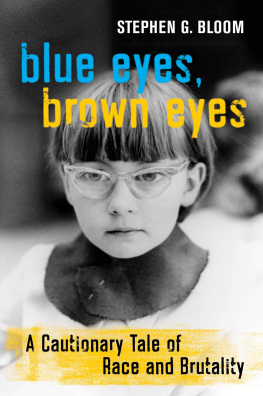

AUTHOR S NOTE: THE SCAB

It started with a phone call.

Is this Stephen Bloom? an emphatic voice asked out of the blue one spring morning seventeen years ago.

Without waiting for a response, the caller sprinted ahead. Well, this is Jane Elliott and I want to talk to you!

I had never spoken with or met Elliott before and I had no idea why shed be calling me. She seemed insistent and determined. The only thing I knew about Elliott was a provocative classroom experiment credited to her.

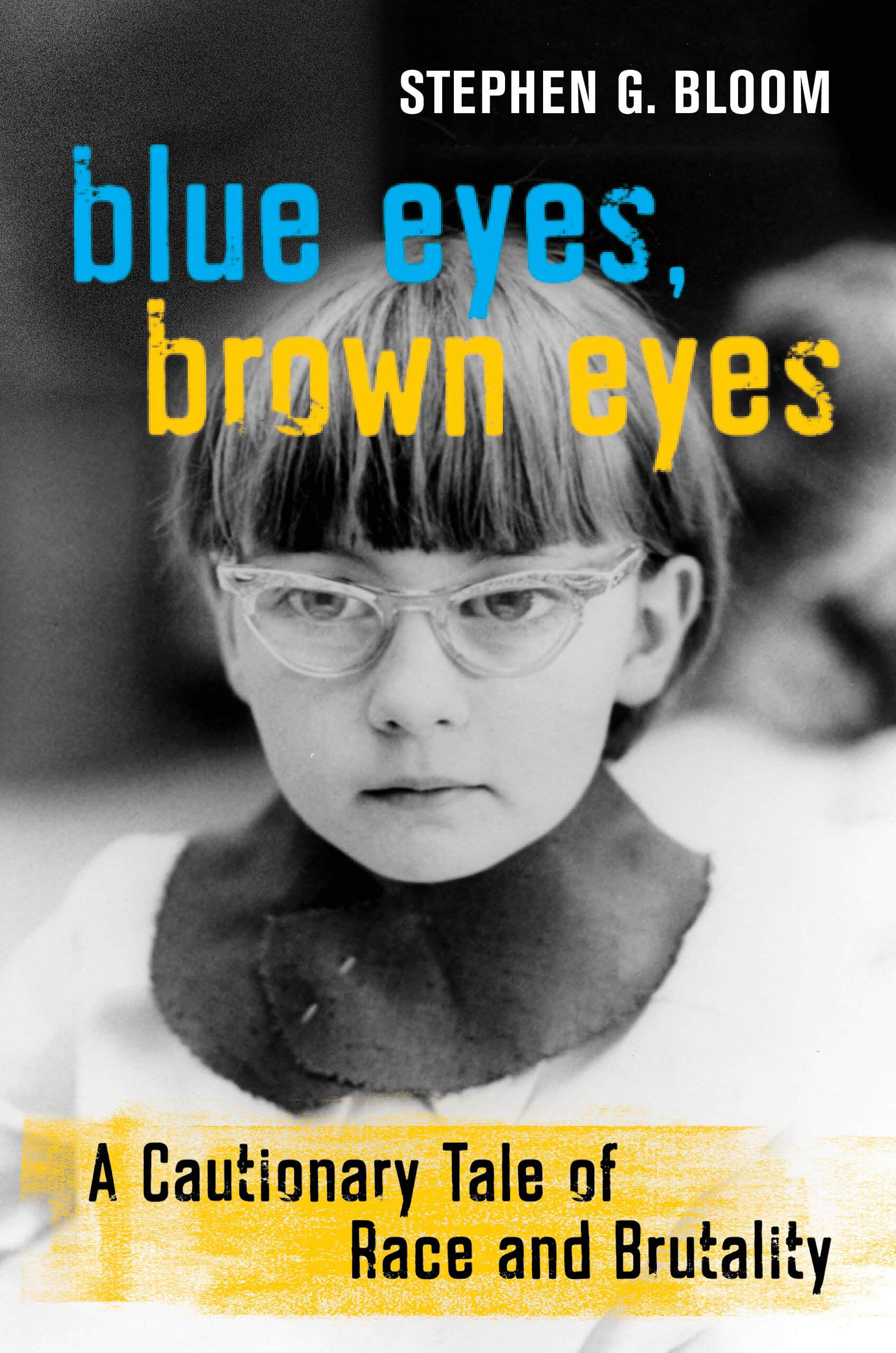

For a decade, Elliott, a teacher in a small, rural Iowa town, had separated her third-grade students, for two days, into two groupsthose with blue eyes and those with brown eyes. On the first day, she told the blue-eyed children that they were genetically inferior to the brown-eyed children. She instructed the blue-eyed kids that they wouldnt be permitted to play on the junglegym or swings. Theyd have to use paper cups if they wanted to drink from the water fountain. They wouldnt be allowed second lunch helpings. The next day, Elliott switched the students roles. The brown-eyed kids would now be considered inferior. The experiment was Elliotts way of showing eight- and nine-year-old white children what it was like to be Black in America. Starting in the mid-1980s and for the next thirty-five years, Elliott would increase the experiments voltage by trying it out on adults in thousands of workshops worldwide.

I asked Elliott why she had called me, and without hesitation, she responded, Because I want you to write a book about me.

At the time, a decade in Iowa had taught me that Iowans generally follow protocol, spoken and unspoken. Many Iowans are reserved and deferential, especially those from the rural part of the state (which is pretty much all of Iowa). Blustery or brazen isnt part of most Iowans DNA.

I was alternately put off and intrigued by Elliotts entreaty. I got the sense that she had set out to find a kindred spirit, perhaps someone who might crack open for her the world of publishing. You cant be conferred global-icon status until you write a book about yourselfor better, until someone writes a book about you.

Elliotts moxie piqued my curiosity, and as soon as I got off the phone, I set out to learn more.

Years before the Black Lives Matter movement or the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in the summer of 2020, Elliott, a white woman from out-of-the-way Iowa, had transformed herself into an international authority on all issues of racism and bias. An award-winning network TV documentary had aired about her, followed by a starring role at a headline-sparking White House conference on education. By 1984, Elliott had left her public school teachers job in Riceville, Iowa (population: 806), sixteen miles from the Wisconsin state line, and had taken the blue-eyes, brown-eyes experiment on the road. She tried it on tens of thousands of adults, not just in the United States and Canada, but also in Europe, the Middle East, and Australia. She traveled to conferences and corporate workshops. She took the experiment to prisons, schools, and military bases. She appeared on Oprah five times. Elliott became a standing-room-only speaker at hundreds of colleges and universities. In the process, she had turned herself into Americas mother of diversity training.

Elliott was so successful at what she did that she was granted membership in the historic pantheon of the Wests most revered educators: Plato, Aristotle, Horace Mann, Booker T. Washington, John Dewey, Maria Montessori, Jean Piaget, and Paulo Freire. In 2004, the American publishing giant, McGraw Hill, created a multipanel poster suitable for classroom display that included Elliott along with the other venerated thinkers and teachers.

In Psychology and Life, a one-and-a-half-inch-thick standard textbook that hundreds of thousands of undergraduates are assigned, Elliotts experiment would be praised as one of the most effective demonstrations of how easily prejudiced attitudes may be formed, and how arbitrary and illogical they can be. The textbooks author, Stanford professor Philip G. Zimbardo, described Elliotts classroom activity as a remarkable experiment, more compelling than many done by professional psychologists.

That Zimbardo had been so struck with Elliott made sense. In 1971, when Elliott was pitting blue-eyed students against their brown-eyed Like Elliott, Zimbardo had become an expert when it came to pushing and pulling levers to reveal humanitys nastiest urges.

In nearly every announcement of her appearances on the lecture circuit, Elliott would tout an endorsement from famed child psychiatrist Robert Coles, a Harvard professor, MacArthur Foundation Award recipient, US Medal of Freedom honoree, and Pulitzer Prize winner. Coless heralded commendationcalling the experiment the greatest thing to come out of American education in a hundred yearscarried certainty and gravitas. It said Elliott was the real thing.

All of the above drew me in, and a week after that first phone call, I found myself driving the one-hundred-and-fifty miles from Iowa City to Mitchell County to meet Elliott. On a cloudless day set against a robins-egg blue sky, she ushered me onto her porch and offered me iced tea in a Ball mason jar while patting the well-worn cushion of a bamboo chair.

I started out all wrong by calling the famous classroom lesson an experiment.

It never was an experiment ! Elliott scolded me, an index finger shooting within inches of my face. I didnt experiment on children! I was their teacher! I was giving a child an experience for the purpose of changing their brain and that is exactly what it does every time I do it. It was an exercise !