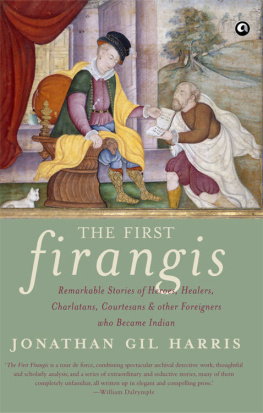

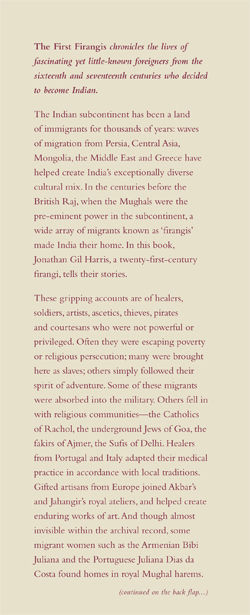

BOOKS BY JONATHAN GIL HARRIS

Foreign Bodies and the Body Politic: Discourses of Social Pathology in

Early Modern England

Sick Economies: Drama, Mercantilism and Disease in Shakespeare's England

Untimely Matter in the Time of Shakespeare

Shakespeare & Literary Theory

Marvellous Repossessions: The Tempest,

Globalization and the Waking Dream of Paradise

BOOKS EDITED BY JONATHAN GIL HARRIS

Staged Properties in Early Modern English Drama (with Natasha Korda)

The Shoemakers Holiday by Thomas Dekkar

Indography: Writing the 'Indian' in Early Modern Literature and Culture

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm

promoted by Rupa Publications India

First published in India in 2015 by

Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Copyright Jonathan Gil Harris 2015

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from Aleph Book Company.

eISBN: 978-93-83064-91-5

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

To Nikhil Armaan and Rohan Jannek,

who are also becoming Indian.

There is as much difference between us and

ourselves as there is between us and others.

Michel de Montaigne, The Essays

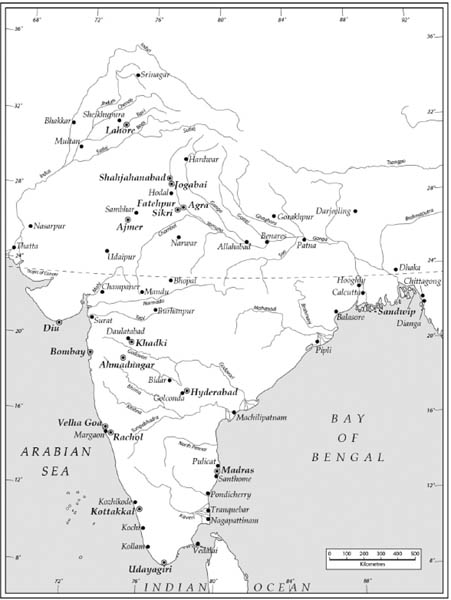

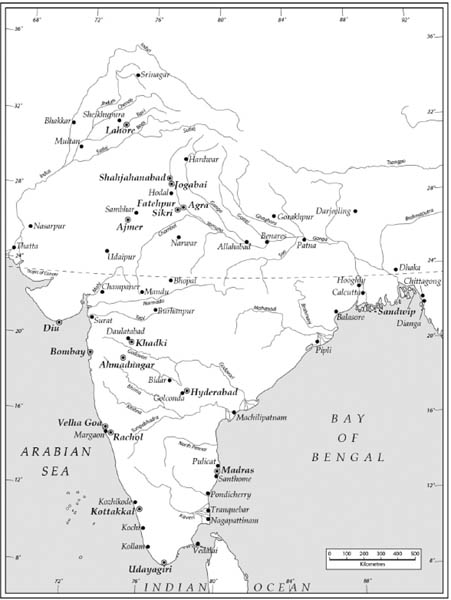

Indian subcontinent circa 1600-1700

CONTENTS

ON BECOMING ANOTHER

My body is not quite my body.

I like to think of it as mine. My dream of possession is really a dream of self-possession: our bodies, ourselves, as the old adage goes. But the fact is my body is never fully mine. It is constantly changing in ways I cant control. Not only does it age over time; it is also forever being modified by what it comes in contact with. Because I am writing this in a hot and humid room at the height of the Delhi summer, I am sweating and losing fluids. The namak nimbu paani I am drinking cools me and replenishes my depleted body salts; the light khadi cotton of my kurta lets in air that also keeps me from overheating. But in order to type these English and Hindi words, I have to rest my forearms on the surface of my hot laptopbaked both by the ambient air and Delhis electrical power surgesas a result of which my sweaty wrists are ringed by an increasingly angry heat rash. Are these my wrists anymore? Or are they the property of other entities: the hot laptop, the humid summer air, the cool fabrics of Indian clothes, the multilingual stew of north India?

My body is clearly not an unchanging unit. It isnt even a unit. That word suggests something self-contained and neatly divided from what is outside it. My body is, rather, an extension of the larger environment that I work in, against and with. As my environment changes, so does my body. And when my environment changes in extreme waysgeographically, climatically, gastronomically, culturally, linguistically, economicallymy bodys changes are most obvious to me. These changes never amount to full makeovers: wherever I go, my body carries with it the imprint of its past environments. But it is always becoming different in its new ones. It is always becoming another.

And here in India, I am becoming Indian. As have so many other migrants to the subcontinent before me. Our migrant bodies were not quite ours long before there was an independent or even a British India.

| BECOMING INDIAN; OR, THE TWO DAKAITS OF HODAL |

28 June 1656. Two dakaits (Hindi for bandits) approach a teenaged European boy in the scorching summer heat of Haryana. The bandits have spied him at the Hodal Sarai, some 90 kilometres short of Delhi on the imperial highway from Agra. The boy wears a glum expression; he keeps casting anxious glances at his luggage, which is far bulkier than we might expect of someone travelling alone. A runaway from Venice, he has been in India for just a few months. His name is Niccol Manucci. And he is in something of a pickle.

Manucci is the servant of an Englishman, Lord Bellomont, who had journeyed to India in the hope of meeting the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan. But three days into their journey from Agra to Delhi, without warning, Bellomont dropped dead. In the eight days since, young Manucci has had to fend for himself in unfamiliar and dangerous terrain. His wits have been expended on protecting his late masters belongings, which he cannot carry alone. In sum, Manucci is stranded at the sarai, unable to advance to Delhi or return to Agra.

The two dakaits smell Manuccis vulnerability. Dressed in Mughal clothes, they introduce themselves to him as captains in the army of Shah Jahan; one of them explains that they have instructions from the emperor to confiscate the property of the Englishman, which has now lapsed to the crown. Manucci asks to see official documentation authorizing the confiscation. None is forthcoming. He accuses the men of using Shah Jahans name as a ruse with which to steal other peoples property. At this, the dakaits start laughing like a pair of guffawing Bollywood villains. Predictably, they proceed to rob Manucci of all his late masters effects.

But heres the rub: the two Indian dakaits werent exactly Indian. Writing about the incident fifty years later, Manucci explains that this Mughal-era Gabbar Singh and Sambha were, in fact, two Englishmen named Thomas Roch and Raben Simitt. Forget Bollywood villains: the bandits, it seems, were really seventeenth-century predecessors of Michael Caines and Steve Martins con-artist characters in Dirty Rotten Scoundrelslow-life expatriates in a foreign country, preying on unsuspecting travellers through their skills of deception. Manucci damns the pair as two English impostors. But the imposture that exercises him is not their Indian disguise. Indeed, their dress doesnt strike him as being in any way abnormal, let alone deceitful. Manucci shrugs off what we might regard as the bandits most unusual feature, because Roch and Simitt had been truthful about one thing: they were indeed servants of Shah Jahan, part of a ragtag group of foreigners whom the emperor retained as mercenaries and who were obliged to wear Mughal clothes. What irks him, rather, was their fraudulence in claiming to act with the authority of the emperor, a major misdemeanourin Mughal eyes as much as Manuccis. Upon reaching Shah Jahans court in Delhi, Manucci lodged an official complaint against the emperors wayward employees, who were located and taken into custody.

Roch and Simitts story has haunted me for some time now. It is altogether different from the standard narrative about the British presence in Indiaa narrative of angrezi cultural, linguistic and racial supremacy, and of Indian oppression. Instead, Manucci presents us with the unexpected spectacle of two, presumably poor, Englishmen who were servants, if rather badly behaved ones, of the Great Mughal. I am fascinated as much by what Manuccis story leaves out as by what it includes. How had Roch and Simitt come to be in Hindustan? What drove them to seek service with Shah Jahan? If they wore desi clothes, what other aspects of Mughal Hindustani culture had they assumed? Did they eat English food or Mughlai khana? When speaking with the Italian Manucci, did they resort to English, another European tongue, the local Hindavi dialect of the north, or Persian (the language of the Mughal court, in which Manucci was already partly fluent after spending some years in Iran)? And what happened after their punishmentdid they remain in India and, if so, did they have Indian partners and even children? In short, to what extent did they become Indian?