To my sons, Hugo and Leo.

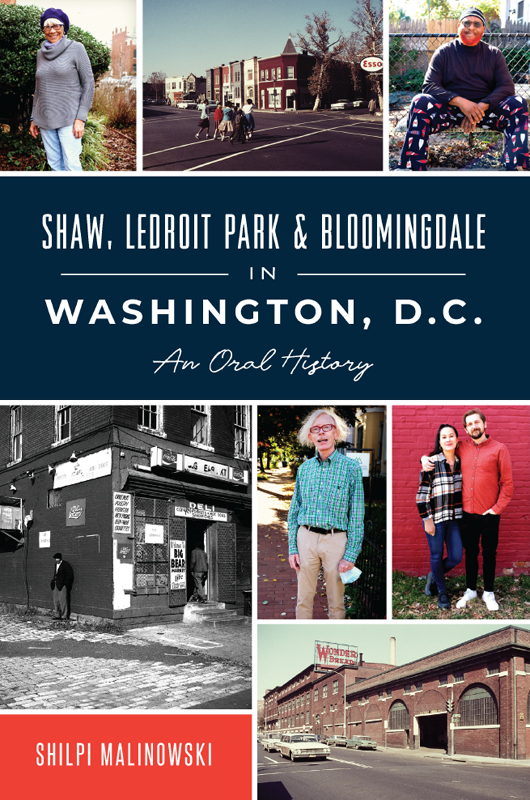

PREFACE

In 2019, I quietly entered living rooms across the most gentrified neighborhood in Washington, D.C., and I listened.

By some measures, the 20001 zip code encompasses the most gentrified neighborhood in the country. The same Victorian-style row house, ubiquitous throughout Shaw and Bloomingdale, that was sold for $8,000 in the 1950s is now on the market for $1.3 million (and the sale prices rise daily). According to a calculation by RENTCaf, a real estate analysis site, the zip code 20001 was the second fastest gentrifying area in the country between 2000 and 2016, judged by the increase in home values, household income level and proportion of residents with higher education.

Countless articles have been written about the area, and I noticed something: the most common narrative simplified the dynamic to two groupsBlack and White, poor and rich, original residents and gentrifiers. White people pushing out Black people.

For the past ten years, Ive been living in this neighborhood and reporting on real estate and development for local publications. I realized that the situation was much more nuanced than that. The diversity of experience, perspective and feeling within both the Black community and the White gentrifier community was getting lost. Some of the first White people who moved in, paying $300,000 for their homes in the early 2000s, lived as racial minorities for years and had no expectation of fancy restaurants or cleaned-up public spaces. They could not be lumped into the same group as the newest gentrifiers, who paid $1.3 million for the same place and expected a sparkling, crime-free neighborhood with a luxurious atmosphere. Black renters who had been displaced when their landlords decided to sell at a profit were nowhere to be found in the neighborhood. Other Black residents who lived through the worst of the drug years were sitting on boards and in community meetings with White residents, planning arts festivals and demanding good grocery stores and neighborhood-serving amenities from developers. Others, who had worked hard to improve their neighborhoods during the crack epidemic, are now being looked at with suspicion by the new White neighbors. But at the same time, I saw interracial friendships blossom between people who had never lived in an integrated neighborhood before.

I knew that White gentrifiers were being blamed for displacing Black residents, and I did notice that numbers showed a shrinking Black population, and a growing White one. But at the same time, the stories I heard from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s were of a drug-addled neighborhood full of vacant houses. The census numbers show a drop in overall population in the 1980s and 1990s and then a rise.

So, just how true was the typical gentrification narrative? What was the full story of living in this integrated neighborhood?

I felt the need to create a more comprehensive and truer portrait of this neighborhood, so I launched this oral history project. I sat in living rooms in the neighborhood row houses and listened as the owners told me about their personal histories. They shared the moments they chose to move here, their first impressions and their observations as the neighborhood went through wave after wave of change. They shared their unfiltered feelings: how safe they felt or didnt feel, how comfortable they were with their neighbors and what they expected from their neighborhood.

My goal was to be comprehensive in choosing interview subjects. Ive arranged the book chronologically, starting with a narrator who was born in the area in the 1940s. From there, others enter the scene as they were either born here or moved in; every decade is populated, and my most recent narrators bought a home in 2020. Together, they describe a staggering change. The subjects of this book have seen this area go from a poor and peaceful neighborhood, to an open-air drug market and to a wealthy and amenity-filled space, and they have seen it go from full, to nearly vacant, to full again. Neighborhood schools were officially segregated, then school integration and White flight left them with de facto segregation, and now, they are integrating.

When Gretchen Wharton came to Shaw in 1946, the houses were full of families who looked like hers: lower income, Black, two parents with kids. The sidewalks were full of children playing, and the mothers watched over them all from their windows and stoops.

When Leroy Thorpe moved in in the 1980s, the same streets were dense with drug markets. Hundreds of people crowded the streets, day and night, buying and using drugs and hiring prostitutes. Telephone booths were used for drug deals. Gunshots rang out from cars driving by, shooting at rivals.

When John Lucier, an Ohio-born government employee, found a deal on a house in Shaw in 2002, he found himself moving into one of the four occupied homes on a block of seventeen. Every morning, he walked alone to the newly opened metro station, waiting by himself on the empty platform. Census data shows the neighborhood had been emptied out.

When Preetha Iyengar became pregnant with her first child in 2016, she jumped into a sellers market to buy a row house in the area with her husband, losing one bidding war before winning another. As she walks down her block, she sees children playing on the spontaneous playground that emerged next to the pizza place on the corner. During the day, au pairs and nannies push children down the sidewalks, and housecleaners jump in and out of their cars to keep the houses of their wealthy clients looking immaculate.

At this moment, they are all still here, living alongside each other. Black, White and Asian residents talked to me about living in an integrated neighborhood for the first time in their lives. How do they build community in such diversity?

The narrators reflect deeply on their experiences of living alongside those of a different race. How do they experience respect? How do they experience belonging? What happened to Black people in this neighborhood? Im going to give it to you straight, said Leroy Thorpe, a powerful narrator you will first encounter in the 1980s section of this book. I hope you will read through to the end of the book, when he does give it to me straight and joins some of my earliest narrators with reflections about the most beautiful gains and the most painful losses of living in this neighborhood and when some of the most recent newcomers wonder about their responsibilities to their neighbors.

The heart of this book comes from the voices of the narrators. All the narrators in the project are using their real names and have graciously consented to allow me to publish their stories. Im so grateful for their voices, which tell the truth of their experiences and their feelings.