This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1961 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

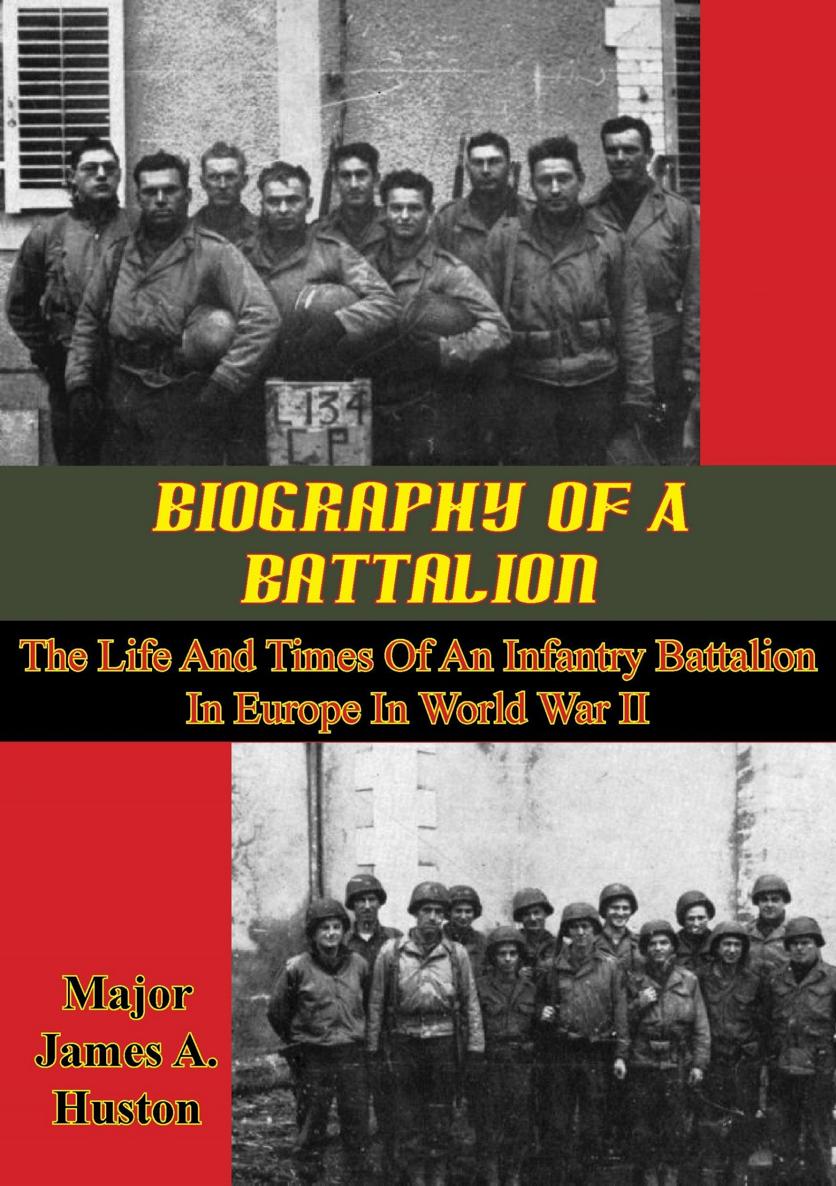

BIOGRAPHY OF A BATTALION: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF AN INFANTRY BATTALION IN EUROPE IN WORLD WAR II

BY

JAMES A. HUSTON

Assistant Professor of History, Purdue University

PREFACE

Early in World War II steps were taken to insure an adequate historical coverage for the events and implications of this great conflict.

At a meeting in August, 1943, the committee [on Records of War Administration] considered the broader aspects of the history of World War II and agreed upon six over-all objectives. The committee took no responsibility for the wide coverage indicated by the following objectives, but did call attention to certain principles:

1. All of the major Federal Agencies should gather data relating to their development and their most significant activities during the war period in order to create a central historical file.

2. There should be several non-official and popular accounts of World War II written from different standpoints, showing the military operations of the war, the civilian administration of the war, and the diplomatic phases of the war.

3. There should be a series of scholarly monographs analyzing the effect of the war on important phases of our social and economic life.

4. Studies should be made on a selected list of topics that are the concern of no one government or private organization.

5. State historical groups should prepare accounts of state activities in World War I.

6. Leading American industrial firms should have histories written recounting their war work.

The objectives outlined above conform closely to those approved in the business meeting of the American Historical Association on December 30, 1942. {1}

The War Departments American Forces in Action series provides some excellent studies of action in specific operations, and its projected 99 volume history promises results in quality to equal its magnitude in quantity. Nevertheless, an adequate treatment should include accounts of infantry units carried throughout the war. A large number of infantry divisions already have published histories, and these do have a definite value to anyone seeking an understanding of the military phase of the war; however, these accounts frequently display a temptation to dwell too much on self-glorification at the expense of more complete accuracy and perspective.

But the story of the typical infantry battalion is one which deserves to be told. Battalion, because the battalion is the largest unit whose commander habitually follows the troops on the ground. It is the smallest unit whose commander has a staff to assist him in his dutiesa fact which lends a measure of continuity to the battalion in spite of the rapid turnover of its personnel. It is the level where the interplay of strategy and large unit tactics with the tactics of the small unit can be seen most clearly.

If any infantry battalion can be called typical, perhaps the 3rd Battalion, 134th Infantry (35th Division) has as good a claim to that description as any. The story of this battalion includes participation in the Normandy campaign and the capture of St. L under General Omar Bradleys First Army; the dash across France, the advance through Lorraine, and then the relief of Bastogne in the Ardennes Bulge under General George S. Patton Jr.s Third Army; the drive from the Roer to the Rhine, the fighting in the Ruhr valley, and the race to the Elbe, little more than fifty miles from Berlin, under Lieutenant General William H. Simpsons Ninth Army. The story of the typical battalion must include each of the major campaigns, for in some ways they were so different as to seem almost different wars.

Infantry units seemed to have a great deal in commonin battle experiences as well as in the common background of training. Each seemed to have its St. L, its Bloody Sunday, its Blue Monday.

My own position to relate this story is, perhaps, unique. Aside from the motor officer and the supply officer, I was the only officer in the Battalion to survive its whole period of combat. After completing the Basic course, as a reserve officer, at the Infantry School, Fort Benning, I joined the regiment in California as a rifle platoon leader in May, 1942. After subsequent assignments as battalion anti-tank platoon leader, rifle company executive officer, and rifle company commander, I joined the Third Battalion as temporary S-3 (operations officer) at the termination of maneuvers in Tennessee in January, 1944. On the return of the regular operations officer (Captain Merle R. Carroll) from another course at Fort Benning, I remained as Battalion intelligence officer (S-2).

It was in this position that I entered combat with the Battalion in Normandy in July, 1944. As S-2 I was concerned primarily with information of the enemyreconnaissance, prisoners, map distribution. Then early in September the Battalion operations officer was wounded and I succeeded to that assignment. Now it was my duty to accompany the Battalion commander wherever he wentto regimental meetings to make notes on the regimental orders, to conferences with other commanders, to the companies on visits or inspections, to the observation posts, behind the advancing companies during attacks. The days work included preparation of field orders, transmission of orders and directions to the company commanders, coordination with supporting units and friendly units on the flanks, preparation of training schedules and supervision of training.

In the preparation of this history every effort has been made to corroborate my statements by reference to reliable documents or the observations of others. However, statements which rest on no other authority depend upon my personal observation. My own experience, then, has served in a positive way to supplement other information, and in a negative way to afford a critical evaluation of the available documents.