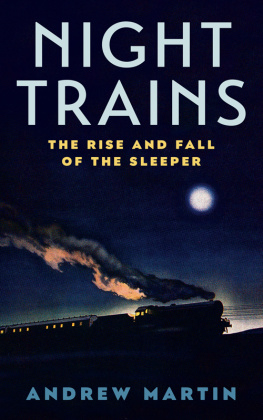

NIGHT TRAINS

ANDREW MARTIN is a journalist and author. His previous books for Profile include Underground, Overground and Belles and Whistles. He has written for the Evening Standard, Sunday Times, Independent on Sunday, Daily Telegraph and New Statesman. His Jim Stringer series of novels based around railways are published by Faber. His latest novel, The Yellow Diamond, is set in the world of Londons Super-rich.

ALSO BY ANDREW MARTIN

NON-FICTION

Belles & Whistles (Profile)

Underground Overground (Profile)

How to Get Things Really Flat

Ghoul Britannia

Flight by Elephant

FICTION

In the Jim Stringer series

The Necropolis Railway

The Blackpool Highflyer

The Lost Luggage Porter

Murder at Deviation Junction

Death on a Branch Line

The Last Train to Scarborough

The Somme Stations

The Baghdad Railway Club

Night Train to Jamalpur

Bilton

The Bobby Dazzlers

The Yellow Diamond

Soot (forthcoming)

NIGHT TRAINS

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE SLEEPER

ANDREW MARTIN

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Andrew Martin, 2017

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 212 6

The following passage is from Railway Wonders of the World magazine, October 1935. I intended to quote it ironically as soon as an official of one of the modern sleeper trains annoyed me:

It is no exaggeration to say that the popularity of the International Sleeping Car Company is partly due to the travelling officials in their smart brown uniforms (the dining car waiters wear immaculate white jackets). They deal daily with a large number of passengers belonging to all nations of the world, where each has his own peculiarities and requirements, expressed in many different languages. The passengers may consist of Royalties and crooks, artists and millionaires, diplomats and spies, scientists and generals, old ladies and film stars, infants in arms and death-defying octogenarians, thrown together within the narrow space of the railway carriage. To deal daily with such a kaleidoscopic multitude demands iron nerves, endless tact and an eternally good humour.

In the event, the passage was never required (which is not to say that all my journeys went smoothly), so I dedicate this book to the men and women who operate the surviving European sleepers.

INTRODUCTION

THE BLUE CARRIAGES AND ME

My father not only worked for British Rail (BR), he also believed in the railways, in spite of their unfashionability during most of his career. His enthusiasm probably owed something to the fact that he was entitled to free train travel at home and in Europe. He was one of those who took advantage of that European perk, and he was a member of the British Railwaymens Touring Club (BRTC), which organised group holidays for BR workers and their dependants.

For three successive summers, between 1973 and 1975, my father, my sister and I (my mother had died in 1971) convened on what the BRTC men called the main up platform of York station, and what normal people called platform three, to wait for a London train. We were on our way to the Continent, a term implying a certain remoteness that began to fall out of use when Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973. Twice we went to Lido di Jesolo in Italy, once to Lloret de Mar in Spain. In the weeks before departure, my father, a Europhile, had been briefing me about the holiday ahead. He described the continental breakfast that awaited, which I was particularly excited about even though considered objectively it was bread and jam, albeit with real orange juice. (The orange juice is a cocktail, my dad counselled, you sip it.) He also held out the exciting prospect of an unusually thin soup called consomm (in which one put, strange as it may seem, grated cheese) while warning of very strong coffee served in very small cups, and a complete absence of tea.

I recall the cluster of suitcases on the York platform, the patterned summer frocks of the women, some of whom already had their sunglasses on. They took a maternal interest in my sister and me: Now you have brought your sunhats, havent you? I remember the freshly whitened plimsolls of the men, and the BRTC badges on the lapels of their summer jackets. The badge was circular, with the countries of Europe west of Russia shown in gold against a blue background. In the absence of my father, who died as I began writing this book, I might think Id dreamt our railway jaunts were it not for that badge, which is the only thing that comes up when the words British Railwaymens Touring Club are put into the Internet. (The badges are offered for sale on various sites, with suggestions for starting bids around the three pound mark.)

The National Rail Museum in York reported no mention of the BRTC on their database, and suggested I contact an organisation called REPTA. This used to stand for Railway Employees Privilege Ticket Association, a name that expressed the pride of the railwaymen of the 1920s, who had fought for travel concessions, and formed an association to protect them. Today, nobody calls themselves privileged, and the organisation has become the Railway Employees & Public Transport Association. According to its spokesman, Colin Rolle, it is a benefits association for active and retired railwaymen, but the retired BR staff remain more privileged than those currently employed, who have concessionary travel within Britain only on the territory of their train operating company, and must clear high bureaucratic hurdles to access less generous European concessions than were enjoyed by my dad. According to Colin Rolle, The British Railwaymens Touring Club wasnt part of British Rail. It was an independent tour company that organised package holidays for railwaymen, using their free travel. We dont have any mention of it in our records, but I think it folded in the early 80s.

Now back to York station in 1973. When the train came in, I concentrated on looking nonchalant as we headed for first class. As a fairly senior man on the salaried side (as hed modestly say), my fathers privilege tickets were all firsts. We arrived at Kings Cross The Cross to the BRTC men at lunchtime. From there we transferred to Victoria by Underground. (The BRTC men had free travel on that as well, and I was always disappointed that there was no first class on the Tube, because if there had been, wed have been in it.) At Victoria, we entrained for Dover. We then took a ferry operated by Sealink, the seagoing arm of BR. This we boarded at blustery Dover Marine station, which was located directly on the dock, and offered the classic conjunction of the boattrain era, which now seems dreamlike: a railway station with a ship alongside. It was customary for the railwaymen to point out to us children that the BR double arrow appeared the right way round on one side of the ferrys funnel, while being reversed on the other side so as to resemble an S for Sealink.

Next page