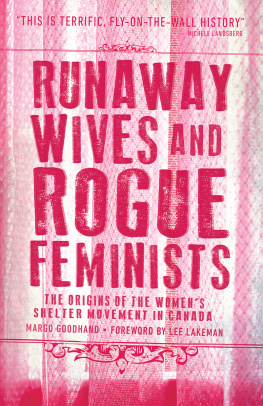

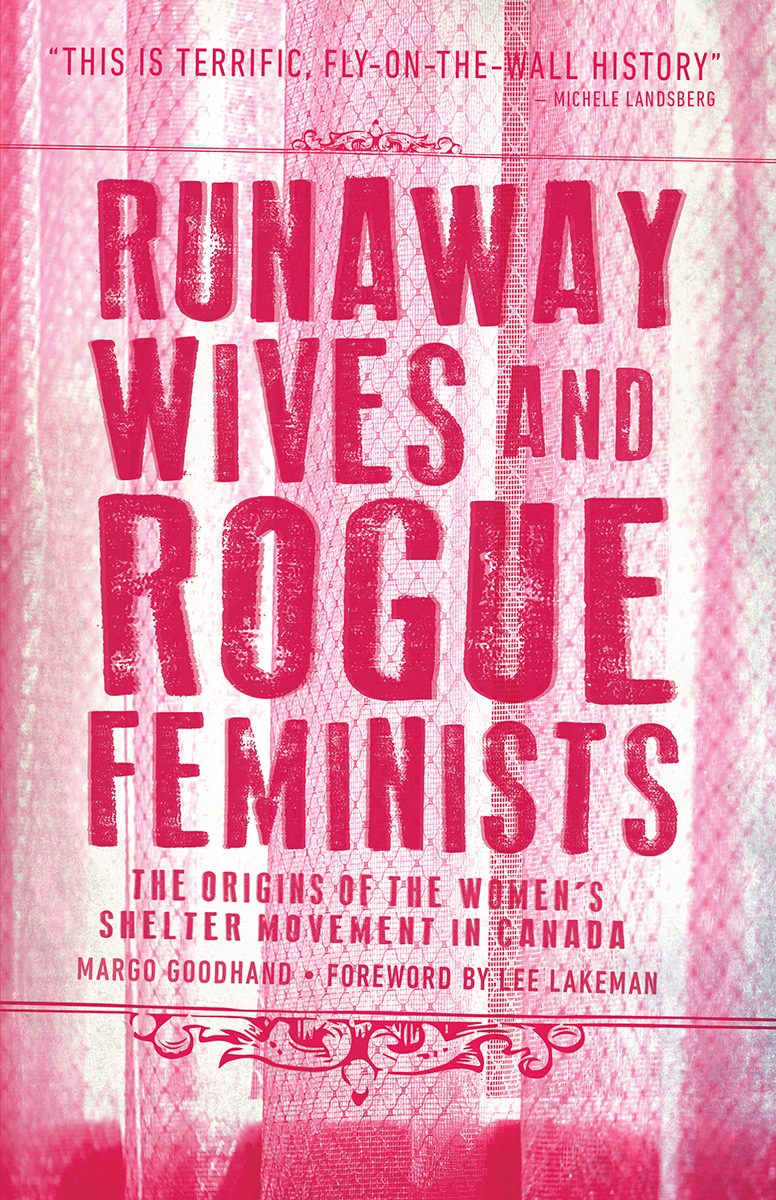

RUNAWAY

WIVES AND

ROGUE

FEMINISTS

RUNAWAY

WIVES AND

ROGUE

FEMINISTS

THE ORIGINS OF THE WOMENS SHELTER MOVEMENT IN CANADA

MARGO GOODHAND FOREWORD BY LEE LAKEMAN

FERNWOOD PUBLISHING

HALIFAX & WINNIPEG

Copyright 2017 Margo Goodhand

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Editing: Brenda Conroy

Cover design: Jess Koroscil, Housefires Design & Illustration

Printed and bound in Canada

eBook: tikaebooks.com

Published by Fernwood Publishing

32 Oceanvista Lane, Black Point, Nova Scotia, B0J 1B0

and 748 Broadway Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3G 0X3

www.fernwoodpublishing.ca

Fernwood Publishing Company Limited gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada, the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Tourism under the Manitoba Publishers Marketing Assistance Program and the Province of Manitoba, through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, for our publishing program. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Province of Nova Scotia to develop and promote our creative industries for the benefit of all Nova Scotians. We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Goodhand, Margo, author

Runaway wives and rogue feminists : the origins of the womens shelter movement in Canada / Margo Goodhand.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55266-999-0 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77363-000-7

(EPUB).--ISBN 978-1-77363-001-4 (Kindle)

1. Womens shelters--Canada--History. 2. Abused women--Services for--Canada--History. 3. Feminists--Canada--History. 4. Women--Canada--History. I. Title.

HV1448.C3G66 2017 362.83830971 C2017-903104-X

C2017-903105-8

CONTENTS

This book is dedicated to the women who founded our rape crisis centres and womens shelters, and to those who continue to work there, in obscure and often dark places. They are rich only in the knowledge that they make a difference, every day.

For their courage and grace, we salute them.

FOREWORD

THE ENVY OF THE WOMENS MOVEMENT

DURING THE SECOND WAVE of feminism, women in Canada developed a system of womens shelters and transition houses that remains the envy of womens movements around the world. Ive been invited to tell about it in cities as far afield as Moscow and New Delhi. Neoliberalism has damaged that heritage but it remains true that every major city and most small towns and even some tiny remote communities can boast a small enclave, a woman-guarded spot, a life-saving refuge, free from the quotidian dangers of male violence against women. Most are also centres of learning and organizing against unfair administration of law, unfair economics and unfair social practices that limit the freedom of women.

The Goodhand sisters start with a simple question of who and when were the pioneers of the first five Canadian transition houses. But the answers are not so simple. First in the country, first open or first continuously open, first funded, first full? Not to mention the question of who to credit: those who had an idea and worked the political system? Or those who first stepped through the doors to work overnight shifts, cook with distressed women, care for distracted children, fend off enraged men?

The evidence they found shows some things very clearly: it was women, in groups, struggling to provide a place to go, a way out, an interval, an emergency shelter in which other women and their children could hide, think and strategize. Most saw themselves as womens libbers or feminists. Most were ordinary women, neither highly politicized nor credentialed nor moneyed. They ranged in age and class and race, and so did the women they sheltered. But shelter was not the only objective. Their belief was that women would, while they lived together in the houses, find hope in feminism as we did, and would aid each other to cope and to move on to a better freer life. And they did.

One of my fond memories in the Woodstock Womens Emergency Centre was of a nurse who decided to escape from a violently abusive drunkard with her five children. She could work part-time but still had young ones, so cash would never be plentiful. She had worked hard to build a life that was wholesome and healthy for her children and she was determined not to give that up. Once temporarily safe in our house, she began to plot and scheme with other women in transition. She was determined. Against all odds, she found a farm house to rent in another part of the county. Then she and other residents arranged the test-drive of a van for sale at a local dealership. Without telling me (they thought it might be illegal and the reputation of staff should be protected for the sake of other women) and without telling the dealership (for obvious reasons), they drove to her former home, where her belligerent ex-partner was predictably passed out. In the dark of an Oxford County autumn, the women silently walked the goat, the piglets, the chickens and the cat through six-foot high corn stalks to that van, and moved the whole lot plus hay bales and tools lock-stock-and-barrel to the new farm. The women returned to the shelter, mission accomplished, but only after successfully returning the van one serious car wash later.

I remain in touch with many women who came through our houses as workers and residents. Im sure many of the pioneers do, too. This book celebrates the work in which they individually and collectively imagined, invented and supplied the Canadian transition houses.

Lee Lakeman

Lee Lakeman established the Woodstock Womens Emergency Centre in her home in 197374, and has worked at Vancouvers Rape Relief and Womens Shelter for forty years. She is writing a history of the organization.

PREFACE

A TRUE STORY, NOT YET TOLD

I GREW UP IN a world where women, by and large, didnt make history. My Grade 10 social studies textbook was memorably titled Man and His World . Apart from a few references to Laura Secord or Nellie McClung, history appeared to be written solely about and by men.

I remember thinking that if I ever grew up to write a book of my own, it would be about women: a good story, a true story, one that hadnt yet been told.

While I was editor of the Winnipeg Free Press in 2011, my sister Joyce noted one day that she had always wanted to document Canadas womens shelter movement, which began in the early 1970s. She feared this important piece of history would be lost as its pioneers died off. She knew firsthand that everyone in the field is too overworked and underfunded to take the step themselves. She had helped found Swift Currents first shelter in 1989 and was then working for the fledgling national network of shelters and transition houses in Ottawa.

It was a eureka moment for both of us, discovering a project we could work on together. And it became particularly intriguing when we discovered that Canadas first battered womens shelters all opened in the same year 1973. How could five separate groups of women, from big-city Toronto to sleepy little Aldergrove in B.C. in the days before the Internet, all under different political systems, all unbeknownst to each other just suddenly make this thing happen? How and why did these five disparate groups of women, from the self-described pot-smoking hippies to desperate single moms on welfare get together in the first place? And how with no experience in a field that did not yet exist did they convince anybody anywhere to give them funding?