Copyright Lester K. Little 2014

The right of Lester K. Little to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK

and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

Distributed in the United States exclusively by

Palgrave Macmillan, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York,

NY 10010, USA

Distributed in Canada exclusively by

UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall,

Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data applied for

ISBN 978 0 7190 9522 1 hardback

First published 2014

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset

by Out of House Publishing

Prologue: The setting, the main characters, and two questions

Our story is set in northern Italy within a rectangle of the earths surface that would fit comfortably within the bounds of Kansas but with a range in elevation going from sea level to well over 4,000 m. Five million years ago a quarter or so of it lay under the sea, the lowest parts several hundred metres under. Our story, though, will deal with only a bit over a 10,000th of that period, or about six centuries, and the action will take place mainly between sea level and elevations of up to 1,200 m.

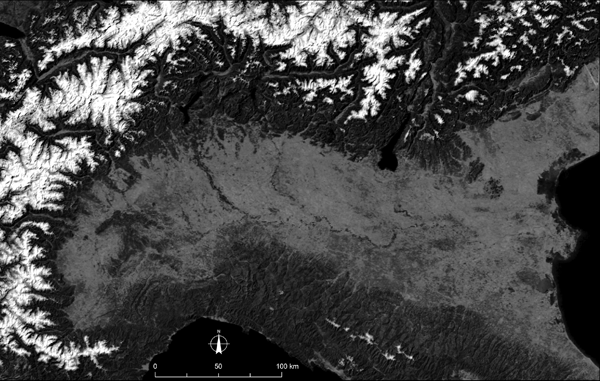

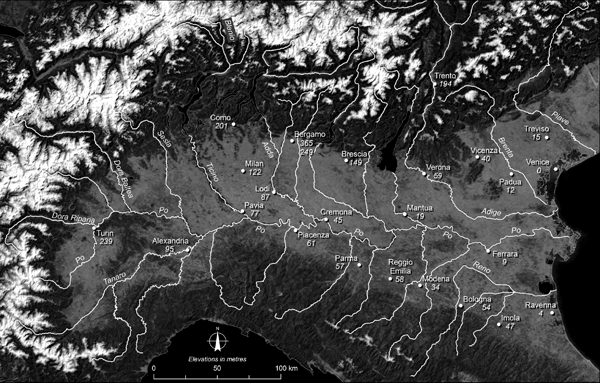

Seen at a glance from outer space, the outstanding features of this setting are clearly the arc of mountains ringing the north, west, and south sides; the flat land in the centre; and the opening out to the sea in the east (see ). Only the Adige on the north side and the Reno on the south, along with the few rivers to their east, empty directly into the Adriatic Sea. After its own descent from the Maritime Alps, the Po passes Turin at a height above sea level of some 239 m; the point where the Ticino coming down from Switzerland joins it near Pavia is at a height of about 77 m. The Po falls to 61 m near Piacenza, 45 m at Cremona, and so on to 9 m as it passes just north of Ferrara and branches out into the broad delta that finally brings it down to sea level. This topography assumes a key role in the story.

Figure 1 Northern Italy seen from outer space. This Nasa satellite image includes more than the area discussed in the text, namely some of the French Alps and nearly half of Switzerland.

Figure 2 Map superimposed on the NASA satellite image showing rivers that flow from the Alps and the Apennines into the Po Valley plain and eventually the Adriatic Sea, plus the cities that fi gure in this study.

Alberto, the leading protagonist, was a wine porter in the city of Cremona, where he lived until his death in 1279. Some said he was from Villa dOgna, others said Bergamo. Although the first claim was correct, the second was not really wrong, given that Villa dOgna is a village up in Bergamos mountainous hinterland.

How and when he went from his birthplace to Cremona we can only guess. The year had to be fairly close to the middle of the 1200s. We are reasonably safe in imagining him, a poor peasant, leaving home and the fields where he has worked since boyhood. He walks past the parish church of Saint-Matteo to the edge of the village, and starts down the road to the valley floor and the river that runs through it. The village is Villa dOgna, a pastoral and agricultural community situated in the orbit of the town of Clusone at an elevation of about 550 m. The river is the Serio, which originates 25 km or so further north, up at nearly 3,000 m in the pre-Alps. He has no reason to go up in that direction. In the winter the whole upper valley is closed off by snow, while in the summer it is mainly shepherds who take their flocks up there to pasture. Instead, Alberto follows the river in its hasty descent of some 300 m and 33 km to where it skirts the eastern edge of the city of Bergamo.

The year is somewhere close to AD 1250, give or take. The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, Wonder of the World, is at the end of his intensely fascinating life, hounded to the last by the fourth of the popes he has known all of them either trained in the law or surrounded by men who were who have striven to build up the papal monarchy at the expense of his empire with their claims to control Rome and much of central and northern Italy. Kublai Khan, at the other end of Eurasia, is about to take supreme command of the Mongols great empire, which stretches from the Pacific Ocean to the Black Sea. Ferdinand III, king of Castile, is completing his conquest reconquista, the Spanish Christians call it of Seville, thereby raising high the bars of both crusading and sainthood for his French counterpart, Louis IX. The new kind of religious orders founded a generation ago by Saints Francis and Dominic have become the vanguard of Latin Christianity at home in Italy, elsewhere in Europe, and in the vast stretches of Mongol territory where Franciscan friars have gone to preach. The Polo brothers, merchants of Venice, will soon be following the route of those friars accompanied by their son and nephew, Marco, to arrive eventually at the court of the Great Khan himself.

Architecture, meanwhile, has been going through one of those rare moments of daring innovation of structural technique, Gothic vaulting in this case, beginning a century ago in a small area centring on Paris and now spreading out from there. Nothing like it has been seen since the introduction of the spherical pendentive in sixth-century Constantinople, an invention that permitted the circular base of a dome to rest upon a square support, or will again before the introduction of the steel-frame skyscraper in late-nineteenth-century Chicago. Similar in audacity to Gothic vaulting are the complex yet coherently organised summaries of knowledge being constructed by scholars: in medicine at Salerno, in law at Bologna, or in theology at Paris.

Villa dOgna knew nothing of these matters. No one there knew or much cared who the Holy Roman emperor was, or the pope either for that matter. No friars preached there, and no long-distance traders passed through. There was no stunning architecture to be seen or holders of academic degrees from Bologna to be found. Stories about Jews and Saracens there may well have been, but the notion that in the wide world beyond their mountains entire peoples existed who were neither adherents to nor opponents of Christianity had not penetrated. Everybody, though, had heard about cities and their peculiar mix of wondrous sights, strange people, lively distractions, and terrifying dangers for both body and soul; besides, word also had it that cities harboured opportunities to earn and even stash away some money.