Wounded soldiers arriving by train at the Valley Forge Military Hospital in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, May, 1943

Copyright 2020 by Shelley Fraser Mickle

Photograph credits listed on

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Charlesbridge and colophon are registered trademarks of Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc.

At the time of publication, all URLs printed in this book were accurate and active. Charlesbridge and the author are not responsible for the content or accessibility of any website.

An Imagine Book

Published by Charlesbridge

85 Main Street

Watertown, MA 02472

(617) 926-0329

www.imaginebooks.net

Ebook design adapted from printed book designed by Ronaldo Alves

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mickle, Shelley Fraser, author.

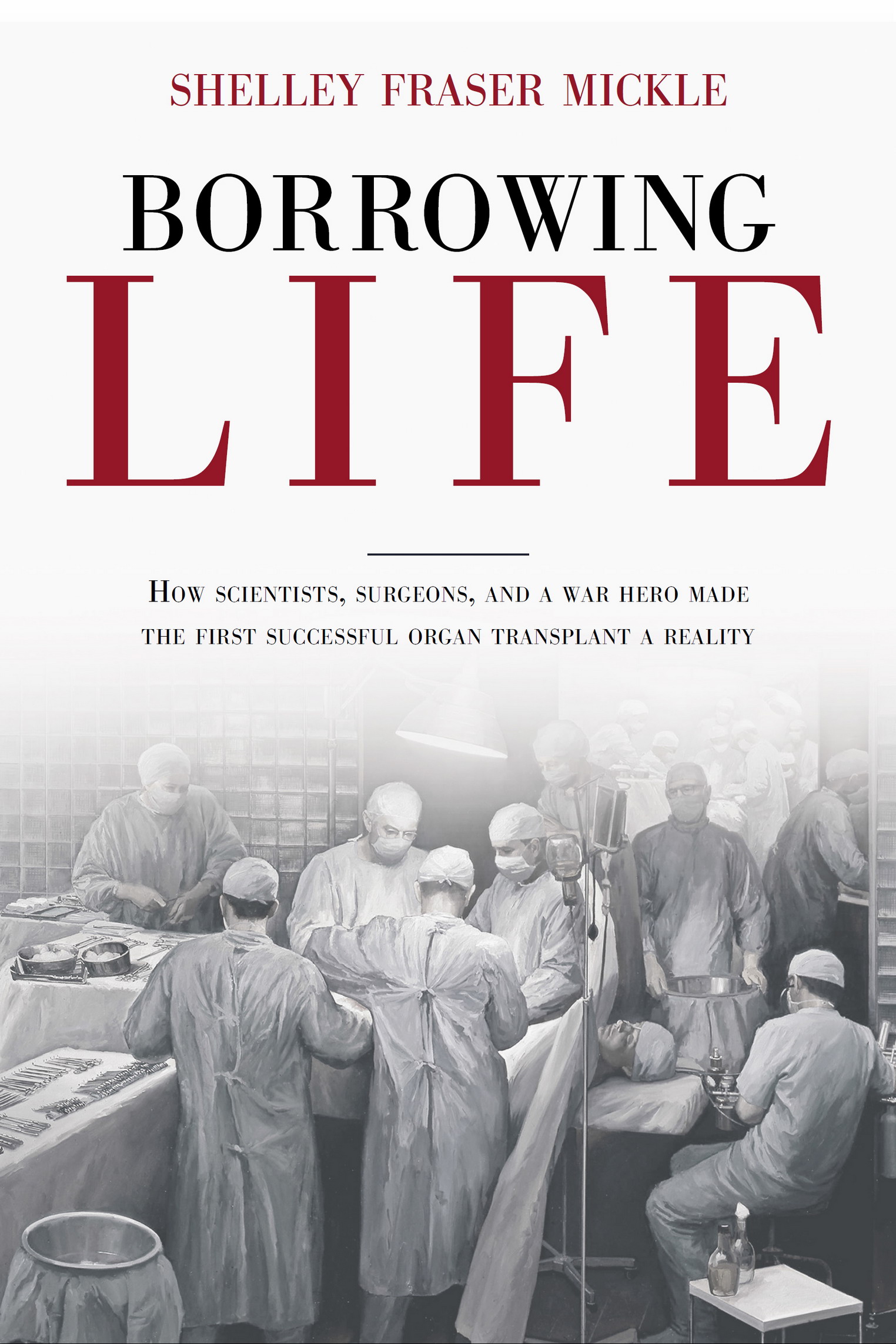

Title: Borrowing life : How scientists, surgeons, and a war hero made the first successful organ transplant a reality/ by Shelley Fraser Mickle.

Description: Watertown, MA : Charlesbridge, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019015877 (print) | LCCN 2019019421 (ebook) | ISBN 9781632892294 (ebook) | ISBN 9781623545390 (reinforced for library use)

Subjects: LCSH: KidneysTransplantationBostonHistory. | Transplantation of organs, tissues, etcHistory. | Peter Bent Brigham HospitalHistory.

Classification: LCC RD575 (ebook) | LCC RD575 .M53 2020 (print) | DDC 617.4/610592dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019015877

Ebook ISBN9781632892294

v5.4

a

For Parker

Discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought.

Albert Szent-Gyrgyi

Illnesshas its inspirations.

Albert Camus

Contents

A Note to Readers

T HIS STORY BEGINS during World War II, six months after D-Day, when the worst fighting was still ahead. The Battle of the Bulge had just started; the crossing of the Rhine River was three months away. To tell it well, I must begin at an unexpected place. I say unexpected because when two young men came together that January of 1945one a burned pilot, the other a surgeon determined to save himthey had no idea they were about to take the first step in making one of the most valuable contributions to mankind in the twentieth century.

While this story is mostly about what scientists and surgeons can achievegiven curiosity, a passion for science, a large dollop of compassion, and a little luckits a whole lot about how a science fiction-like dream pushed two American surgeons and a British scientist to scale the wall of what was deemed to be impossible. Over a decade they pioneered the giving and taking of organs that one of the surgeons called spare-parts surgery, or borrowing life, which in no way belittled the ultimate gift of retrieving life for one so close to losing it.

In the late 1960s I knew two of the three. The American ones. I was too young and dumb to know I was walking among giants. The British one I know now by the energy of his words. And those of his wife, whose touching memoir gives us an idea of what it was like to love Peter Medawar, a scientist so important to the understanding of the universe of the immune system that his colleagues compared him to Galileo. Yes, Jean Medawar, like the wives of all these men, is unequivocally part of this narrative. As is Miriam Woods, who gives clear meaning to the words in sickness and in health as she devotedly rushed to be with her husband after a horrendous World War II plane crash. So here are four gripping love stories. In fact, before anyone answers that all-powerful question, Will you marry me?, they should ask: Will you love me like Miriam loved Charles, like Joe loved Bobby, like Franny loved Laurie, like Jean loved Peter?

Surgeon Joe Murray performed the first successful kidney transplant in December 1954 in a five-and-a-half-hour surgeryso monumental that it is immortalized in an oil painting hanging in the Countway Library in Boston next to the painting of the first surgery performed with ether. It is that important. Joe himself is a study in star stuff. At birth he was given giftsthose of both heredity and tradition. His family practiced irrepressible cheer as a matter of habit. His questing intelligence, unwavering buoyancy, uncommon dexterity, and an extraordinary compassion for those who sufferedespecially for those who had to walk out into the world with a horrendous facial deformity, particularly childrenseem almost superhuman. He said in his Nobel Prize lecture in 1990 that his life as a surgeon-scientist gave him the rewarding experience of witnessing human nature in the raw: fear, despair, courage, understanding, hope, resignation, heroism. Indeed, his part in this story allows us to get our minds around the slippery concept of hopeand how not to lose it. Joe was not just one among many in the greatest generation, he was the kind of man who evokes prayers of please God, make more like him.

Francis (Franny) Moore had the mettle of old New England running in his veins, the kind of grit that could make a man want to found a nation. Extraordinarily gifted as a surgeon-scientist, he was also extraordinarily gifted as a leader. And he had vision. He could foresee the promise of organ transplantation as a viable treatment for devastating injury and disease, thus opening the gates for the monumental first organ transplant in 1954. But that was not all. His understanding of how the body reacts to surgery still affects every patient who comes through a hospital door.

It was said that when Franny entered a room, it was like being in the midst of a full-scale orchestra performing a roof-raising symphony. He was that commanding. Paternal, wanting to take over and fix everything for everyone, he was loath to waste a minute, as if time and suffering were his enemies on the battlefield of sickness. Even his secretary said of him that Dr. Moore lives life on a different plane. In short, he was like many esteemed people in history: he didnt have to do what he did. Born wealthy and privileged, he was driven by that elusive trait that we all wish for ourselves and for our children, and yet cant quite name. Simply put: Get off your duff and pursue excellence for its own sake. He would become the youngest surgeon to ever be named the Moseley Professor of Surgery at Harvard.

Peter Brian Medawarhow can we even grasp the whole of who he was? After witnessing a Spitfire crash near his home in Oxford, England, during the Battle of Britain, he became so haunted by the suffering of the burned pilot that he focused his brilliant mind on unveiling the secrets of the bodys immune system to supply long-lasting skin grafts. His learning to bamboozle the bodys system of defense to manipulate rejection established a new field of science, immunogenetics. In fact, Peter would make such a monumental contribution to the understanding of human biology that he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine when he was only forty-five.

So here is this story: blending the horrors of war with the boldness of youth and the clenched-teeth defiance to not relinquish hope, it begins in December 1944 and will continue to be told well beyond today. Because borrowing life to extend the lives of those suffering from organ failure has enabled scientists of the present and future to apply the immune systems exquisite power to treating cancer and other ravaging diseases.