Copyright 2004 by Ed Willes

Cloth edition published 2004

Trade paperback edition published 2005

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Willes, Ed

The rebel league : the short and unruly life of the World Hockey Association / Ed Willes.

eISBN: 978-1-55199-600-4

1. World Hockey Association History. I. Title.

GV 847.8. W 67 W 54 2004 796.96264 C 2004-902521- X

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M 5 A 2 P 9

www.mcclelland.com

v3.1

This book is dedicated to: the memory of Doug Michel,

John Bassett, and Al Smith; the hockey fans of

Winnipeg, Quebec, and Hartford; and that little bit

of the WHA that lives inside all of us.

CONTENTS

ONE

They knew nothing about hockey. Absolutely zero.

TWO

Howd you like to come play for me in Winnipeg?

THREE

Youll rue the day you got all this money.

FOUR

It brought the love of the game back to me.

FIVE

We had every idiot who ever played.

SIX

You just saw things in the WHA you never saw anywhere else.

SEVEN

It was too much, too soon.

EIGHT

They brought the Quebec flag with them everywhere they went.

NINE

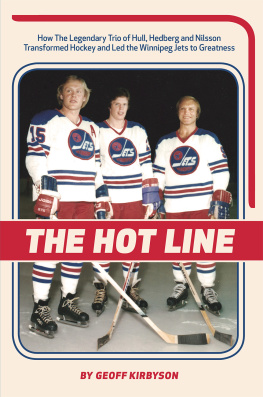

It was one of the greatest lines to ever play the game.

TEN

They provided some beautiful moments.

ELEVEN

He surprised me. He surprised everyone. Forever.

TWELVE

The thing people dont understand is the dream and how powerful it is.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are several people Id like to thank for their immeasurable contribution to this book. My wife, Kathy, for making all things possible. J. P. and Robert, for their inspiration. Ed and Bernice Willes, for their unwavering support. Owen and Pat Kealey, for all their help. Warren, Graham, and Domenic, for their friendship. And all the Willeses and all the Kealeys, for the bonds of family.

On a professional level, Id like to extend a sincere thank-you to Vivienne Sosnowski, Malcolm Kirk, Wayne Moriarty, Paul Chapman, and Erik Rolfsen at the Vancouver Province; Kevin Paul Dupont of the Boston Globe, who interviewed Derek Sanderson, Gerry Cheevers, and John McKenzie; Jason Kay and Mark Brender at The Hockey News, for providing invaluable resource material; Jim Matheson and Terry Jones in Edmonton, Philippe Cantin and Michael Farber in Montreal, and Roy MacGregor in Ottawa, for their pro bono proofreading; and Jim Coleman, Dave Anderson, George Vecsey, Stephen Brunt, Cam Cole, Al Maki, and Al Strachan, for sending the elevator back down.

INTRODUCTION

I n 197879, the last season of the World Hockey Associations rich seven-year life, Quebec Nordiques coach Jacques Demers had to dress for a pre-game warmup to ensure his team met the leagues minimum player requirement.

Demers, who coached four different WHA teams without ever being fired, doesnt see anything odd in that. The year before, Demers, then coach of the Cincinnati Stingers, had to bail Frankie Beaton of the Birmingham Bulls out of jail in Cincinnati after Beaton was arrested on a three-year-old warrant. His reaction is the same. No big deal. Demers started his WHA coaching career in Chicago, where the Cougars played out of the Chicago Amphitheater, a dank, decrepit old barn that was located near the stockyards and tended to smell of rotting animal flesh. The old coach still regards it as the luckiest break of his life.

We did what we had to do to survive, says Demers, who would go on to coach in the NHL for fourteen years and win a Stanley Cup with the Montreal Canadiens in 1993. That was one thing about the WHA , we were all trying to pull together for the league.

If theres a theme that runs through the history of the WHA , its survival. Players, coaches, and owners were all stakeholders in the grand adventure Dennis Sobchuk, who played in both leagues, says the biggest difference between the NHL and the WHA was that in the NHL you never saw the owners, in the WHA you drank with them and all were committed to doing whatever was necessary to keep the league alive. It didnt matter if a payroll was missed. It didnt matter if the franchise folded. It didnt matter if bills went unpaid and the sheriff was at the door.

In the WHA you just tried to make it to the next game.

It was a way of life with us, says Gerry Pinder, who played five-plus seasons in the WHA . We knew wed taken some risks coming into the new league. But it wasnt a panic situation, because we felt like pioneers. We were doing something no one else was prepared to do.

Its interesting to note, then, how that same theme of survival has continued to run through the lives of so many of the WHAS players and hockey men long after the league folded. Bill Goldthorpe, who lived like Stagger Lee, was shot and wounded, he says, while trying to protect a woman. While he was in the hospital convalescing, his father died. Upon his release, Goldthorpe went back to school, took accounting and computer-programming courses, and now works as a construction foreman in San Diego.

In the summer of 1998, the hot-water heater exploded in the Pointe-du-Chene, New Brunswick, home Gordie Gallant shared with his partner, Debbie McFadden. Gallant, who also served in the Canadian army, suffered burns to 80 per cent of his body while saving McFadden and her seven-year-old son, and went into a coma. Given the last rites on two different occasions, he spent five months in the burn unit at the Moncton hospital and underwent nine operations. Today, hes back playing oldtimers hockey.

In December 1999, Paul Shmyr was diagnosed with cancer of the throat and given three months to live. Instead of accepting the death sentence, he started networking with other cancer patients and was led to a hospital on Staten Island that offered an aggressive treatment called stereotactic radiation. The sessions were paid for in large part by the NHL Emergency Fund and the NHL Alumni Association. In the fall of 2003, Shmyr celebrated his return to the Vancouver Canucks oldtimers. I tell the guys on the oldtimers team its costing them a lot to keep me around, Shmyr said at the time. But its worth it because I make the power play go.

Shmyr passed away shortly before this book was published. The treatments bought him five years and he was fighting right until the end. Cancer is pretty tough, hed say, but its never fought a Shmyr. Everywhere he went, the guys liked him, said Al Hamilton, Shmyrs teammate in Edmonton. He had a great sense of humour and everything was a lot of fun when he was around. But he was also as tough as they come and he absolutely maximized his abilities.