William Dalrymple

The Age of Kali

William Dalrymple is the author of seven acclaimed works of history and travel, including City of Djinns, which won the Young British Writer of the Year Award and the Thomas Cook Travel Book Award; the bestselling From the Holy Mountain; White Mughals, which won Britains most prestigious history prize, the Wolfson; and The Last Mughal, which won the Duff Cooper Prize for History and Biography. He divides his time between New Delhi and London, and is a contributor to The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, and The Guardian.

www.williamdalrymple.uk.com

By the same author

In Xanadu: A Quest

City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi

From the Holy Mountain:

A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, OCTOBER 2012

Copyright 1998 by William Dalrymple

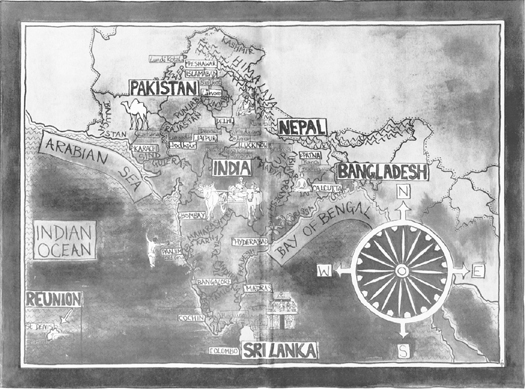

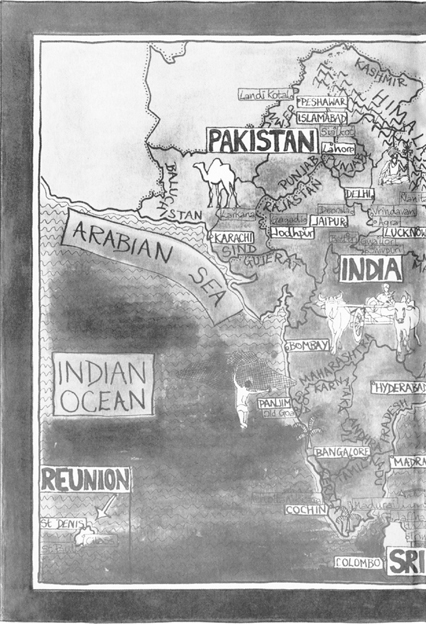

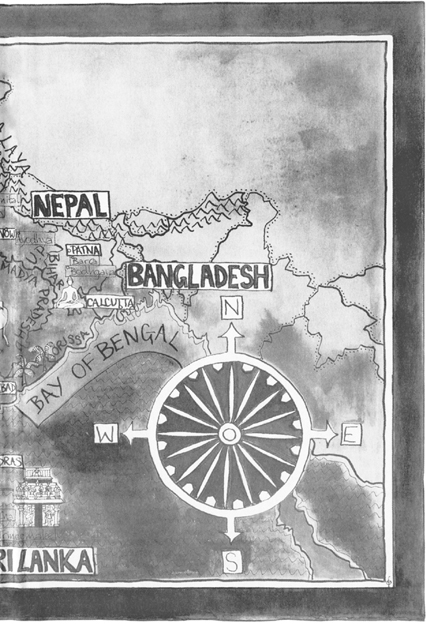

Map and illustrations 1998 by Olivia Fraser

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers, London, in 1998. Subsequently published in paperback in the United States by Lonely Planet Publications, Oakland, in 2000.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Departures and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress.

Cover design by Cardon Webb

Cover image Gianni Dagli Orti / The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

eISBN: 978-0-307-94893-9

v3.1

To

JOCK

who saw the point long before I did

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Age of Kali is a collection of peripatetic essays, a distillation of ten years travel around the Indian subcontinent. For six of those years I was based in Delhi working on my second book, City of Djinns, while for the other four I wandered the region, on a more nomadic basis, for a few months each year. My travels took me from the fortresses of the drug barons of the North-West Frontier to the jungle lairs of the Tamil Tigers; from flashy Bombay drinks parties to murderous Bihari blood feuds; from the decaying palaces of Lucknow to the Keralan exorcist temple of the bloodthirsty goddess Parashakti, She Who is Seated on a Throne of Five Corpses. All the pieces are the product of personal experience and direct observation.

The books title is a reference to the concept in ancient Hindu cosmology that time is divided into four great epochs. Each age (or yug) is named after one of the four throws, from best to worst, in a traditional Indian game of dice; accordingly, each successive age represents a period of increasing moral and social deterioration. The ancient mythological Golden Age, named after the highest throw of the dice, is known as the Krita Yug, or Age of Perfection. As I was told again and again on my travels around the subcontinent, India is now in the throes of the Kali Yug, the Age of Kali, the lowest possible throw, an epoch of strife, corruption, darkness and disintegration. In the Age of Kali the great gods Vishnu and Shiva are asleep and do not hear the prayers of their devotees. In such an age, normal conventions fall apart: anything is possible. As the seventh-century Vishnu Purana puts it:

The kings of the Kali Yug will be addicted to corruption and will seize the property of their subjects, but will, for the most part, be of limited power, rising and falling rapidly. Then property and wealth alone will confer rank; falsehood will be the only means of success in litigation. Corruption will be the universal means of subsistence. At the end, unable to support their avaricious kings, the people of the Kali Age will take refuge in the chasms between mountains, they will wear ragged garments, and they will have too many children. Thus in the Kali Age shall strife and decay constantly proceed, until the human race approaches annihilation.

In my travels in Pakistan and North India there were moments when it seemed as if the Kali Yug really was upon us. In the bandit-infested badlands north of Lahore, in Bihar and in parts of eastern Uttar Pradesh I found an ancient landscape overwhelmed by rapid change, where the old certainties and the ancient social order had been swept away, but where the new order had yet to fully establish itself. In Lucknow I witnessed a war being fought between rival wings of the student union, where each side was armed with grenades and assault rifles; in neighbouring Bihar, it seemed as if the state had finally succumbed to the tidal wave of violence, corruption and endemic caste warfare that had engulfed it. Indeed things were so bad that the criminals and the politicians of the state were said to be virtually interchangeable, and the government had pretty well given up any pretence of providing water, electricity or even a semblance of security. The state had given way, and Bihar now seemed to be approaching a situation of pure anarchy.

According to the Puranas, the Kali Yug is the last age before the world is destroyed by the fire of one thousand suns, after which the cycle reaches its conclusion and time momentarily stops, before the wheel turns again and a new cycle begins. Rather ominously, the very week I decided on The Age of Kali as the title for this book, Atal Behari Vajpayee, Indias first BJP Prime Minister, let off his Hindu nuclear bomb at Pokhran, in what some in India have seen as a sign that the Kali Yug is now approaching its apocalyptic climax. Following the blast, as ecstatic crowds filled the streets to celebrate and as some BJP activists set about trying to build a Hindu shakti temple on the site of the explosion several Indian papers quoted the lines from the Gita uttered by Robert Oppenheimer as he witnessed the first nuclear explosion at Alamogordo in 1945:

If the radiance of a thousand suns

Were to burst at once into the sky,

That would be like the splendour of the Mighty One

I am become Death,

The shatterer of worlds.

Yet for all this, India has consistently defied those who make prophecies of doom for her, and sure enough, outside Pakistan and the Ganges basin, in parts of the Deccan and southern India, I saw a world where notions of a Kali Yug seemed to have little relevance. In the far south and west of the country, despite occasional political upheavals in Tamil Nadu, there was a quiet but growing prosperity and stability that defied the grim predictions of imminent apocalypse being made in Patna and Lucknow. The great question for India now, it seems to me, is whether the prosperity of the south and west of the country can outweigh the disorder and decay which is spreading out from Bihar and the north.