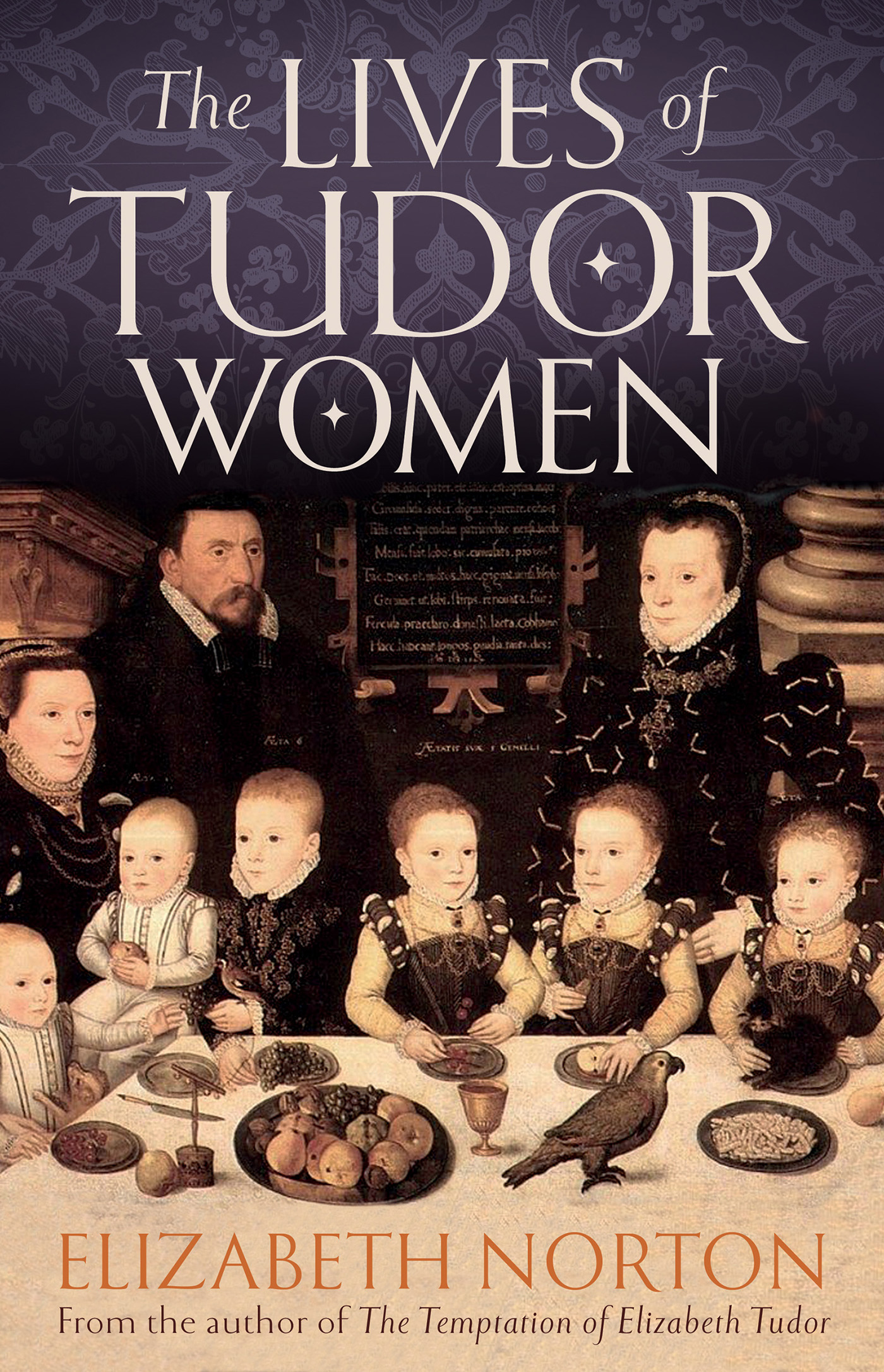

THE LIVES OF TUDOR WOMEN

Elizabeth Norton

www.headofzeus.com

The turbulent Tudor age never fails to capture the imagination. But what was it actually like to be a woman during this period?

This was a time when death in infancy or during childbirth was rife; when marriage was usually a legal contract, not a matter for love; and the education of women was minimal at best. Yet the Tudor century was also dominated by powerful and characterful women in a way that no era had been before.

Elizabeth Norton explores the seven ages of the Tudor woman, from childhood to old age, through the diverging examples of women such as Elizabeth Tudor, Henry VIIIs sister who died in infancy; Cecily Burbage, Elizabeths wet nurse; Rose Hickman, merchants wife, religious activist and exile; Elizabeth Boleyn, mother of a controversial queen; and Elizabeth Barton, a peasant girl who would be lauded as a prophetess. Their stories are interwoven with studies of topics ranging from Tudor toys to contraception to witchcraft, painting a portrait of the lives of queens and serving maids, nuns and harlots, widows and chaperones.

For David, Dominic and Barnaby

Contents

Elizabeth of York and the first Elizabeth Tudor

Cecily Burbage, Elizabeth of York and the infant Elizabeth Tudor

Elizabeth Tudors brief life

The Countess of Surreys girls, Jane Dormer, Lady Bryan and Margaret Beaufort

Elizabeth Barton, maidservant

Cecily Burbage and Elizabeth Boleyn

Katherine Fenkyll, wife and business partner

Katherine Fenkyll, independent businesswoman

Elizabeth Barton, the Holy Maid of Kent

Catherine of Aragon, the Boleyns and Elizabeth Barton

Elizabeth Barton and Anne Boleyn

Elizabeth Barton and Anne Boleyn

Margaret Cheyne, Lady Bulmer

Joan Bocher, Anne Askew and Catherine Parr

Joan Bocher, Princess Mary and Jane Grey

Queen Mary, Rose Hickman, the Marian martyrs, Margaret Clitherow and the new Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth and Rose Hickman

Queen Elizabeth in her sixties, and the witches of England

Jane Dormer, Gloriana and the poor women of England

This is a biography. It looks at the life of a woman, who was born in 1485 and died in 1603. She was a princess, a queen, a noblewoman, a merchants wife, a servant, a rebel, a Protestant and a Catholic. She was wealthy, she was poor. She married once, twice, thrice and not at all. She died in childbirth, she died on a burning pyre, she died at home in her bed. She spent most of her life in the house, and she left home when young and did remarkable things. She changed England and was celebrated forever, and she was forgotten, a mere footnote. She was all these things and more. She was Tudor woman, and this is her story.

*

The ruling Tudor dynasty was bookended by two princesses named Elizabeth Tudor the one born in 1492, whose brief years passed into obscurity, and the other who dominated her era and brought the dynasty to its close with her death in old age, in 1603. Their lives are the full-stops between which countless lives of other Tudor women were lived.

This book is a collective biography, sampling, to different extents, the diverse lives enjoyed or endured by women living in Tudor England, and together constituting a multifaceted impression of female humanity of the period: a Tudor Everywoman. It is a concept contemporaries would have been familiar with after all, it was the early Tudor period that produced the allegorical play The Summoning of Everyman .

To the people of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century England, life could be divided into phases the Seven Ages of Man, articulated most famously by Shakespeare, in As You Like It , as infant, schoolboy, lover, soldier, the justice of the peace, the ageing retiree and, finally, the infirm elder. From the female perspective, those Ages could never apply in quite the same way, in an era when women were largely denied any official, public role; but even where the Ages differ, there are yet analogies.

If, at birth, our Tudor Everywoman was a princess named Elizabeth, and at death a queen named Elizabeth, in between she was among many other people a daughter named Anne Boleyn, a servant girl-turned-prophetess named Elizabeth Barton, a businesswoman named Katherine Fenkyll, a widow named Cecily Burbage, a rebel named Margaret Cheyne, a heretic named Anne Askew, and an expatriate of advanced years named Jane Dormer. These particular names have lived on in the history books, and they provide major nodes in a network whose minor, but no less illustrative, points comprise much of what follows: the poor wool-spinners of East Anglia, the witches of Surrey and the female apprentices of Bristol; the women who taught and those who fostered learning; the women who vowed to remain chaste and the women who made a living from sex; the women who kept their communities morally upstanding and the women who were driven to slander, thievery and murder; the women whose horizons seemed sunlit, and those whose lives ended in despair, in a noose tied by their own hands.

For some, the experience of Tudor womanhood ended very early as it did for the first Elizabeth Tudor and for the unfortunate, illegitimate Mary Cheese: she, like a number of other newborn girls, found no welcome in an unsentimental world. For those that survived infancy, there was the stuff of girlhood and play, a variable education (according to social class and geography), and perhaps some temporary employment or domestic service before marriage and (for many) motherhood. With marriage, employment, in any modern sense of carrying out a paid or public role outside the home, was usually over. But other women remained unmarried, and ran independent businesses as a femme sole or continued in a career. Some ended up on the wrong side of the law, others were entirely law abiding and a few spent a good while inside the law, embroiled in suits and counter-suits.

Women were not isolated from the turbulence around them, as a contested Reformation gathered pace in England, its catalyst being Henry VIIIs desire for a divorce. Some women saw the light or saw their own particular light and in an age where public toleration of diverse opinions over religion or kingship was anathema, there were consequences for women who spoke out. Women could not be soldiers one of Shakespeares middle ages and neither could they, with the unusual exception of two ruling queens, dispense justice by holding any public office. But a surprising number of women were highly political, deliberately or implicitly whether they were motivated by desire for power, devotion to their faith, support for their family, or the myriad of other reasons that could draw them away from the home.

The final two of the Seven Ages saw the descent into old age for women who had escaped the hazards of childbirth and the risks of disease, accident or execution. For those who did get that far, the final years presented new challenges and great contrasts. Alice Taylor, an aged and impotent wench of Ipswich, spent her last years very differently to Elizabeth I in the 1590s, who by this time had reached her summit as Gloriana. But as both of them looked around, they would have seen more women of their own age than men. With their greater longevity, many more women than men saw out all of the Seven Ages.

It is perhaps fitting, therefore, that the Tudor era itself reached the end of its Seventh Age in the last breaths of one of its most adept, extraordinary women.