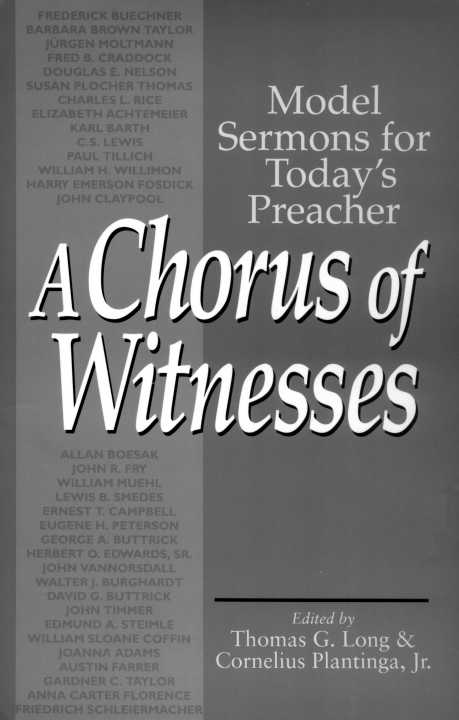

A CHORUS OF WITNESSES

A Chorus of Witnesses

Model Sermons for Today's Preacher

Edited by

Thomas G. Long and Cornelius Plantinga, Jr.

For all the gospel preachers everywhere. Especially, for all the gospel preachers who, drawing the short straw, were summoned to preach in our earshot in Michigan and Georgia in the seasons of our youth, and who, despite our adolescent smirks and our hard hearing, managed to get through our dullness with the grace of God.

Contents

x

xii

Editors' Preface

We have chosen, arranged, and introduced the sermons of this volume in the hope that people will ponder, inspect, disassemble, praise, criticize, and, generally, learn from them. (Some of these sermons pack enough of a spiritual wallop that they will also edify readers.)

Our hope rises from the conviction that just as aspiring composers study Haydn symphonies and Bartok string quartets, just as serious chess players learn the great games of Tarrasch and Capablanca, just as army generals master the battle plans of strategic and tactical experts from Alexander the Great to Douglas MacArthur, so students of preaching must study great sermons, learn their moves, and master some of their aims and forms. No seminary ought to launch new preachers who are still cheerfully ignorant of Buechner and the Buttricks and Barbara Brown Taylor and Gardner C. Taylor and other experts. The primary intended use of this volume is therefore to accompany homiletics texts in seminary preaching courses.

But we also have others in view. Shouldn't most established preachers spend a week a year tuning their ears and untethering their imaginations by reading and pondering some crackerjack sermons? And how about mere Christians who want to love God with their whole minds and hearts, and who are always looking for writers to help them do it?

This volume is for such folk and, accordingly, for us.

We want to thank Scott Black Johnston and David M. Rylaars- dam, who have assisted us at every stage of this project.

Introduction

A Chorus of Witnesses presents thirty-six sermons that display an array of excellences in form, style, and content. All but one (Schleiermacher's "Sermon at Nathanael's Grave") are by twentieth-century preachers, many of them our contemporaries. Some are by regular church ministers, some by theologians, some by chaplains, and several, not surprisingly, by homileticians. One is by an Oxford literature professor who became famous as a religious writer. The preachers of these sermons are Christian men and women, Europeans, South Africans, Americans, Canadians, and African-Americans. They are Lutheran, Reformed, Catholic, Methodist, Baptist, and Anglican Christians of particular religious ethos and habits of heart.

Accordingly, the sermons vary in lots of ways, including in their theological and hermeneutical commitments and in their attachment to texts. But each offers features of particular interest to preachers, aspiring preachers, and general Christian readers.

We have assembled the anthology to capture these features and have sectioned it to display them. In the four sections readers will find sermons that make artful use of their sources, that pursue classic aims, that exhibit particular homiletic forms and dynamics, and that fit special occasions.

We know that a number of the sermons in the anthology could just as well have appeared in some other section than the one we chose. For instance, though we have placed Barbara Brown Taylor's sermon in the "Sources" section to illustrate an intelligent following of a biblical trajectory, we might have used it as a section three ("Forms and Dynamics") sermon for its fine use of imagery and of a central waiting-in-line analogy. Similarly, John Claypool's "Life Is a Gift" appears in the "Aims" section, because it is a sermon that attempts to deliver pastoral care. But it is also a father's expression of grief, and it might therefore have appeared with the three funeral sermons (no apology for the piling up of riches here) under the heading of "Occasions."

So the sermons in the anthology may model virtues besides the ones we have chosen to highlight. They may also model vices we have chosen not to highlight. Readers are likely to judge that a given piece serves as a model in some respects and as an anti-model in others. For instance, readers may reject the theology of a sermon whose form they admire. Or they may approve a sermon's aim but not its means of achieving it. Or they may wince at the way a sermon handles its text but find their hearts strangely warmed by the sermon itself. Perhaps homiletic discernment, like general spiritual discernment, is a gift of the Spirit. In any case, serious study of widely varying sermons is likely to sharpen it - and this is so whether such discernment is sheerly given, or acquired by hard work, or, like so much else that is excellent and of good report, by some combination of these means.

Of course, a written sermon is not a preached sermon. Reading a sermon is an importantly different experience from hearing one, and both differ from actually seeing a preacher aim and fire. So, understandably, some written sermons do not do their authors full justice. Lewis Smedes's "The Power of Promises" shivers the bones in its taped version not only because of Smedes's Olympic level of thought and diction but also because of wonderful things he does with crescendos and accelerandos and sforzandos and shadings of timbre. Predictably, the written version preserves the former virtues but not the latter. That is the simple limitation of the genre.

On the other hand, as anyone knows who has heard a tape of Winston Churchill's great World War II speeches, it is quite possible to utter something of nearly final magnificence with a slightly slurred matter-of-factness. Some sermons are better to read than to hear because in the preaching of them their own authors manage to diminish or even to sabotage the sermon by a bland or foolish or otherwise distracting delivery.

Reading a fine sermon is like reading the score of some musical masterpiece. Whether reading a piece is better or worse than hearing it depends in part on the quality of the performance. In any case, reading allows you to stop the machinery so that you can inspect it.

A word on the biblical texts that appear at the heads of most sermons: we have not supplied or inferred any texts, but we have taken the liberty of printing out a number of texts (in RSV, except where otherwise noted) that sermon authors had merely cited. Naturally, we have republished texts that originally appeared in full quotation. Those, too, are all RSV unless otherwise noted.

THE SOURCES

OF THE SERMON

Every sermon at least extends and amplifies its source; many sermons do much more. They imaginatively embellish a text, for example, or explain it, or do the second by doing the first. They publicly ponder the text, turning it this way and that, questioning it, conversing with it. They may juxtapose one text with another, letting the two cross-fertilize each other. Some sermons completely reset a source's context. They change all the drapes and upholstery around a text in such a way that, like an old piano in a newly remodeled room, the text suddenly sounds different to us.

One of the sermons in this section seemingly ignores its biblical text until the sermon is nearly done. Then, late in the day, the text speaks with special poignance.