* * * *

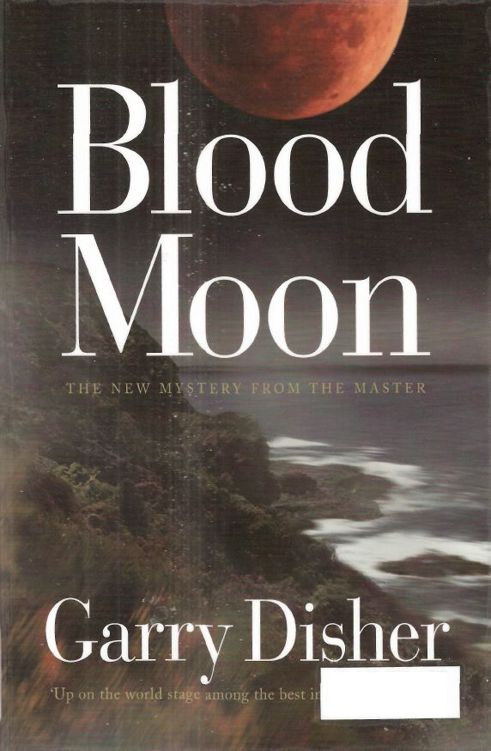

Blood Moon

[Inspector Challis05]

By Garry Disher

Scanned & Proofed By MadMaxAU

* * * *

Ona Tuesday morning in mid-November, late spring, the air outside the bedroomwindow warm and pollinated, Adrian Wishart watched his wife urinate. Hehappened to be sitting on the end of the bed, dressed, comb tracks in his hair,tying his shoelaces. She was in the ensuite bathroom, perched naked on the loo,wearing the long-distance stare that took her so far away from him. She didntknow she was being observed. She tore off several metres of toilet paper,patted herself dry, and as the water flushed it all away he came to the doorwayand said constrictedly, Were not made of money.

Ludmilla started and gave him ahunted look. Sorry.

Folding in on herself, scarcelymoving, she opened the glass door to the shower stall. He rotated his wrist,tapped his watch face. Im timing you.

Little things, but they cost money.No one needed a long shower. No woman needed that much toilet paper. No need toleave a light on when you go into another room. Why shop for groceries three orfour times a week when once would do?

Adrian Wishart watched his wife turnher shoulders under the lancing water. It darkened her red hair and streameddown her bodya body a little heavier-looking in the thighs and waist, hethought. She was doing her daydreaming thing again, so he rapped on the glassto wake her up. At once she began to work shampoo into her hair.

Wishart slipped out of the ensuite,out of the bedroom, and made his way to the hallstand where she always stowedher handbag. Purse, mobile phone, tampons, one toffeeso much for herdietdiary and a parking receipt that he checked out pretty thoroughly: aparking station in central Melbourne, maybe from when shed attended thatplanning appeals tribunal yesterday. He unlocked her phone, scrolled throughcalls made, stored text messages, names in her address book. Nothing caught hiseye. He was running out of time or hed have fired up her laptop and checked here-mails, too. Then again, she had a computer at work, and who knew what e-mailsshe was getting there.

Her little silver Golf sat in thecarport, behind his Citroen. The odometer read 46,268, meaning that yesterdayshed driven almost 150 kiLornetres. He closed his eyes, working it out. Theround trip between home and her office in Waterloo was only seven kiLornetres.That meant one thing: instead of driving a shire car up to the appeals tribunalin the city yesterday, shed driven her car.

Their house was on a low hill abovethe coastal town of Waterloo. He stared unseeingly across the town to WesternPort Bay and fumed: They were not made of money.

He checked his watch: shed been inthe shower for four minutes. He ran.

Ludmilla was towelling herself, skinbeaten pink by the water, slight but unmistakeable rolls of flesh dimpling hereand there as she flexed and twisted. She was letting herself go. He scooped thescales out from under the bed, carried them through to the bathroom and snappedhis fingers: On you get.

She swallowed, draped her towel overthe heating rail, and stepped onto the scales. Just over 60 kilos. Two weeksago shed been 59.

Wishart burned inside, slow, deepand consuming. Presently his voice came, a low, dangerous rasp: Youve put onweight again. I dont like it.

She was like a rabbit in aspotlight, still, silent and waiting for the bullet.

Have you been having businesslunches?

She shook her head mutely.

Youre getting fat.

She found her voice: Its just thetime of the month.

He said, At lunchtime on Friday Icalled you repeatedly. No answer.

Ade, for goodness sake, I was inPenzance Beach, meeting with the residents association.

He scowled at her. The PenzanceBeach residents association was a bunch of do-gooding retirees intent onpreserving an old house. Your car, or a work car?

Work car.

Good.

They breakfasted together; they dideverything together, at his insistence. She drove to work and he walked throughto the studio and arranged and rearranged his architectural pens, rulers anddrafting paper.

* * * *

Meanwhilein an old farmhouse along a dirt road a few kiLornetres inland of Waterloo, HalChallis was saying, Uh oh.

What?

A flaw.

The detective inspector was proppedup on one elbow, playing with his sergeants hair, which was spread over thepillow mostly, apart from the stray tendrils pasted to her damp neck, templesand breasts.

I find that most unlikely, shetold him.

Ellen Destry was on her back, herslender limbs splayed, contentedly. Challis continued to fiddle at her hairwith his free hand but his gaze was restless, taking in her eyes, lips andlolling breasts. She looked drowsy, but not quite complete. She hadnt finishedwith him yet, and that was fine by him. He freed his hand from the tangles andran the palm along her flank, across and over her stomach, down to where shestirred, moist against his fingers.

What flaw? she said unsteadily.

Split ends.

Not in this hair, buster, shesaid, punching him.

He rolled onto his back, pulling herwith him, and as he took one of her nipples between his lips the phone rang.She said Leave it fiercely, but of course he couldnt, and Ellen knew that.Because he was pinned beneath her, it was she who snatched up the receiver. Destry,she said, in her clipped, sergeants voice.

Challis lay still, watching andlistening. Hes right here, she said, rolling off and handing him the phone.

Challis, he said.

It was the duty sergeant, reportinga serious assault outside the Villanova Gardens on Trevally Street in Waterloo.That apartment block opposite the yacht club, sir.

I know it.

Victims in a coma, the dutysergeant went on. Name of Lachlan Roe.

Mugging? Aggravated burglary?

Dont know, sir. Uniforms took theinitial call. The nextdoor neighbour stepped outside to fetch her newspaper andsaw Mr Roe lying on his front lawn in a pool of blood.

Anyone from CIU there?

Sutton and Murphy.

Scobie Sutton and Pam Murphy weredetective constables on Challiss team. Crime scene officers? Ambulance?

The techs are on their way; theambulance has been and gone.

Challis, wondering why hed beencalled, rolled his eyes at Ellen, who grinned and waggled her breasts. When hereached out a hand she ducked away, rose from the bed and padded naked to thewindow. He watched appreciatively. Cute ass, he drawled, covering thereceiver with his hand.

She did a little shimmy and openedthe curtains. The morning sun lit her, and the dust motes eddied, and the worldoutside the window was vibrant: the chlorophyll, the spring flowers, theparrots chasing and bobbing.

Challis returned to the phone. Soits all under control.

There was a pause. Finally the dutysergeant said, It could get delicate. That meant one thing to Challis: thevictim was well known or had connections, and the result would be a headache tothe investigating officers. In what way?

The victims the chaplain atLandseer.

The Landseer School, a boarding andday school on the other side of the Peninsula. Not quite as old as GeelongGrammar, Scotch College or PLC but just as costly and prestigious. Some wealthyand powerful people sent their kids there, and Challis could picture the mediaattention. He glanced at his bedside clock: 6:53. On my way, he said.

He replaced the handset and glancedagain at Ellen, who remained framed in the window. Struck by the particularconfiguration of her waist and spine he crossed to her, pressed himself againsther bare backside.

Next page