THE LANGUAGE OF THE TAJ MAHAL

Islamic South Asia Series

Series Editor Ruby Lal, Emory University

Advisory Board

Iftikhar Dadi, Cornell University

Stephen F. Dale, Ohio State University

Rukhsana David, Kinnaird College for Women

Michael Fisher, Oberlin College

Marcus Fraser, Fitzwilliam Museum

Ebba Koch, University of Vienna

David Lewis, London School of Economics

Francis Robinson, Royal Holloway, University of London

Ron Sela, Indiana University Bloomington

Willem van Schendel, University of Amsterdam

Titles

Sexual and Gender Diversity in the Muslim World: History, Law and Vernacular Knowledge, Vanja Hamzic

The Architecture of a Deccan Sultanate: Courtly Practice and Royal Authority in Late Medieval India, Pushkar Sohoni

Sufi Shrines and the Pakistani State: The End of Religious Pluralism, Umber Bin Ibad

The Hindu Sufis of South Asia: Partition, Shrine Culture and the Sindhis in India, Michel Boivin

Islamic Sermons and Public Piety in Bangladesh: The Poetics of Popular Preaching, Max Stille

The Mosques of Colonial South Asia: A Social and Legal History of Muslim Worship, Sana Haroon

The Language of the Taj Mahal: Islam, Prayer and the Religion of Shah Jahan, Michael D. Calabria

THE LANGUAGE OF THE TAJ MAHAL

Islam, Prayer, and the Religion of Shah Jahan

Michael D. Calabria

O God, if you do not shepherd me, I am lost;

If you shepherd me, then I cannot go astray.

O God, if I make a mistake out of ignorance,

I implore you for forgiveness even before it has vexed anyone.

- from The Late Shah Jahan Album

Plates

Mumtaz Mahal. From the Dara Shukoh Album, attributed to Bishn Das, 16313. British Library Board, London (BL Add.Or.3129, f. 34)

Prince Khurram (Shah Jahan) at age twenty-five. Nadir al-Zaman, c. 1615. Victoria and Albert Museum. (IM. 141925)

Shah Jahan, c. 1630. Hashim, active 1598c.1650. 5.4 x 3.7 cm. Cleveland Museum of Art, gift of J.H. Wade 1920.1969. Reproduced by kind permission of the Cleveland Museum of Art

The mausoleum of the Taj Mahal. Authors Photograph

Moti Masjid, Agra Fort. 164753. Authors Photograph with permission of the Archaeological Survey of India, Agra Circle

Jami Masjid, Shahjahanabad, Delhi. 16506. Authors photograph

Shah Jahan Receives a Persian Ambassador, c. 1640; attributed to Payag. Courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford (MS. Ouseley Add. 173. F. 13v). Detail

View of the Taj Mahal complex to the north, with the forecourt (jilaukhana), the Great Gate, Paradise Garden, Mausoleum, mosque and guest house (mihman khana) to the left and right of the mausoleum respectively. Courtesy iStock

Taj Mahal mausoleum, north faade. Srah Y Sn 36.45 ff

Taj Mahal mausoleum, central chamber, with inscriptions. Courtesy iStock

Taj Mahal Mosque, mihrab. Authors collection

Taj Mahal. Great Gate, north faade. The beginning of surah al-u. Authors collection

Taj Mahal, Great Gate, north faade. The end of surah al-Tn and colophon: Finished with His Help, the Most High, 1057 (1647/48 CE). Authors collection

Mullah Shah and Mian Mir on a Terrace, c. 1630s. Opaque watercolor on paper. Yale University Art Gallery. The Vera M. and John D. MacDonald, B.A. 1927, Collection, Gift of Mrs. John D. MacDonald. 2001.138.59

Shah Jahan holding a jeweled sarpesh, c. 1655. 23.4 x 14 cm. Bodleian Library (MS. Douce Or.a.3, f. 1r)

The Shah Burj at Agra Fort wherever Shah Jahan lived under house arrest from June 1658 until his death in January 1666. The Taj Mahal can be seen in the distance. Authors photograph

Figures

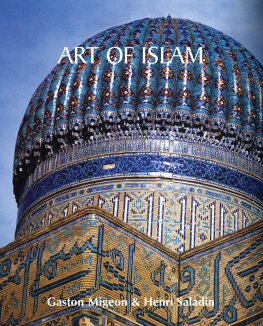

In 2009, I made my first trip to India. Fr. Xavier Seubert, OFM, then director of the Art History program at St. Bonaventure University, had asked me to develop an undergraduate course on Islamic Art and Architecture. Although I knew well the Islamic artistic and architectural legacy of the Maghreb and Middle East, I had yet very little knowledge of the Islamic heritage of South Asia. Thus, after obtaining a grant from the Keenan-Martine Foundation at St. Bonaventure University, I set out for New Delhi from Cairo where I had been teaching for the summer. Although I visited and studied the magnificent mosques and mausolea from the period of the Delhi Sultanates (12061526), it was Indias Mughal monuments that captivated me, especially the iconic Taj Mahal, built by the emperor Shah Jahan as the funerary complex for his beloved wife, Arjumand Banu Begum, known to history as Mumtaz Mahal, the Chosen One of the Palace.

As a professor of Arabic as well as Islamic Studies, I had come to think about the Taj Mahal, not only as a work of architecture, but as text. My preliminary research had already revealed that its structures were inscribed with fourteen complete srahs (chapters) of the Quran, and assorted verses from several other srahsa total of 241 verses (yt), making it the most extensive inscriptional program of any Mughal monument, any Islamic monument in South Asia, and indeed in the entire world. The Quranic texts are rendered into calligraphy of outstanding beauty, and while the texts are therefore highly decorative, they are not merely decoration. Indeed, on my first visit to the Taj Mahal, with the Quranic texts in hand, I began to read the monument which has much to say. Before rushing through the Great Gate (darwaza-i rauza) to see the mausoleum as tourists so often do, I stood and recited srah al-Fajr inscribed on the outer faade of the gate. I was struck by the power and profundity of its message to humanity, a message that seemed as relevant to contemporary India and the world, as it did in Shah Jahans day. Although often overlooked by tourists and scholars alike, these inscriptions did not escape the attention of the Mughal court chronicler Abd al-Hamid Lahori who, on the twelfth anniversary (urs) of the queens death in 1643, wrote a detailed description of the entire complex, including the following:

This current volume is a modest response to Lahoris observations and an attempt to fill a lacuna in the prodigious research that has been done on the architecture of the Taj Mahal, but which has largely overlooked its inscriptions or treated them minimally in a few pages at best. In 1978/9, Wayne Begley published a lengthy article on Amanat Khan, the man responsible for much of the Taj Mahals calligraphy. In that piece, Begley wrote that he was preparing a monograph on the symbolism of the Taj Mahal and its inscriptional program, but he never wrote that book. Instead, he published an article shortly thereafter titled: The Myth of the Taj Mahal and a New Theory of Its Symbolic Meaning,however, do not have to be read per se to have meaning. The inscriptions serve as a visual representation of Gods eternal word revealed to humanity. Their very presence in this form, in the language of their revelation, makes them true, real, and meaningfulfor the living and the dead.

This volume is therefore directed particularly to those who wish to gain a deeper understanding of the Taj Mahal, not only as a work of architecture, but as a monument of faith as expressed in the relationship between religious architecture and revealed text. The biographical and historical content in the introductory and concluding chapters, as well as throughout the commentary, contextualizes the Quranic inscriptions of the Taj Mahal within the life of Shah Jahan in a way that has not been attempted before. The broad outlines of Shah Jahans life have been treated in recent decades in numerous historical surveys, including John Richards volume on the Mughal Empire in