All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Faber & Faber Limited, London, in 2018.

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Atkins, William (Editor), author.

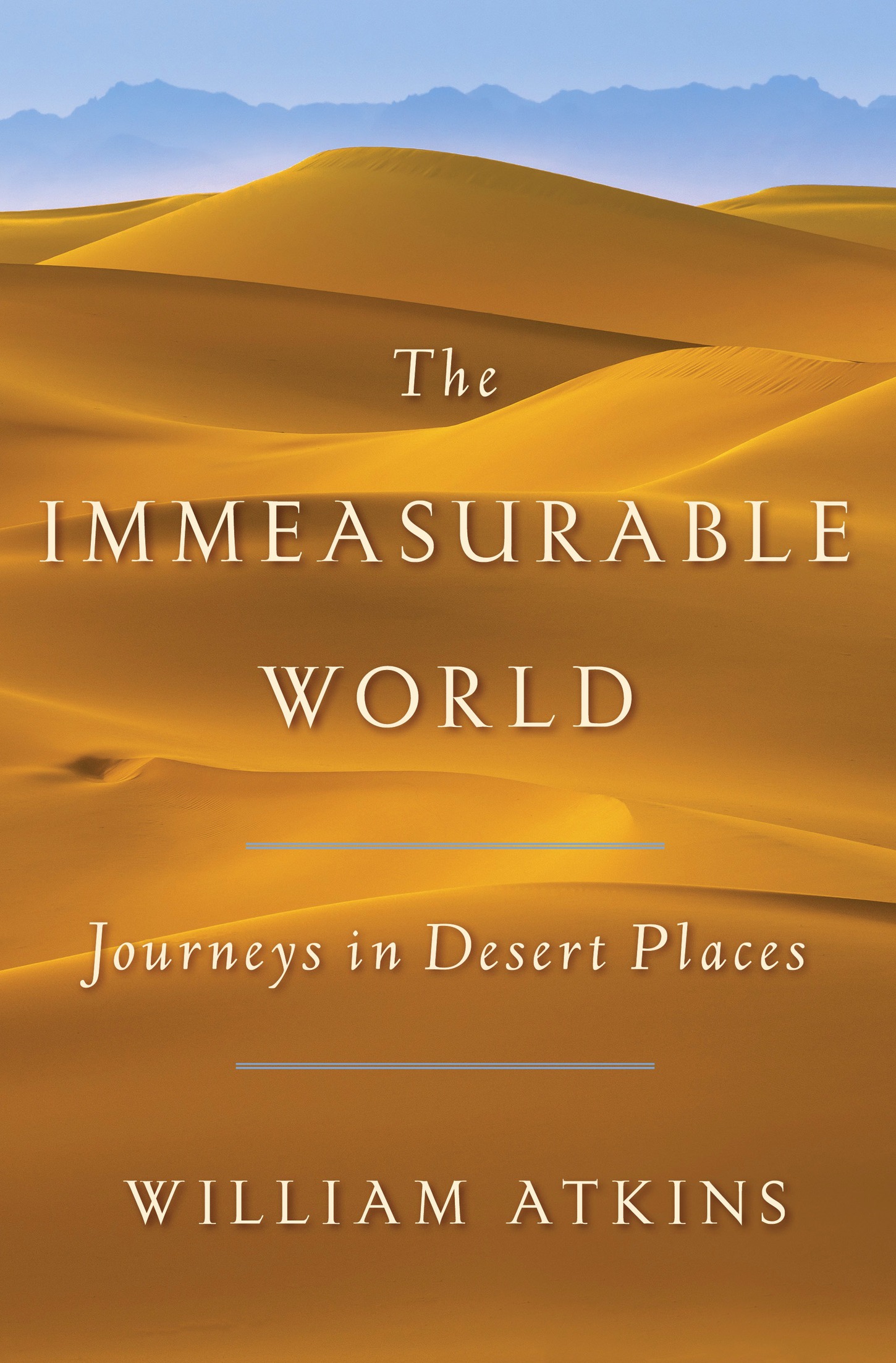

Title: The immeasurable world : journeys in desert places / William Atkins.

Description: New York : Doubleday, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017053583 | ISBN 9780385539883 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385539890 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Deserts. | Atkins, Will (Editor)Travel. | BISAC: TRAVEL / Special Interest / Adventure. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | HISTORY / Historical Geography.

Classification: LCC GB611 .A85 2018 | DDC 910.915/4dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017053583

Three days its been without a trace of him, his nag, his leather shield, his lance or his armourIts my belief, as sure as I was born to die, that his brains been turned by those damned chivalry books of his he reads all the timeI remember often hearing him say to himself that he wanted to be a knight errant and go off in search of adventures. The devil take all those books, and Barabbas take them too, for scrambling the finest mind in all La Mancha!

P ROLOGUE

I t was the night of the blood moon. The term was coined by Bible Belt millenarians who believed the phenomenona lunar eclipse when the full moon is at its perigee, therefore magnified and pinkportended Armageddon. Joel 2:31: The sun shall be turned to darkness and the moon to blood before the great and dreadful day of the Lord comes. The timing was just good fortune but it turned out Id have among the best views on earth. In my ignorance it was its redness I anticipated as much as its bigness or for that matter the fact that it would be eclipsed, and so when it rose into view, more embers than blood, I was disappointedas disappointed as one can ever be by a new-risen full moon.

By the time Id rehydrated my noodles and poured my daily half-beaker of wine, the moon had returned from grey-pink to its customary white, like a fingertip pressed against glass, and every cactus and every shrub, and the strawbale cabin, had generated a hard exclusive shadow. It seemed to me that the chief characteristic of night in the desert was not darkness but this light that was not the suns.

THE CABIN STANDS on a ridge above the San Pedro River sixty kilometres east of Tucson, Arizona. It is a one-room structure about three metres by five, with a door facing north-east. In each of the other three walls is a single window, screened with mesh against insects. Its nice to open the windows to the evening breeze, but during the day they stay shut to keep out the heat. The interior walls are thickly plastered, bumpy and cracked. The floor is packed earth laid with two rugs heavily nibbled by mice. Furniture: a cabinet for cooking utensils, a folding steel cot and mattress, a pine table and matching chairs, and an iron-banded trunk a century old, containing Mexican blankets, batteries and a first-aid kit and dozens of candles. The table resembles an altar. On it, most of the time, stands a storm lantern and a bottle of screw-top Cabernet Merlot ($8.99, Trader Joes).

Each of the four windows (theres one in the door) gives onto a hillside thick with mesquite, paloverde, creosote bush, ocotillo, prickly pear, barrel cactus, and saguaro, the regions characteristic cactus, the cactus of cowboy films. It is the saguaros giant candelabra forms that break the line of each hillside and provide landmarks. The tallest for kilometres stands beside the cabin. From the south-west-facing window you can see the Rincon Mountains, with the Little Rincons before them, dropping down to the San Pedro Valley, and the few dwellings of the Cascabel community ten kilometres away. When the sun rises behind me, a blade of light drops from the distant peaks of the Rincons, down the foothills and towards me across the alluvial plain, until slowly, like a lava flow, the threshold where light meets shadow approaches the cabinand then: there! The warmth as the suns rays touch the back of my head and my shadow is thrown down long before me.

From a hook fixed to a rafter-end I hang a kettle of water on a bungee each morning, and by 6 p.m. it is hot enough for a shower. On the cabins opposite side, where there is more shade, lies the two-hundred-litre drum that provides all my water, raised on a bed of rocks and protected against the sun with a jacket of wire-strung saguaro ribs.

The ridge separates two washes (dry, except after cloudbursts): one is broad and shallow, the other is deep and narrow and what they call an arroyo. The ridge rises to the north-easthalfway up this hill, about thirty metres from my door, is a double wooden frame into which two identical square boards are slid, each painted white on one side and on the other red. Every evening, before my shower, though I dont always remember, I walk up the hill along a path marked out with rocks on each side, and slide out the boards, flip them over, and slide them back into the framework. From the ridge near his home down near the San Pedro, my friend Daniel checks each morning with his binoculars, if he remembers; if the boards do not change for a day or two, hell come and make sure Im okay.

There are a few books here: a natural history of the Sonoran Desert and a book about the dangerous animals of the region, every one hair-triggered, youd be forgiven for inferring, to sting you, bite you, maul you, or char you with its fiery breath. My own contribution is a paperback facsimile of John C. Van Dykes 1901 book The Desert. It describes a mans journey, alone, into this desert, the Sonoran, a journey made chiefly in 1898, though its precise course is unclear. He was an accomplished art historian, but trust Van Dykes guidance at your peril. Here he is, homicidally, on the subject of food and water, for instance: Any athlete or Indian will tell you that you can travel better without them. They are good things at the end of the trip but not at the beginning. Rattlesnakes he describes as sluggish. He shoots grey wolves in California, where there were no wolves, and eulogises the purple flowers of the saguaro, which are white (though the fruits are red). Alerted to certain errors by a well-meaning desert ecologist, he graciously acknowledged the mistakes, promised to correct them in future editionsThe Desert had a long lifeand so far as is known made no effort to do so. A note appended to the manuscript of his autobiography spells out his aim: to describe the desert from an aesthetic, not scientific, point of view.

I no longer sleep inside but, after my sunset shower, drag the cot out to the clearing in front of the door, where I am not disturbed by the lizards in the roofor, more accurately, where the noise they make is subsumed by the larger racket of the desert at night. I lift each of the beds feet and slip containers of water under themtin mugs, a wooden saucer, a saucepanto keep conenose kissing-bugs or scorpions from joining me. I position the two chairs beside the bed, one at the foot, one alongside my head, and stand lanterns on them. In a row on the ground between them half a dozen candles are stationed. In the mornings the hardened wells around their wicks are black with flying insects. Within this lit perimeter I sleep more easily than I have for months, which is not to say deeply. Waking in the night to the buzzing of cicadas or the yapping of coyotes, I experience a weight of tranquillity that has the quality of a quilt. It might be the peace of the dying.