusions were blunt and unequivocal: The Calabrian LOnorata Societa [the Honoured Society] is well entrenched in Australia. It was engaged in extortion, prostitution, counterfeiting, sly grog, breaking and entering, illegal gambling and the smuggling of aliens and small arms. If unchecked, it was capable of diversification into all facets of organised crime and legitimate business To further their legitimate endeavours and cloak their illicit operations, Society members [will] conduct a well-planned program of ingratiating themselves with people of all walks of life. After making his report to the Victorian Government, Cusack was asked by the New South Wales Government to continue his study of the ndrangheta in that state. The conclusions he reached were similar.

Cusack was not the only foreign expert to be called in by the Victoria Police. Another was Dr Ugo Macera, an officer in the Italian police force. Asked for his assessment of the Italian crime problem, Macera concluded, like Cusack, that there was no doubt the [Victoria Market] murders originated from Mafia type criminal activity in Victoria. Unlike Cusack, Macera considered that the organisation was of a limited size, involving only a few unscrupulous individuals. (Macera noted, however, that his research was hurried.)

On being advised of Cusacks and Maceras findings, the Commonwealth Director-General of Security ordered an inquiry to gauge the extent, if any, to which secret organisations such as the Mafia have developed in Australia and to assess the future threat, if any, to Australia. The inquiry was to examine all available material from Commonwealth and State Police sources and relevant Commonwealth Departments. Colin Brown of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation was seconded to the Commonwealth Attorney-Generals Department and began his inquiry in 1964. The scope of Browns review was significantly greater and his report was the most detailed and comprehensive of the three.

Browns report has never been officially released, although it broadly follows Cusacks analysis, which refers to serious crimes that were widely reported at the time. Portions of the report have been published and his work has been cited in police records and reports, court records, newspapers, books and other documents dealing with crime and the growth of the ndrangheta in Australia.

In his report, The Italian Criminal Society in Australia, Brown agreed with Cusack rather than Macera. Like Cusack, Brown found that a Calabrian organisation known as LOnorata Societa or the ndrangheta existed in Australia and was involved in a range of serious criminal activities including murder, bombing, extortion, immigration rackets and corruption. The organisation, he said, had been successful in soliciting the support of members of various Australian parliaments, and was actively recruiting members living in Calabria to migrate to Australia.

The report claimed there was considerable evidence that there was a secret criminal organisation operating within Australia believed to be Calabrian rather than Sicilian or Neopolitan and loosely organised but rigidly controlled under the traditional system. It appeared to be autonomous within Australia and not controlled from Calabria, although it was dependent upon Calabria for its new recruits.