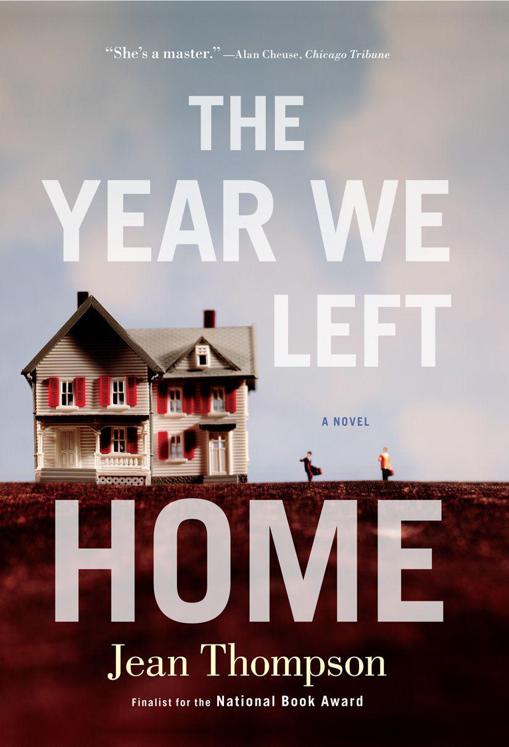

ALSO BY JEAN THOMPSON

N OVELS

City Boy

Wide Blue Yonder

The Woman Driver

My Wisdom

C OLLECTIONS

Do Not Deny Me

Throw Like a Girl

Who Do You Love

Little Face and Other Stories

The Gasoline Wars

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright 2011 by Jean Thompson

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition May 2011

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Designed by Kyoko Watanabe

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thompson, Jean.

The year we left home / Jean Thompson.

p. cm.

1. FamiliesUnited StatesFiction. 2. Brothers and sistersFiction.

3. United StatesSocial life and customs20th centuryFiction.

4. United StatesSocial conditions20th centuryFiction.

5. National characteristics, AmericanFiction. I. Title.

PS3570.H625Y43 2011

813.54dc22

2010047553

ISBN 978-1-4391-7588-0

ISBN 978-1-4391-7591-0 (ebook)

Contents

Iowa

JANUARY 1973

Iowa

APRIL 1975

Seattle

JULY 1976

Iowa

OCTOBER 1979

Iowa

NOVEMBER 1979

Chicago

MARCH 1981

Iowa

APRIL 1983

Reno, Nevada

JUNE 1985

Iowa

JUNE 1989

Iowa

SEPTEMBER 1989

Chicago

JANUARY 1990

Iowa

APRIL 1993

Veracruz, Mexico

OCTOBER 10, 1996

Iowa

APRIL 1997

Italy

JUNE 1998

Iowa

DECEMBER 2000

Iowa

JUNE 2003

To everybody who left home

THE

YEAR

WE

LEFT HOME

Iowa

JANUARY 1973

The bride and groom had two wedding receptions: the first was in the basement of the Lutheran church right after the ceremony, with punch and cake and coffee and pastel mints. This was for those of the brides relatives who were stern about alcohol. The basement was low-ceilinged and smelled of metallic furnace heat. Old ladies wearing corsages sat on folding chairs, while other guests stood and managed their cake plates and plastic forks as best they could. The pastor smiled with professional benevolence. The bride and groom posed for pictures, buoyed by adrenaline and relief. There had been so much promised and prepared, and now everything had finally come to pass.

By five oclock the last of the crowd had retrieved their winter coats and boots from the cloakroom and headed out. It was January, with two weeks of hard-packed snow underfoot and more on the way, and most of them had long drives from Grenada, over country roads to get back home. The second reception was just beginning at the American Legion hall, where there would be a buffet supper, a bar, and a dance band.

The brides younger brother had been sent to open the Legion building so that the food could be brought in ahead of time. He drove his pickup truck the mile from the church, playing the radio loud to shake off the strangeness of the day. Hed been an usher at the wedding and he still wore his dark suit and blue-tinted carnation boutonniere, clothes that made him feel stiff and false. The whole import of the wedding embarrassed him powerfully, though he could not have said why. Many things had been disquieting: his sister in her overdone bridal makeup, his mothers weeping, the particular oppressiveness of anything that took place in church, the archness of the female relatives who told him how tall and handsome he looked. Pretty soon well get to dance at your wedding, hey? Hed shrugged and said, Well, they could at least dance, which had made his girlfriend mad.

She was still back at the church and still mad, which was why hed managed to get away by himself, if only for a few minutes. As he was leaving, shed whispered that he should see what they had in the liquor cabinet over there. He guessed that that was what it was going to take to get her back in any kind of a good mood. A bottle they could show off as a trophy, then drink some night while they were out driving around.

The radio was playing Horse with No Name. He turned it up and sang along:

Ive been through the desert on a horse with no name

It felt good to be out of the rain

He wished he was out there right now, in some desert, instead of smack in the middle of his family, who, because they knew his origins and his history, thought they knew everything about him. He couldnt account for this feeling when a wedding, after all, was supposed to be this big happy thing. He guessed he must be some kind of freak.

The gray afternoon was already shutting down when he pulled into the Legion parking lot, got out, and fumbled with the stiff lock. It gave way and he stepped inside.

The hall was a big bare space with a much-buffed tile floor. Gloomy light reflected from it in pools. To one side was a kitchen with a large stainless steel double sink, two restaurant-style wall ovens, and a pass-through to the main part of the room. Long tables covered with white paper tablecloths were set up to receive food, and stools and hightops were stacked in the foyer. He tried the bar closet but as expected it locked with a separate key. Then he heard another car pull up. He turned on the overhead lights and went back out into the cold.

His Uncle Norm and Aunt Martha were unloading their station wagon. Ryan, his uncle said by way of a greeting, and handed him a foil-covered metal pan. Careful, this ones heavy.

His aunt said it had been a beautiful wedding, hadnt it, and Ryan said it had. That was the extent of the small talk since there was all the food to manage, work to be done, and with Norm and Martha, work came before everything else. There were a dozen or more big pans to carry inside, and two coolers, and a cardboard box full of paper towels and pot holders and other useful items. Just set everything out on the table, Martha directed, hanging up her coat and putting on the apron shed brought from home. Ryan, peeking under the foil, found sliced ham with raisin sauce, a macaroni-and-tomato casserole, a green salad, potatoes topped with shredded orange cheese, beef in gravy, chicken and biscuits, corn pudding. There were sheet cakes too, and bags of dinner rolls.

He guessed that Norm and Martha had organized the supper, collecting the prepared food from different country relatives. It would have been a very Norm-and-Martha thing to do. They were not, technically, his aunt and uncle. They were his grandmothers cousins, his mothers mothers people. Tall, freckled, rawboned, they seemed not to have aged since his childhood. His mother had been a Tesman and her mother was a Peerson, and the Peersons were the scariest of the old Norwegian families. They lived out in the boondocks, what his dad called Jesus Lost His Shoes territory, and their church still held services in Norwegian the third Sunday of every month. Most of them farmed. They believed in backbreaking labor, followed by more labor, and in privation, thrift, cleanliness, and joyless charity. If you wanted a tree taken down or a truck winched out of a ditch or a quarter of a cow packaged for your meat locker, you called a Peerson. If you wanted lighthearted company, you called someone else.

Next page