Preface

The interest in aesthetics in anthropology is longstanding, although attempts to develop its study have been sporadic. For perhaps two reasons, anthropologists have been reluctant to examine this area. First, definition of the subject matter has proved problematic, even within the confines of Western culture. Philosophers have argued for centuries over what constitutes an aesthetic experience, an aesthetic form, and so on. The attempt to find terms that have some cross-cultural validity seems, as a result, hopeless. Second, responses to aesthetic forms are personal, interior states that are notoriously difficult to fathom by ethnographic means.

Anthropologists have resolved these problems by sidestepping them. Many fieldworkers have concentrated on a single genre or artisan and by so doing largely avoided the problem of definition. Hopi dance, pygmy music, Yoruba sculpture, and other such expressions fit our intuitive (Western) sense of what an aesthetic form is and so can be studied first and placed in an analytic framework afterward. Furthermore, many theorists have found it satisfying to explore and codify the formal features of aesthetic formspreference for straight versus curved lines in painting, smooth versus staccato rhythms in music, horizontal versus vertical extension in dance. These preferences they could correlate with the formal features of other parts of the social system without making reference to the subjective states of the people involved.

Single-genre and formal studies currently dominate aesthetic anthropology and severely limit its enormous potential. This is not to say that such investigations have been wasted, for they have produced many richly complex analyses. But there is so much more that can be achieved. My aim in this book is to set a new agenda for aesthetic anthropology by broadening the field to encompass the total aesthetic experience of a people and to venture beyond the formal and external to the affective interior.

The most obvious reason for examining the total aesthetic experience of a community is that aesthetic forms exist in an aesthetic context. The music of a Southern Baptist church service, as I will show, is performed in a building whose furnishings and architecture are of aesthetic significance. The music is only one part of a larger performance whole that includes drama, poetry, and oratory, and these forms in turn have wider contexts. Church architecture may be like house architecture in certain respects and unlike it in others; music making may be frowned upon outside the church. To study Baptist church music in its social context, the commonest starting point for single-genre and formal investigations, is therefore to miss a vital step. First the music must be situated in its aesthetic context.

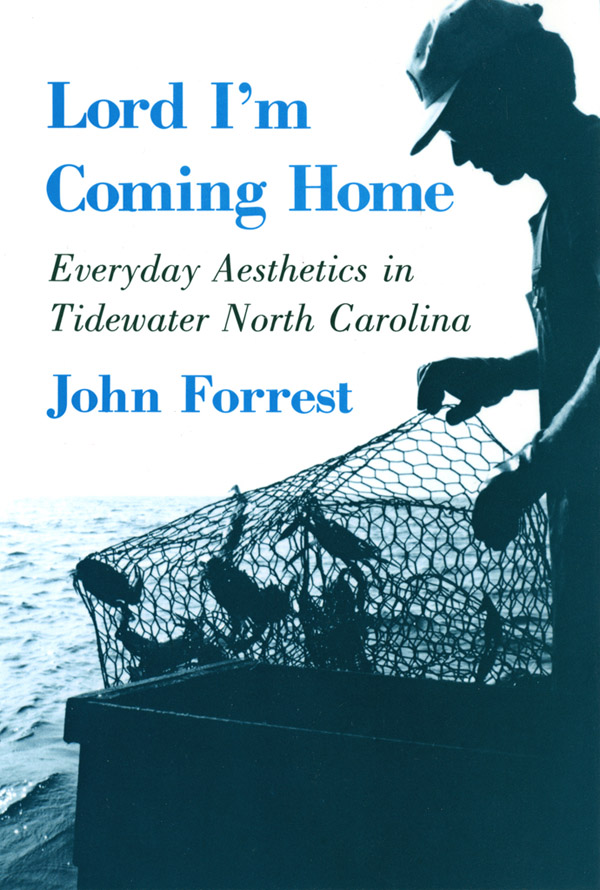

The natural result of investigating the entire aesthetic realm is a reduction in interest in particular forms. To tackle every aesthetic form the way an ethnomusicologist, say, would study the music might complicate matters so much as to obscure the general picture of aesthetics in action. What I have striven to present is a greater feeling for the aesthetic experience as an everyday experience and not some rarefied and pure behavior reserved to an artistic elite. I hope to show what a fisherman sees when he peers at sunset across still water, what he tastes when he eats greasy greens with vinegar and onions for supper, and how such sights and tastes complement one another in a coherent aesthetic sensibility.

To be a participant in, as well as an observer of, local aesthetic experiences, the anthropologist needs to employ special methods of ethnographic reportage. With the exception of Chapters 2 and 3, which deal in detail with theoretical and methodological issues, this book mirrors my own experience as an ethnographer. It begins with a fictionalized account of one fishermans day in Tidewater, the North Carolina fishing community studied. You, the reader, get to sit in the boat with Charlie, as I did, to follow his routine, to see how he makes decisions. From the outset you are immersed in the myriad social details that the ethnographer must somehow record and make sense of. From this vantage point you can sift out the aesthetic experiences, and, most important, you can begin to see them not as quantifiable social facts but as live, affecting, subjectively real entities. This chapter, then, is designed to provide what I so often miss in ethnographies, a feel for the general course of everyday life as it is lived by the people under study before every behavior is torn apart, microanalyzed, and categorized. Even though some artifice is involved in creating a composite, fictionalized picture, I hope to suggest here that daily life can be presented reasonably directly and that the aesthetic (and other) decisions people make can be seen in an operational context.

Once I had got my bearings in the community, I began documenting and sorting data into locally meaningful categories. Hence four chapters detail the aesthetic forms in four realms of life in Tidewater: home, work, church, and leisure. The material here is, for the most part, descriptive of what I saw, with only occasional attempts at analysis. I believe it is important to understand the many and varied aesthetic forms in their own terms before one dissects them. What analysis appears in these four chapters is of a preliminary nature, and I make no attempt to incorporate comparative materials. My goal is to see aesthetic forms in their local context.

In the years that followed my fieldwork I digested what I had recorded and worked it into a pattern that I am now satisfied is coherent and does justice to the community. This analysis concludes the ethnography and leads to some general theoretical speculations that continue to guide me in new fieldwork projects. The whole, therefore, has a circular (or perhaps helical) quality, starting with all of the aesthetic forms integrated, followed by the teasing out of individual elements, and leading to a new integration, this second time analytic and abstract where the first is personal and direct.

This work would not have seen the light of day were it not for the patient but insistent encouragement of my mentor and friend James Peacock. He was instrumental in my receiving grants from the Research Foundation and the Anthropology Department of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to conduct the fieldwork, which support I also gratefully acknowledge. He has read and commented on every draft of the manuscript with great care. At times when I have set this project aside in favor of others, he has gently prodded me to return to it and provided me with opportunities to present segments of my research to interested scholars. In subtle and straightforward ways he has been a generous colleague and guide.

Likewise, Deborah Blincoe has given professional and technical assistance to the project at all stages. She has worked with the manuscript at every point in its development and used her deep understanding of the subject matter to create the illustrations. In so many cases these drawings epitomize the aesthetic forms of Tidewater in ways that not only enhance the text but express what it is often impossible to convey by words alone. She also devoted great energy to specific points of analysis, particularly of the tales, providing insights from her knowledge of the relevant literature. Finally, she added significantly to the style of the whole through patient and sensitive readings of the text.